One of the little-understood provisions of the 12th Amendment allows the U.S. Senate to name a Vice President under very limited circumstances. It happened once, on this day in 1837.

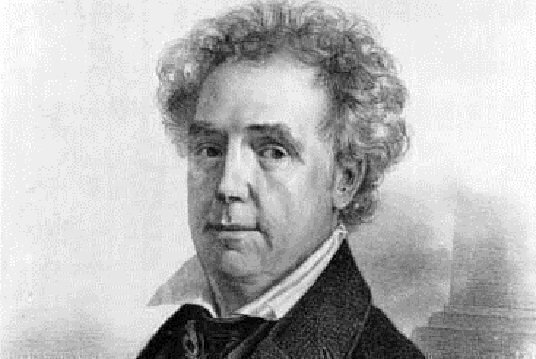

In the 1836 presidential election, Martin Van Buren won the election with 170 electoral votes, defeating William Henry Harrison and three other candidates. Van Buren and his running mate, Richard Mentor Johnson, were hand-picked by outgoing President Andrew Jackson to continue his policies.

Van Buren was a master politician, who help to create the new party system. He also was able to navigate his way through a tough election. Johnson had been a controversial figure for several reasons, but Jackson and others thought the Kentucky native would balance the ticket.

Instead, Virginia rejected Johnson and the state’s 23 vice-presidential electoral votes went to William Smith of Alabama, in a case of unfaithful electors rejecting an elected candidate. Johnson needed 148 votes to become Vice President in the election; instead, he received 147 votes, falling one vote short.

The vice-presidential candidate was dogged by claims during the 1836 campaign of a more scandalous nature, at least in the South. After Johnson’s father died, he inherited a slave, Julia Chinn, who was an octoroon. Chinn became Johnson’s common-law wife, since the couple couldn’t marry under miscegenation laws in effect, and they had two children before Chinn died in 1833. Johnson then had two other relationships with women who were black or mixed race.

On February 8, 1837, the Senate convened under the terms of the 12th Amendment under the following provision: “The person having the greatest number of votes as Vice-President, shall be the Vice-President, if such number be a majority of the whole number of Electors appointed, and if no person have a majority, then from the two highest numbers on the list, the Senate shall choose the Vice-President.”

The candidates were Johnson, and Harrison’s running mate, Frances Granger of New York. Johnson won the contingent vote, 33-17, on party lines, and became the ninth Vice President.

Johnson’s four years as Vice President were marked by an unusually high number of tie-breaking votes required in his role as president of the Senate. But Johnson also frequently went home to manage his tavern in Kentucky.

Van Buren decided to run for re-election in 1840 with no vice-presidential running mate after his experience with Johnson. But Johnson campaigned for re-election on his own and received 48 electoral votes for Vice President, compared with Van Buren’s 60. Harrison and his vice-presidential candidate John Tyler received 234 electoral votes to win the election easily.

After leaving Washington, Johnson spent a decade trying to continue his political career, until he died at the age of 70 in Kentucky in 1850.