Beginning the Journey to Understanding

An introduction to the Founders’ understanding of happiness as a lifelong pursuit of virtue and self-mastery, setting the stage for the ideas and historical figures explored throughout the course.

Happiness Defined Across Time

Drawing on classical and Enlightenment sources, the Founders describe the pursuit of happiness as the triumph of reason over passion, what we would now call emotional intelligence: governing anger, fear, and destructive impulses through conscience and deliberation.

Follow the timeline below to see how the Founders' developed their definition of happiness as living a life of spiritual and moral purpose.

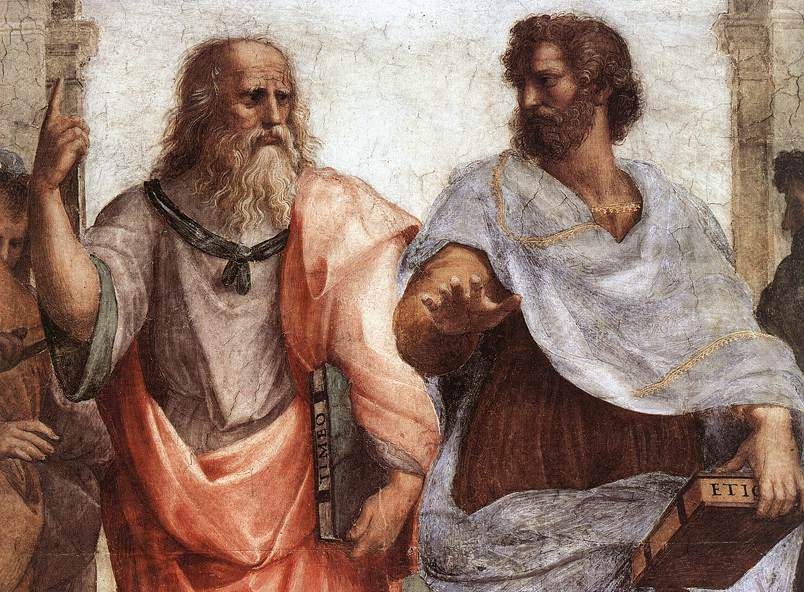

Ancient Greece and Rome

Classical Foundations: Virtue as Happiness

-

Classical Greek and Roman moral philosophers define happiness not as pleasure or emotional satisfaction, but as virtue; a lifelong process of moral formation.

-

They emphasize the triumph of reason over passion, in which individuals discipline destructive emotions such as anger, fear, and excess through conscience and deliberation.

-

This tradition highlights that self-mastery is the foundation of a good life and essential for both personal fulfillment and the health of the political community.

-

The fall of Rome serves as a historical warning that societies collapse when virtue erodes.

17th–18th centuries

Enlightenment Transmission: Virtue and Self-Government

- Enlightenment thinkers' perspectives on moral philosophy heavily influenced America's founders, reinforcing the belief that happiness means being good rather than feeling good.

- During this period, the idea emerges that political self-government requires personal self-government: A free republic can only survive if citizens possess the discipline, restraint, and moral character needed to govern themselves.

- Without civic virtue at the individual level, even the strongest political institutions are put under strain and can falter over time.

1776

The Declaration of Independence: Moral Purpose as a Natural Right

-

The Declaration of Independence identifies “the pursuit of happiness” as an unalienable right, reflecting classical and Enlightenment understandings.

-

This phrase refers to the right and responsibility to pursue a life of moral purpose, self-mastery, and character development, rather than mere pleasure or comfort.

-

Happiness is implicitly tied to citizenship and the common good, as a society committed to liberty depends on individuals committed to virtue.

Late 18th century

The Founders’ Lived Philosophy: Virtue, Citizenship, and the Republic

-

Founders such as Benjamin Franklin, George Washington, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and Alexander Hamilton actively practiced and promoted habits of industry, temperance, moderation, and sincerity.

-

They viewed life as a daily struggle for self-improvement and emotional discipline, understanding happiness as a lifelong pursuit of character excellence.

-

For them, being a good person and being a good citizen were inseparable.

-

A virtuous republic begins with virtuous individuals, and each citizen’s commitment to self-discipline and moral growth is also a commitment to the common good.

-

This philosophy shaped both their personal lives and the foundational ideals of the American experiment.

Happiness as Reason over Passion

Drawing on ancient Greek and Roman philosophy, the Founders believed that happiness depended on the ability to govern oneself. They often described this as a struggle between reason and passion. Not eliminating emotions, but learning how to regulate them. A good life, they believed, required reason to guide emotion so that individuals could curb immediate impulse in order to pursue long-term flourishing.

1. Reason (Logos)

Calm deliberation, self-command, and the ability to choose long-term flourishing over immediate impulse.

Powerful emotions such as anger, fear, and desire that can overwhelm judgment if left unchecked.

This balance between reason and passion was not just a personal ideal. The Founders believed that a constitutional democracy could survive only if citizens learned to govern themselves—cooling passions in favor of thoughtful deliberation.

2. Passion (Pathos)

Powerful emotions such as anger, fear, and desire that can overwhelm judgment if left unchecked.

This balance between reason and passion was not just a personal ideal. The Founders believed that a constitutional democracy could survive only if citizens learned to govern themselves—cooling passions in favor of thoughtful deliberation.

Knowledge Check

Sort each example based on whether it reflects reason or passion as the Founders understood them.

Concluding Lesson 1

Rethinking the Pursuit of Happiness

Drawing on classical philosophy and Enlightenment moral thought, the Founders believed that happiness emerged from the steady cultivation of virtue, the discipline of reason over unproductive passions, and a commitment to continual learning and self-improvement. This vision linked private character to public freedom: self-government in a constitutional democracy required citizens capable of governing themselves. The pursuit of happiness, then, was not a destination but a practice, one rooted in daily habits, moral reflection, and service to the common good.

Key Takeaways

-

For the Founders, happiness meant being good, not merely feeling good, and was grounded in virtue rather than pleasure.

-

Classical thinkers taught—and the Founders agreed—that reason must guide passion. Emotion was not to be eliminated, but disciplined toward productive ends.

-

Personal moral development and civic responsibility were inseparable: good citizens must first practice self-mastery.

-

The pursuit of happiness was understood as a lifelong commitment to learning, reflection, and character improvement, not moral perfection.

-

Even the Founders recognized their own failures and contradictions, yet believed that continual striving toward virtue still mattered.

Food For Thought

- If true happiness depends on character rather than comfort, how might that change the way we structure our daily habits and priorities?

- In a modern democracy, what forms of personal self-government are most necessary to sustain political freedom today?

Want to Learn More?

The ideas introduced in this module have inspired centuries of debate and reflection. If you’d like to explore them further, the resources below offer additional perspectives on what the Founders meant by the pursuit of happiness—and why the phrase continues to resonate today.

This material is optional and intended for learners who want to go deeper.

Optional Reading

- Benjamin Franklin, Autobiography, Part II(opens in a new tab)

- Gordon Wood, The Creation of the American Republic, Chapter 1

Created in partnership with Arizona State University.