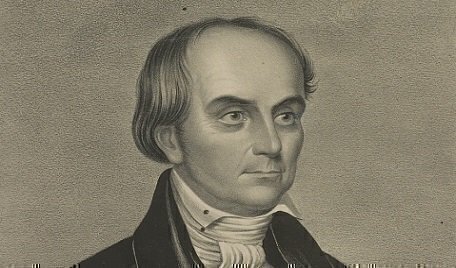

Daniel Webster was one of the seminal figures of nineteenth century America as an orator and politician. Perhaps less known is Webster’s influence on the Supreme Court, and especially the Marshall Court.

Born on January 18, 1782 in New Hampshire, Webster was an attorney before joining Congress in 1813. During his nearly 30 years in government, Webster served as Secretary of State two times, and he served in the Senate and in the House. Today, he’s best remembered as the greatest public speaker of his time, a founder of the Whig Party, and for his controversial role in the 1850 compromise that led to fugitive slave laws – and the Whig Party’s death.

But through his public career, Webster practiced the law and argued cases in front of the Supreme Court and other courts up to his death in 1852. In fact, he argued more than 200 cases in front of the Justices and was involved in several landmark cases that solidified the power of the federal government.

The late history professor Maurice G. Baxter’s book from 1966, Daniel Webster & The Supreme Court, presents a good look at Webster’s relationship with the Court. Between 1812 and 1852, a period of 40 years, “no lawyer had more effect on the United States Supreme Court, that wondrous engine of national power, than Daniel Webster,” Baxter said.

Webster’s contributions including arguing cases about interstate commerce, the rights of corporations, and the limits of common law – all matters that were unsettled during the Court’s earliest period. And while Webster gained great fame for his Supreme Court arguments, Baxter said most of his court work was outside Washington. Webster wasn’t known as a great legal scholar, but he studied scholarly works, including those from his friend, Justice Joseph Story. He was very well prepared, with detailed legal briefs that he wrote in conjunction with his associates.

It also wouldn’t be unusual for Webster to appear in Congress and argue a case at the Supreme Court on the same day, to capacity crowds wanting to hear “the Defender of the Constitution.”

Webster is most associated with three landmark Supreme Court decisions. He defended his alma mater, Dartmouth College, in the 1819 corporate-law case, Dartmouth College v. Woodward. In the newly refurbished Supreme Court chambers, Webster argued that it was unconstitutional for the state of New Hampshire to use legislation to place Dartmouth, a private college, under its control.

Webster’s four-hour oratory was so strong that after he stared at Chief Justice John Marshall at its end, most people in the courtroom were in tears, according to eyewitnesses. Marshall, in his majority opinion, agreed with Webster that the Constitution’s Contracts Clause protected private corporations like Dartmouth.

Webster also was one of the lawyers in the landmark case McCulloch v. Maryland, in 1819. The state of Maryland had placed a tax on the Second Bank of the United States branch in that state. Webster refuted Maryland’s claims that the bank was unconstitutional and that the state could tax it anyway. During opening arguments directed at Chief Justice Marshall, Webster said the federal Constitution was “the supreme law of the land,” echoing older arguments made by Alexander Hamilton. Then, Webster made his own case that the Maryland’s ability to place a levy on a federal bank would lead to unlimited state taxing power and a power to destroy federal institutions. Marshall made the same arguments in the unanimous decision that reinforced federal power under the Supremacy Clause.

In Gibbons v. Ogden (1824), Webster argued for the power of Congress to regulate commerce between the states. After the steamboat’s invention, Robert Fulton and Robert Livingston gained an exclusive right from New York State to issue permits to steamboats in Hudson Bay. The federal government granted its own permit to Thomas Gibbons to access the waterway. During his two- and a-half-hour opening argument, Webster said the federal government under the Constitution had the power to determine which powers, such as regulating commerce, were exclusive to Congress. Pointing to the debates over constitutional ratification in 1787, Webster said the Constitution “would not have been worth accepting” if the states had retained all their powers. Marshall’s decision again agreed with Webster’s arguments, expanding federal power in general and the federal government’s ability to regulate the economy.

In March 1852, Webster argued his final case, in front of a federal court in Trenton, on behalf of the Goodyear Rubber Company, while he also held the office of Secretary of State. Soon after, Webster was injured in a carriage accident and died from complications related to his injuries in October 1852.

The New York Times noted Webster’s passing and listed his legal achievements first in his obituary. “If mighty interests were at stake, or new and interesting questions involved, or if causes depended upon constitutional construction, the services were invoked of this Goliath of the North.” The Times also said that while some thought Webster was at his best in the Senate, “before the Supreme Court of the United States was the element in which he found himself most at home.”

Correction: This post originally said Webster served three times as Secretary of State.

Scott Bomboy is editor in chief of the National Constitution Center.