The recent seizure and arrest of Venezuelan president Nicolas Maduro and his wife, Celia Flores, on drug-related charges by United States forces is drawing comparisons to a case from an earlier era: Panamanian dictator Manuel Noriega’s arrest and trial 26 years ago.

On Jan. 3, 2026, United States military forces seized Maduro and Flores in Caracas during a covert operation ordered by President Donald Trump; on Jan. 3, 1990, Noriega surrendered to U.S. troops who had surrounded the Vatican embassy in Panama City during an invasion ordered by President George H.W. Bush. Both Maduro and Noriega faced grand jury indictments on drug trafficking charges when they were taken into custody and sent back to the United States for prosecution.

On Jan. 3, 2026, United States military forces seized Maduro and Flores in Caracas during a covert operation ordered by President Donald Trump; on Jan. 3, 1990, Noriega surrendered to U.S. troops who had surrounded the Vatican embassy in Panama City during an invasion ordered by President George H.W. Bush. Both Maduro and Noriega faced grand jury indictments on drug trafficking charges when they were taken into custody and sent back to the United States for prosecution.

Noriega’s subsequent trial in the United States, and the appeals process in United States v. Noriega, may echo several claims that could be advanced in the Maduro case involving extradition powers, sovereign immunity, the Fifth Amendment, and prisoner of war rights. The decisions in the Noriega case also reinforced prior Supreme Court precedents about the ability of a person to face a trial domestically no matter what circumstances led to their return to the United States.

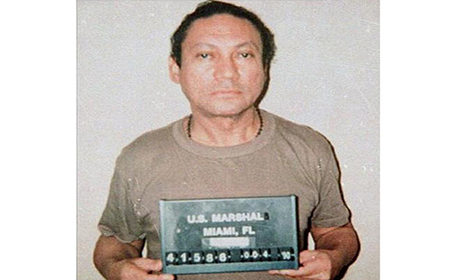

Noriega Detained for Trial

During the 1980s, Manuel Antonio Noriega was the de facto leader of Panama as commander of the Panamanian Defense Forces; it was later revealed that Noriega was on the payroll of the Central Intelligence Agency, and he also worked with a Columbian drug cartel. In February 1988, a federal grand jury in Florida indicted Noriega on drug trafficking charges. Panama's president, Eric Arturo Delvalle, then fired Noriega from his military post, but Noriega refused to leave and Panama's legislature removed Delvalle. The United States considered Delvalle as the constitutional leader of Panama, and after a disputed presidential election, it recognized Guillermo Endara as Panama's legitimate head of state.

On Dec. 15, 1989, Noriega said he was declaring a “state of war” against the United States, and shortly after, President Bush sent United States forces into Panama to protect Americans living there after a U.S. Marine was killed by Panamanian forces at a road block. Bush also said action was needed to ensure the Panama Canal remained open, and to seize Noriega for extradition to the United States to face trial on drug charges.

In June 1990, District Judge William M. Hoeveler ruled against several motions from Noriega’s attorneys claiming that the United States lacked jurisdiction to put Noriega on trial in Miami. “This is the first time that a leader or de facto leader of a sovereign nation has been forcibly brought to the United States to face criminal charges. The fact that General Noriega's apprehension occurred in the course of a military action only further underscores the complexity of the issues involved,” Hoeveler noted. Among Noriega’s additional claims were the precedent of sovereign immunity and his status as a prisoner of war under the Geneva Convention barred his prosecution in the case.

Citing numerous other precedents, Hoeveler said the United States had jurisdiction to try Noriega for acts taken outside of its borders as a matter of international law and statutory construction. “The United States has long possessed the ability to attach criminal consequences to acts occurring outside this country which produce effects within the United States,” he concluded. Hoeveler traced the theory of extraterritorial jurisdiction to Strassheim v. Daily (1911), where Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes determined that acts done by a person “outside a jurisdiction, but intended to produce or producing effects within it, justify a State in punishing the cause of the harm as if he had been present at the effect, if the State should succeed in getting him within its power.”

Hoeveler next considered the question of Noriega’s immunity from prosecution based on his head of state status, the act of state doctrine, and diplomatic immunity. “Noriega has never been recognized as Panama's Head of State either under the Panamanian Constitution or by the United States,” he said. The judge rejected Noriega’s claims that as the de facto ruler of Panama, his actions constitute acts of state, and he found the government of Panama never requested that Noriega be accredited as a diplomat and the United States at no time granted Noriega diplomatic status. Hoeveler also ruled that the government should treat Noriega as if he were a prisoner of war without deciding the question for now.

The court also rejected a Fifth Amendment Due Process argument made by Noriega’s attorneys that Noriega’s presence was illegally secured by United States military forces. Hoeveler cited the Supreme Court’s Ker-Frisbie Doctrine that holds that a court is not deprived of jurisdiction to try a defendant on the ground that the defendant's presence before the court was procured by unlawful means.

Noriega’s Trial and Appeals

Noriega faced a seven-month jury trial in a federal district court in Miami that started in September 1991. During the trial presided over by Hoeveler, the government treated Noriega as if he were a prisoner of war under the Geneva convention and Noriega was permitted to wear his uniform in public during the trial. (His prisoner of war status was later confirmed in a 1992 court ruling from Hoeveler.)

In April 1992, Noriega was convicted on eight counts by the jury, and he was sentenced to consecutive imprisonment terms of 20, 15, and five years. Noriega appealed the convictions to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit.

A three-judge panel from the Eleventh Circuit upheld Hoeveler’s rulings and the jury verdict in 1997. Noriega’s attorneys claimed Hoeveler should have dismissed the indictment due to Noriega’s status as a head of state and the way in which the United States brought him to justice. They believed Noriega also deserved a new trial because of newly discovered evidence.

The appeals court determined Noriega fell short on the head of state immunity claim due to several Supreme Court precedents that deferred such immunity decisions to the executive branch. “By pursuing Noriega's capture and this prosecution, the Executive Branch has manifested its clear sentiment that Noriega should be denied head-of-state immunity,” it said.

The appeals court then rejected claims made by Noriega that existing treaties prevented his extradition of the United States. The appeals court also held the Ker-Frisbie Doctrine defeated Noriega’s Fifth Amendment claims that he was illegally taken to the United States.

With his appeals exhausted, Noriega served 17 years in prison in the United States. He was then extradited to France and to Panama, where he died at the age of 83 in 2017.

Scott Bomboy is editor in chief of the National Constiution Center.