The next public step in the 2020 presidential election will happen on January 6, 2021, when Congress meets to validate the election. If there are objections at that meeting, a formerly obscure law will be consulted to settle disputes about electors.

The 538 electors representing presidential candidates declared winners in the state contests met on Monday to cast their electoral votes as required under the Constitution’s 12th Amendment and a federal statute, 3 U.S.C. §§7-8. Former Vice President Joe Biden received 306 votes and President Donald Trump received 232 votes, with 270 votes needed to declare a winner.

The 538 electors representing presidential candidates declared winners in the state contests met on Monday to cast their electoral votes as required under the Constitution’s 12th Amendment and a federal statute, 3 U.S.C. §§7-8. Former Vice President Joe Biden received 306 votes and President Donald Trump received 232 votes, with 270 votes needed to declare a winner.

Federal law requires the states to deliver certified electoral college results to the vice president, serving as president of the Senate, and other parties by December 23. Then a joint meeting of Congress is required by the 12th Amendment to count the electoral votes and declare the winners of the presidential election. The session on January 6, 2021 starts at 1 p.m.

Objections at that meeting about electors will be settled using a process established by the Electoral Count Act of 1887. The law has its origins in the contested presidential election of 1876 between Samuel Tilden and Rutherford B. Hayes. Several states during the 1876 election sent rival electoral ballots to be considered by Congress, which lacked a procedure to decide among contested slates of electors. The short-term solution was a special 15-person commission (including five House Representatives, five Senators, and five Supreme Court justices) to decide the election, which went to Hayes. In the end, the participating Supreme Court justices cast the deciding votes, after the House and Senate members voted on party lines.

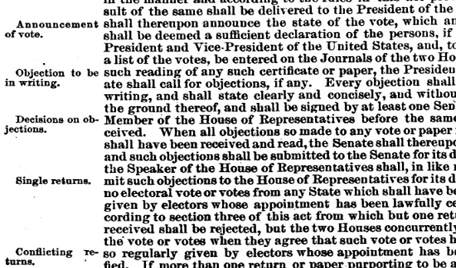

The Electoral Count Act of 1887 and several federal statutes address questions about contested electors that land in Congress. The Congressional Research Service’s current interpretation of the Electoral Count Act explains its understanding of the process when it comes to objections to electoral votes.

“Objections to individual state returns must be made in writing by at least one Member each of the Senate and House of Representatives. If an objection meets these requirements, the joint session recesses and the two houses separate and debate the question in their respective chambers for a maximum of two hours,” the CRS said. “The two houses then vote separately to accept or reject the objection. They then reassemble in joint session, and announce the results of their respective votes. An objection to a state’s electoral vote must be approved by both houses in order for any contested votes to be excluded.”

That interpretation applies to two scenarios in the 2020 election. The first is a situation where only one set of electoral votes is submitted by a state, and objections are raised on grounds that electoral votes were not “regularly given” by an elector, or that electors were not “lawfully certified” according to state laws, according the CRS.

The second scenario applies when two or more slates of electors from the same state are submitted to Congress, as was the case for the 1876 presidential election. It is unclear, said the CRS, if Congress could vote to discard a slate of electoral votes certified by a state if it followed its own election laws. “The assumption presented in the law is that only one list would be from electors who were determined to be appointed pursuant to the state election contest statute (as provided for in 3 U.S.C. §5), and that in such case, only those electors should be counted,” the CRS determined.

Regardless, as of December 15, 2020 the first scenario would seem more likely, unless a state legislature decides to send a second slate of electors to Congress and the Archivist by January 6, 2021. By December 9, 2020, all 50 states and the District of Columbia had certified their electoral votes as required by federal law.

Still, questions remain about the Electoral Count Act as a viable long-term solution to the problems it purports to resolve. Election scholar Edward Foley wrote in a Washington Post op-ed in early December about the act’s language issues. “I have spent much of my academic career trying to parse its meaning, and I still find it impenetrable or, at the very least, indeterminate,” he admitted. Various problems Foley pointed to included unclear roles of state governors and other state officials as “certifiers” and what role the vice president can play in the process.

Under the federal statute, the vice president’s role is “to preserve order” at the joint meeting. “This authority may be interpreted as encompassing the authority to decide questions of order, but the statute is not explicit on this point,” said the CRS. In past meetings, the vice president has ruled on questions about how the session should be conducted in compliance with federal statutes, which limit motions and almost all debate at the joint session. The vice president is also allowed to call for objections when electoral votes are announced and to state the results of those objections after the House and Senate meet separately to consider them.

In a 2010 law review article, Stephen A. Siegel looked at the Electoral Count Act of 1887’s history and its intent. After a lengthy analysis, Siegel found the act “a coherent enactment,” qualifying that its “coherence does not mean that it is a complete response to the problems of Congress’s electoral vote counting.” One problem, he said, was determining the majority of electoral votes needed to pick a winner if some votes were discarded by Congress from the election. Currently, 270 electoral votes are needed to win a presidential election. This presents an open issue if the 270-vote threshold should be lowered if fewer electoral votes are counted.

Others have said that the Electoral Count Act is flawed. Vesan Kasavan argued in a 2002 law review article the act was unconstitutional for several reasons, including the act’s ability to bind a future Congress to procedural rules passed in 1887.

If there is an objection to an elector or electors on January 6, 2021, there is a recent precedent. In January 2005, Representative Stephanie Tubbs Jones and Senator Barbara Boxer objected to Ohio’s electoral votes for George W. Bush, alleging “they were not in all known circumstances regularly given.” The House and Senate met separately as required and using a roll call vote the objections were widely rejected. The House denied the objection in 31-267 vote, and the Senate denied it in a 1-74 vote.

Scott Bomboy is the editor in chief of the National Constitution Center.