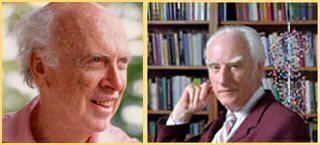

Dr. James D. Watson & Dr. Francis Crick

The 2025 Liberty Medal

The National Constitution Center has honored Hamilton and Ron Chernow for their singular impact in bringing the story of the U.S. Constitution to life for generations of Americans and inspiring a deeper public engagement with the principles of the founding era.

"In the 20th century, the extraordinary record of the natural sciences and the technologies that they inspired is one of the grand achievements of human liberty. Watson and Crick and their work on DNA are symbols of the tremendous impact of science on our lives and welfare and on public policy…(This work) demonstrates the importance of enlightened scientific progress and."

"In the 20th century, the extraordinary record of the natural sciences and the technologies that they inspired is one of the grand achievements of human liberty. Watson and Crick and their work on DNA are symbols of the tremendous impact of science on our lives and welfare and on public policy…(This work) demonstrates the importance of enlightened scientific progress and." Liberty Medal International Selection Commission

Dr. James D. Watson

July 4, 2000

Independence Hall

Philadelphia, PA

The Pursuit of Happiness

We have assembled here this Independence Day to reaffirm that freedom is at the heart of human existence. When in control of our individual destinies, we thrive and look forward to the future. In contrast, when our aims and actions are determined by others, we feel stifled and unable to live up to our potentials as human beings. Without life, liberty and the ability to pursue happiness, human beings have no chance to realize the great talents that let Galileo see the moons of Jupiter, or Rembrandt catch the essence of humanity in his portrayal of our faces.

In preparing our country for the war that would soon envelop us, Franklin Roosevelt spoke of four essential freedoms -- freedom of speech, freedom of religion, freedom of want, and freedom from fear. That bleak January 1941 day, Roosevelt emphasized freedom from fear, knowing well the mortal potential that attainment of Hitler's ugly aspirations held for human life. But if Thomas Jefferson were then mobilizing our nation, he would have added a fifth freedom -- freedom from ignorance. The uneducated man can never be in control of his destiny. Had newspapers, the BBC, and cinema newsreels not informed the general public that Hitler was evil incarnate, the fateful Battle of Britain might very well had a different outcome.

As a product of the 18th century intellectual enlightenment, Jefferson saw truth arising from observations and experiments. So he wanted his state of Virginia to select, for special educational enrichment, youths of inherent genius who were sprinkled as liberally among the poor as the rich. He saw the knowledge so learned as the ultimate safeguard of liberty. Correspondingly tyrannies thrive when education is prevented. Cromwell's victorious march across Ireland was soon followed by abolition of education for its Catholic denizens.

Essentially a deist who saw a role for God only in the creation of the universe and its life forms, but not in events afterward, Jefferson did not see organized religions as the basis for moral virtue. Instead he accepted the idea going back to the Greeks of natural rights which arose out of the essence of the human being as created by God. To Jefferson it was self evident that all humans were created equal with inalienable rights that transcended where or in what period of history one was living.

Today, 224 years after Jefferson so eloquently expressed these ideas in the Declaration of Independence, biology is witnessing the completion of an intellectual renaissance that Charles Darwin began in the nineteenth century. Through his Theory of Evolution through Natural Selection, Darwin forever changed our view of human life. He saw ourselves as the products not of creation by a God as revealed in Genesis but as arising through a series of evolutionary events going back to a common ancestor of many eons ago.

Much more recently we have learned that the variation upon which natural selection acts reflects mutational changes in DNA, the molecule of heredity. Differences between different forms of life reflect differences in the sequences of the four letters -- A, T, G, and C -- of the DNA alphabet. When the double helix was first revealed in 1953, neither Francis Crick nor I ever thought that, within our lifetimes, the three billion letters that compose the human genetic message would ever be close to being deciphered. But just a week ago, elegant technology and innovative science, combined with much human perseverance, allowed the world of science to give to humanity this true book of human life. Already we can see the outline of some 40,000 genes, the discrete packets of DNA information that are used to determine the structure of proteins, the actors in cellular life.

The inborn equality of all humans that Jefferson so forcefully believed in, we now see arising from our common ancestor that existed in Southern Africa only some 100,000 years ago. Most likely the hunter-gatherer Bushmen of the Kalahari Desert are a direct and largely unchanged representation of human life as it then existed. On a recent trip to Botswana, I was struck by the Bushmen's quickness to learn despite speaking a language that only counts "one, two, three, and many." Underlying the close resemblance of all humans to each other is the close similarity of our books of DNA instructions. Individual variations in our DNA sequences amount to less than one letter in 1000 with most of these differences arising long before modern humans spread across Africa into the Middle East.

Modern biological thought, however, is much less compatible with Jefferson's concept of undeniable rights. Evolution has not endowed ourselves or the fox or the chicken for that matter, with the right to live or to be treated well. Instead, every successful animal form has evolved with its own individual needs, say for specific foods. In turn, we all have evolved capabilities that largely satisfy such needs. High among the needs for virtually all vertebrates is liberty; for being free to move and act unimpeded by others is an indispensable condition for evolutionary survival. At the same time, our various brains have been programmed by our genes to initiate actions that keep us alive. Animals that do not seek out food or evade fast moving objects will not likely give rise to offspring.

Jefferson's most unique insight with regard to freedom was his identification of the pursuit of happiness as a fundamental prerequisite for human advancement. Under normal circumstances, most individuals are only fleetingly happy, say, after we have solved a problem, either intellectual or personal, that then lets our brain rest for a bit. Equally important, happy moods also reward higher animals after they make behavioral decisions that increase their survivability. Successfully replenishing fat cells not only turns off appetites but leads to the appearance of pleasure-bringing natural opiates -- the endorphins. A desire for more endorphin-enriched moments may well be the primary motivation for ourselves to seek out food or to bask in Vitamin D-producing sunshine. Likewise, the happiness we feel upon strenuous exercise should be seen as a Pavlovian reward for the physical exertion needed for food gathering and sexual satisfaction.

These moments of pleasure best be short-lived. Too much contentment necessarily leads to indolence. As Shakespeare has Julius Caesar say, "Let me have men about me that are fat and sleek-headed, and such as sleep o' nights. Cassius has a lean and hungry look; he thinks too much; such men are dangerous." But it is discontent with the present that leads clever minds to extend the frontiers of human imagination. During a low moment in World War II, Joseph Stalin wanted to eliminate one of Russia's most brilliant individuals, the theoretical physicist Lev Laudau. Fortunately, one of his colleagues, Peter Kapitsa, saved his life by arguing successfully that Landau was not subversive, only unpleasant.

Every successful society must possess citizens gnawing at its innards and threatening conventional wisdom -- individuals like Thomas Jefferson, Tom Paine and Benjamin Franklin. Without the changes that radical ideas and actions like theirs bring about, established orders go stale and crumble before brasher peoples accepting the new. Now, more than ever, successful nations must be free societies where diversity of thought is not only tolerated but seen as the intelligent response to a constantly changing world. As long as we can see happiness ahead, the worries and faults of today are bearable. So in the perfect world we want some day to exist, humans will be born free and die almost happy.

Dr. Francis Crick

July 4, 2000

Greetings from Southern California!

I am very honored to receive, with Jim Watson, the award of the prestigious Liberty Medal. We are being recognized because in 1953 we put forward the double-helical model of DNA, using the x-ray data of Rosalind Franklin, Maurice Wilkins and their collaborators.

Many people now know that DNA is a double helix but the key feature of the structure is the pairing of the bases. The base A, on one strand, pairs with the base T on the other. In a similar way, G pairs with C. The number plate on my car reads “AT GC” and I find that, even now, many people don’t know what it signifies. If they ask me, I tell them: “That’s the secret of life!”

Thus genes are written in a four-letter language (A, T, G and C) and the genetic information is conveyed by the exact sequence of these bases on any bit of DNA, just as the meaning of an English sentence depends on the exact sequences of its letters.

Since that time there have been major advances. Molecular biologists have learned how to copy any piece of DNA, to cut it in special places and to join pieces of DNA together. They do not usually use ordinary chemical reactions, but instead the tools Nature uses to do these jobs. These proteins—these enzymes—act more quickly, more accurately and more selectivity than smaller chemicals.

With the polymerase chain reaction we can copy again and again any particular piece of DNA, so that from a few molecules of it in a test tube we can synthesize many millions of identical ones.

In addition, scientists have devised rapid methods of sequencing any particular stretch of DNA. More recently, robots have been invented to do this automatically.

The powerful methods now available have made it possible to sequence, almost completely, the entire genetic material—the entire genome—of a number of organisms. Not merely those of various viruses and bacteria (which are relatively small) but already those of a yeast, a nematode and a fruit fly, which are considerably bigger. Before long we expect to have most of the sequence of the human genome (which is bigger still) and after that the sequence of the mouse genome and, eventually, that of many other animals. Nor have plants been neglected. A preliminary sequence of rice has already been announced and that of other plants will soon follow.

The extent and speed of these advances are truly remarkable. Few people, a generation ago, would have guessed that so much would have been achieved by now.

The enormous flood of precise information is going to transform biology and medicine completely, but it is important to realize that it is only a beginning. Most genes code for some particular protein—proteins are the machine tools of the cell. We can translate the base sequence of any such gene into the corresponding one-dimension sequence of amino acids which make up the polypeptide chain of a particular protein. But this polypeptide chain needs to fold itself up to form the correct three-dimensional structure of the protein. For some proteins the 3-D structure has been found by x-ray analysis, but as yet, it is difficult for us to predict the correct three-dimensional shape from the one-dimensional sequence and it is the 3-D shape that matters. We can sometimes make a good guess as to how a particular gene product might act—whether it breaks down a particular small molecule, for example, or whether it acts as a channel in a cell membrane, and so on—but the true function of each gene product will have to be established for each particular gene. As we may have as many as 50,000 different genes—this number is, at the moment, only a very rough estimate—it is going to take some time to find out what each gene does.

After that the next job will be to discover how fast each gene acts and exactly what controls these rates. This rate, of course, is different in different parts of your body. Muscles need the activity of genes making muscle proteins; nerves need genes making nerve proteins, and so on. The rate at which genes act involves feedback processes. Such systems are called “non-linear dynamic systems.” Not much is yet known about these theoretically and they are not easy to study experimentally.

The details of all this are not important. What is important is to grasp that we see before us vast new regions of biology to explore; that we are only just beginning this exploration; and that it will take many scientists, worldwide, many, many years of hard work before we can begin to understand exactly how our bodies and our brains work, how they developed in the womb, and how they evolved since life began on earth several billion years ago.

What impact will all these discoveries make on ordinary people? Even branches of biology such as ecology and environment studies will be altered, but the main impact is likely to be on medicine and agriculture. And they will affect not only the developed countries but also the developing ones.

Already these new techniques have given us some insight into the causes of cancer, and also of diseases such as Huntington’s and early-onset Alzheimer’s. They are helping us to understand and combat AIDS and other infections. New pest-resistant crops have been produced which could help agriculture, especially Third World agriculture. Several domestic animals have already been cloned.

DNA can be used to establish paternity, both for people and for chimpanzees in the wild. It has also shown that a disconcerting number of condemned criminals are in fact innocent. So far, efforts to alter people’s genes for medical reasons have been disappointing, but there have been one or two successes.

Jim Watson has agreed that he will discuss some of the possible future developments in greater detail, and also touch on the many ethical and legal problems that they are likely to produce. It is impossible to predict the future in detail but it is sometimes possible to see general trends. One can only hope that, on balance, all this work will produce more good than evil. In particular, that it will increase freedom from deprivation, one of the freedoms delineated in the concept of freedom associated with The Liberty Medal.

Thank you again for this honor.