Achieving tranquility requires steady habits: regular work and reading, doing good for others, limiting unnecessary desires, and learning to endure loss with patience. Over time, these practices build a stable mind that helps individuals pursue happiness with greater clarity, resilience, and balance.

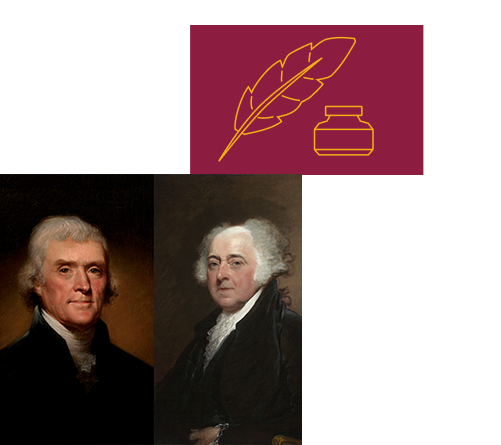

Healing a Founding Friendship

Grounded in History

In this video, you will observe how the long public disagreements between John Adams and Thomas Jefferson gradually give way to a renewed friendship grounded in shared philosophical reflection. Watch for how their letters reveal tranquility not as mere calm, but as a practiced virtue shaped by forgiveness, restraint, daily discipline, and the steady ordering of the passions.

Tranquility as a Virtue in Adams and Jefferson’s Friendship

Focus on how tranquility is introduced as a virtue through the story of Adams and Jefferson’s political rivalry and eventual reconciliation. Think about what challenges their friendship faced and what tranquility might mean in this context.

Adams and Jefferson, once close collaborators, became political rivals after the contentious 1800 election. Their estrangement lasted for years, marked by silence and mutual resentment.

However, with encouragement from Benjamin Rush, the two resumed writing to one another and began a renewed exchange of ideas. In their letters, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson reflected on happiness as life’s goal, virtue as its foundation, and tranquility as a steady state of mind shaped by daily habits, self-control, and honest reflection.

The story of John Adams and Thomas Jefferson reflects the tension between public disagreement and the private discipline of self-government. Though they differed sharply in politics and temperament, their later letters show a shared concern with happiness as the aim of life, virtue as its foundation, and tranquility as the steady ordering of the passions.

Their exchange makes clear that tranquility is not achieved by avoiding conflict, but by practicing moderation, patience, and daily habits of reflection amid real disappointments and losses. Their journey suggests that moral growth requires effort, self-examination, and the ongoing work of governing one’s own emotions.

Tranquility Under Pressure in Later Years

Consider how the ideal of tranquility was tested in the later years of John Adams and Thomas Jefferson. Both men experienced political disappointment, sectional strain over slavery, and the burdens of retirement from public life. Adams endured deep personal losses, including the death of Abigail Adams in 1818, while Jefferson struggled with financial stress and the contradictions within his own legacy. Reflect on how these pressures tested their ability to sustain equilibrium of the passions.

For both, tranquility was not a fleeting mood but a condition achieved through discipline. It required daily habits of reading, exercise, correspondence, benevolence, and the contraction of excessive desire. Their letters show that reflection on grief, patience in disappointment, and attention to present duties were essential to preserving peace of mind.

At the same time, their lives reveal both the limits and the resilience of this virtue. Adams grew skeptical about human perfectibility, and Jefferson placed enduring hope in education and the progress of reason. Yet both maintained that happiness depended upon cultivating inner steadiness despite outward uncertainty. In this way, their exchange demonstrates how tranquility could be pursued, imperfectly but persistently, even amid loss, doubt, and the unfinished American experiment.

Check Your Understanding

The following activities will help you reinforce and assess your understanding of tranquility, reconciliation, and the civic value of healing division. Take a moment to reflect on what you’ve learned before moving forward.

What best describes how Adams and Jefferson viewed tranquility in their later friendship?

Concluding Module 10

Rethinking the Pursuit of Happiness

In this module, we explored how tranquility took shape in the renewed correspondence between John Adams and Thomas Jefferson. Through reflection, moderation of the passions, daily discipline, and charitable exchange, they came to understand tranquility not as simple calm, but as equilibrium of a well-governed mind.

Their letters show that happiness required more than public achievement. It depended on virtuous habits, contraction of excess desire, patience in loss, and the steady practice of self-government. Their lifelong dialogue demonstrates that the pursuit of happiness rests on cultivating inner balance amid disagreement, disappointment, and change.

Key Takeaways

- Tranquility is equilibrium of the passions, a disciplined condition of mind achieved through reflection, moderation, daily industry, and the governance of desire, not merely outward calm.

- The renewed correspondence between John Adams and Thomas Jefferson illustrates how humility, patience, and charitable judgment support both reconciliation and the pursuit of happiness.

- Their letters draw on shared wisdom from classical, Christian, and Enlightenment traditions, emphasizing self-mastery, benevolence, and the steady ordering of the passions as foundations of virtue.

- Political disagreement, grief, disappointment, and public strain test tranquility, requiring ongoing habits of reflection, restraint, and contraction of excess desire.

- For the Founders, happiness was the aim of life, virtue its foundation, and tranquility its condition, cultivated through practiced habits rather than achieved as moral perfection.

Food For Thought

- How can practicing tranquility as a disciplined virtue help us navigate political or personal conflicts in today’s society?

- In what ways might reflection, forgiveness, and restraint contribute to healthier relationships in your own life?

- Considering the Founders’ view of happiness as moral alignment, how might cultivating virtues like tranquility influence your pursuit of a meaningful life?

Optional Reading

- Jeffrey Rosen, The Pursuit of Happiness, Chapter 9

- Jane Kamensky, Jefferson, Adams, and the Crucible of Revolution (opens in a new tab)

- Gordon Wood, Friends Divided: John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, Prologue and Chapter One

Created in partnership with Arizona State University.