Ted Cruz and other senators are requesting a special electoral commission to investigate the fairness of votes in the 2020 presidential race, harking back to the only time such a body convened. Here is a look at how the Electoral Commission of 1877 was created, in a much different era, to settle a presidential election.

The 1876 presidential campaign between Samuel Tilden, the Democratic Party nominee, and Rutherford B. Hayes, the Republican candidate, was hard-fought. After Election Day on November 7, 1876, Tilden was one electoral vote short of winning the election and well ahead in the popular vote.

The 1876 presidential campaign between Samuel Tilden, the Democratic Party nominee, and Rutherford B. Hayes, the Republican candidate, was hard-fought. After Election Day on November 7, 1876, Tilden was one electoral vote short of winning the election and well ahead in the popular vote.

However, four states—Florida, Louisiana, South Carolina, and Oregon—had problems with their slates of electoral votes, which were yet to be included in the results. In the three southern states, there were legal actions taken after Republican-controlled canvassing boards disqualified Democratic voters.

In Florida, the state canvassing board threw out about 2,000 votes, leaving Hayes with a lead of 924 votes. The Democrats convened their own electoral college vote, sent a second Florida election certificate to Congress signed by the state attorney general, and sued the Republicans in state court. Similar conflicts arose in South Carolina and Louisiana.

In Oregon, its governor, La Fayette Grover, wanted to disqualify a Republican electoral college member, John W. Watts. Grover believed Watts’ appointment as an assistant postmaster conflicted with Article II, Section 1 of the Constitution that required that no “Person holding an Office of Trust or Profit under the United States shall be appointed an Elector.” Grover wanted a Democrat to replace Watts, which would give the presidential election to Tilden. The three southern states represented 19 electoral votes. If they were counted for Hayes, along with Oregon’s contested vote, then Hayes won the election.

Congress faced a clear conflict considering the electoral votes from those four states since it had received multiple slates of electors from each state signed by state officials. Under the Constitution, Congress had an obligation to count all the electoral votes, but no mechanism to decide between competing votes sent from states. As tempers flared, there was also a clear danger of public violence, with calls from Tilden supporters to mobilize the National Guard and the Republicans to use federal troops to keep the peace.

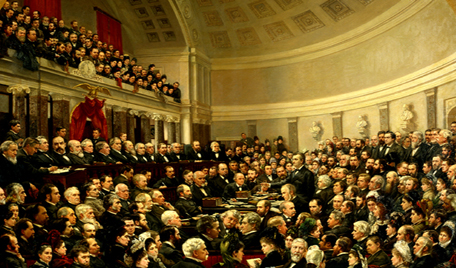

On January 29, 1877, Congress passed and President Grant signed the Electoral Commission Act to break the impasse. The House and Senate named five members each to serve on the commission, and the Supreme Court named five associate justices to serve. The commission would decide “the true and lawful electoral vote of such State” if a state sent multiple electoral slates to Congress. The key vote would fall to one of the named justices, Justice David Davis, an independent. However, Davis decided to accept a Senate seat in Illinois. His replacement, Justice Joseph Bradley, was a Republican.

The commission met on February 1, 1877, to settle the dispute in Florida, which had sent three certificates to Congress. After extensive arguments, the commission ruled on February 9, 1877, in an 8-7 vote in favor of Hayes, with Justice Bradley joining the Republicans. On February 12, 1887, the commission took up the question of Louisiana, which also sent three certificates to Congress. Five days later, the commission decided for Hayes in Louisiana.

The crucial question of Oregon was next for the commission on February 21, 1877, with objections raised about Watts’ position as a postmaster on the day electoral votes were counted in Oregon. In a 1969 academic paper, Philip W. Kennedy described the critical question at stake. “The central issue was whether the commission had the authority to investigate electoral returns,” Kennedy said, or in other words, “go behind” the Democrats’ electoral certificate to investigate wrongdoing (including an alleged bribe paid by the Tilden campaign).

On February 23, 1877, the commission heard that one of its members, Democratic senator Alan G. Thurman, was too ill to vote on the Oregon matter. Instead, the commission moved the vote to Thurman’s house. A unanimous commission rejected a rival Oregon slate with three Democrats submitted to Congress, and it then approved Watts as Oregon’s third elector in an 8-7 vote. The majority said Watts’ position of postmaster was immaterial, since he resigned after the election, resigned as an elector, and then was reappointed as elector before he cast his electoral vote.

The South Carolina dispute also went in favor of the Republicans on February 27, 1877, leaving about a week for Congress to handle the final matter of the presidential election. The Democrats threatened to filibuster and delay proceedings as a protest about the election results. Violence was again possible among the Tilden supporters. That week, members of both parties’ leadership reportedly met at Washington’s Wormley Hotel to finalize an agreement. The Southern Democrats would accept Hayes as president and Republicans would agree to effectively end Reconstruction by removing federal troops from the South, along with other concessions.

On March 2, 1877, at 4:11 a.m., a joint session of Congress declared Rutherford B. Hayes as the next president of the United States. During deliberations that started the previous day, House Speaker Samuel Randall, a Tilden supporter, defeated filibuster efforts from his fellow Democrats. At one point during vocal protests on the House floor, Randall admonished the protesting Democrats. “If gentlemen forget themselves, it is the duty of the Chair to remind them that they are members of the American Congress,” Randall said.

Chief Justice Morrison Waite swore in Hayes the next day in private at the White House, since inauguration day fell on a Sunday that year. The public inauguration was on March 5, 1877. Tilden’s supporters called Hayes “Rutherfraud” after the election, but Tilden had accepted the election results.

A decade later, Congress passed the Electoral Count Act of 1887 to deal with some of the open questions faced by the Electoral Commission. There were still concerns about the Electoral Commission’s inclusion of the Supreme Court justices as election arbiters. The Electoral Count Act of 1887 left the decision solely in the hands of Congress.

The 1887 act’s wordy language provides for methods of handling competing slate electors without needing to convene another Electoral Commission. The act also defines a process about objections to electoral votes in the joint meeting of Congress to tally electoral votes and confirm a presidential election.

While some modern scholars question the clarity of the Electoral Count Act of 1887, it has remained in place as a detailed response to the 1876 presidential election, one of the greatest constitutional challenges faced by Congress in its history.

Senator John J. Ingalls voiced the frustration of many during the debates over the Electoral Count Act of 1887. “The Electoral Commission of 1877 was a contrivance that will never be repeated in our politics. It was a device that was favored by each party in the belief that it would cheat the other, and it resulted, as I once before said, in defrauding both.”

Scott Bomboy is the editor in chief of the National Constitution Center.

For More Information

Kennedy, Philip W. "Oregon and the Disputed Election of 1876." The Pacific Northwest Quarterly 60, 3 (1969): 135-44. Accessed January 3, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40488623.

Haworth, Paul Leland. The Hayes-Tilden disputed presidential election of 1876. Cleveland: The Burrows Brothers Company, 1906.

Shofner, Jerrell H. "Florida Courts and the Disputed Election of 1876." The Florida Historical Quarterly 48, no. 1 (1969): 26-46. Accessed January 3, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30145747.

United States. Electoral Commission (1877)., United States. Congress 1876-1877). (1877). Proceedings of the Electoral Commission appointed under the act of Congress approved January 29, 1877: entitled "An act to provide for and regulate the counting of votes for President and Vice-President, and the decisions of questions arising thereon, for the term commencing March 4, A. D. 1877.". Washington: Govt. Print. Office. Available at https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/009260947.

Vazzano, Frank P. "The Louisiana Question Resurrected: The Potter Commission and the Election of 1876." Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association 16, no. 1 (1975): 39-57. Accessed January 3, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4231436