On Election Day, an old topic will get new life when political pundits discuss the chance of a deadlocked presidential contest between President Donald Trump and Joe Biden. That did happen once in American history, and the Founders crafted an amendment to greatly lessen the effects of another tie. But things did not quite work out as planned.

Initially, the Constitution written in Philadelphia in September 1787 and ratified in June 1788 used a different system for electing a president and vice president. The Electoral College, in conjunction with Congress, would choose the winners of the presidential election. Under Article 1, Section 1, the state legislatures would select electors to cast votes sent to Congress to certify. Some states used popular voting to pick electors, while others turned to state legislatures to choose electors. Each elector voted for two candidates. The person with the most votes certified by Congress became president. The second-place candidate was vice president.

Initially, the Constitution written in Philadelphia in September 1787 and ratified in June 1788 used a different system for electing a president and vice president. The Electoral College, in conjunction with Congress, would choose the winners of the presidential election. Under Article 1, Section 1, the state legislatures would select electors to cast votes sent to Congress to certify. Some states used popular voting to pick electors, while others turned to state legislatures to choose electors. Each elector voted for two candidates. The person with the most votes certified by Congress became president. The second-place candidate was vice president.

That system worked when George Washington was the overwhelming choice in the first two presidential elections. But in 1796, Washington declined a third term in office and rivals John Adams and Thomas Jefferson fought bitterly to replace Washington. Adams won the election, but Jefferson became the vice president. It was not an ideal arrangement since the same two candidates would face off in the 1800 election.

The original presidential election system broke down in 1800, when Jefferson and his running mate, Aaron Burr, tied for first place, but they did not have a majority of the electoral college votes. The tie moved the election to the House of Representatives to decide, which was controlled by the losing party, the Federalists. Burr did not discourage the Federalists for voting for him in the run-off election, which lasted for 36 ballots in the House. In the end, Jefferson became president and Burr, his rival, was vice president.

In response, Congress proposed the 12th Amendment, which was ratified before the 1804 election. The Amendment made clear that electors had to cast separate votes for the president and the vice president. If a candidate did not get a majority of electoral votes after the results were certified in Congress, the House would choose the new president, and the Senate would elect a new vice president.

The 12th Amendment did not eliminate the chances of a tied presidential election, but it made the process of picking a winner in Congress a much cleaner one. “Never again could presidential candidates and their running mates face the embarrassing kind of tie vote that forced the House to choose between Jefferson and Burr,” said scholar Sanford Levinson, in the National Constitution Center’s Interactive Constitution essay on the subject.

Since 1804, Congress had decided two elections where no candidate had the majority of electoral votes: the 1824 presidential election and the 1836 vice-presidential election. In the 1824 election, Andrew Jackson had the most popular votes, but not a majority. The House chose John Quincy Adams in the contingent election instead of Jackson. In the 1836 election, Virginia shunned Martin Van Buren’s running mate, Richard Mentor Johnson, giving its votes to another vice presidential candidate. The Senate, however, voted for Johnson in the run-off election.

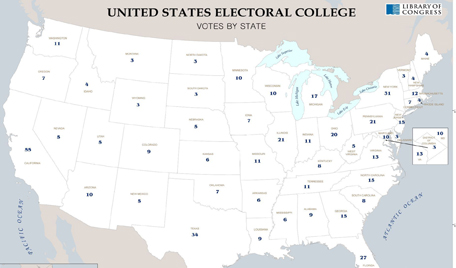

Congress has not been faced with a tied presidential or vice-presidential election since 1800. However, the 23rd Amendment’s ratification in 1961 increased the chance of a tied election as a simple matter of mathematics. Before 1961, the total number of electors in the presidential election had been an odd number since 1904. The addition of electoral votes for the District of Columbia because of the 23rd Amendment made the electoral college total an equally divisible number: 538 electors. In the modern major two-party system, a dead-heat 269-269 electoral college vote was now possible, assuming all electoral votes were cast and then certified by Congress.

To be sure, there are other scenarios that could prevent one candidate from having a majority of electoral college votes, such as a third-party candidate winning electoral votes, or a state allowing vote-switching by a faithless elector. The Supreme Court’s July 2020 unanimous decision in Chiafalo v. Washington gave states more tools to combat faithless electors. “A State may enforce an elector’s pledge to support his party’s nominee—and the state voters’ choice—for President,” said Justice Elena Kagan writing for the full court.

In the 2020 election between Donald Trump and Joe Biden, there are a few scenarios for a tied election with 538 electoral votes in play. For example, if President Trump retains his southern and lower Midwest state support from 2016, loses Pennsylvania, and wins Arizona and Wisconsin, his electoral total is 269 votes - if he also takes one electoral vote in Maine or Nebraska (which allocate votes by congressional districts). Another scenario has PresidentTrump retaining his most of his 2016 support, winning Pennsylvania and taking two electoral votes in Maine and Nebraska while losing Arizona and Nevada. That also comes to 269 electoral votes - and a tied election.

If the election remains tied after expected legal challenges and the submission of certified results from the states to Congress, the newly elected House would decide the presidential winner in January 2021 based on a vote of state delegations and not individual representatives. Currently, the Republicans control 26 of the 50 House delegations that would vote in a contingent election for president. The Senate would vote to pick the vice president based on a majority of members casting votes.

The Congressional Research Service issued updated guidance on all the twists and turns of a contingent election in October. The constitutional process does allow for the possibility of the president and vice president chosen in the contingent election to be from different political parties. That rival vice president would also serve as the Senate’s tie-breaking vote after the new president is inaugurated.

While unlikely, these scenarios would present the nation with a conflict between a president and vice president, a situation which in part contributed to Founders’ motivation behind the 12th Amendment.

For more information, websites such as 270towin.com and others allow users to pick different electoral college scenarios.

Scott Bomboy is the editor in chief of the National Constitution Center.

For more Electoral College resources:

Blog Posts

The Constitution and contested presidential elections

Podcasts

Election 2020 in the Courts

Town Hall Videos

America’s Contentious Presidential Elections: A History

Educational Videos

Learning About the Electoral College With Tara Ross (High School/College Session)