Historic Document

Massachusetts Circular Letter (1768)

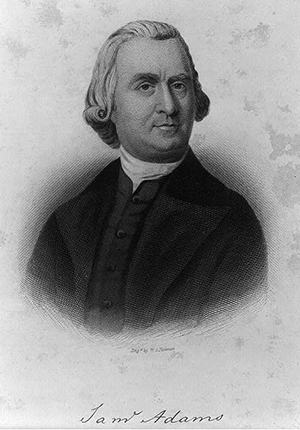

Samuel Adams and James Otis | 1768

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Summary

The Massachusetts Circular Letter was passed by the Massachusetts Assembly in protest of the Townshend Acts. It conceded that Parliament enjoyed supreme legislative power throughout the empire and pledged allegiance to the crown, but claimed that, through that allegiance, the colonists were entitled to the full protections of the British Constitution, to which both Parliament and the crown were subject. Essential to that constitution was the principle that one’s property could be taken only with one’s consent, and since Parliament did not represent the colonists, its latest taxation violated Americans’ rights. The circular was important not just for what it said, but also for the intercolonial cooperation it sought to rouse. Massachusetts sent it to the other representative bodies throughout the colonies. Concerned by the prospect of collective resistance, Lord Hillsborough, Secretary of State for the Colonies, ordered the Massachusetts assembly to rescind the circular. When they refused, Massachusetts’s royal governor, Francis Bernard, felt he had no choice but to dissolve the assembly, igniting mobbing and violence that led the British government to dispatch troops to occupy the city of Boston, further escalating the crisis.

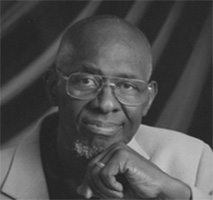

Selected by

William B. Allen

Emeritus Dean of James Madison College and Emeritus Professor of Political Science at Michigan State University

Jonathan Gienapp

Associate Professor of History at Stanford University

Document Excerpt

“The House of Representatives of this province have taken into their serious consideration the great difficulties that must accrue to themselves and their constituents by the operation of several Acts of Parliament, imposing duties and taxes on the American colonies.

As it is a subject in which every colony is deeply interested, they have no reason to doubt but your house is deeply impressed with its importance, and that such constitutional measures will be come into as are proper. It seems to be necessary that all possible care should be taken that the representatives of the several assemblies, upon so delicate a point, should harmonize with each other. The House, therefore, hope that this letter will be candidly considered in no other light than as expressing a disposition freely to communicate their mind to a sister colony, upon a common concern, in the same manner as they would be glad to receive the sentiments of your or any other house of assembly on the continent.

The House have humbly represented to the ministry their own sentiments, that his Majesty’s high court of Parliament is the supreme legislative power over the whole empire; that in all free states the constitution is fixed, and as the supreme legislative derives its power and authority from the constitution, it cannot overleap the bounds of it without destroying its own foundation; that the constitution ascertains and limits both sovereignty and allegiance, and, therefore, his Majesty’s American subjects, who acknowledge themselves bound by the ties of allegiance, have an equitable claim to the full enjoyment of the fundamental rules of the British constitution; that it is an essential, unalterable right in nature, engrafted into the British constitution, as a fundamental law, and ever held sacred and irrevocable by the subjects within the realm, that what a man has honestly acquired is absolutely his own, which he may freely give, but cannot be taken from him without his consent; that the American subjects may, therefore, exclusive of any consideration of charter rights, with a decent firmness, adapted to the character of free men and subjects, assert this natural and constitutional right.

It is, moreover, their humble opinion, which they express with the greatest deference to the wisdom of the Parliament, that the Acts made there, imposing duties on the people of this province, with the sole and express purpose of raising a revenue, are infringements of their natural and constitutional rights; because, as they are not represented in the British Parliament, his Majesty’s commons in Britain, by those Acts, grant their property without their consent.

This House further are of opinion that their constituents, considering their local circumstances, cannot, by any possibility, be represented in the Parliament; and that it will forever be impracticable, that they should be equally represented there, and consequently, not at all; being separated by an ocean of a thousand leagues. That his Majesty’s royal predecessors, for this reason, were graciously pleased to form a subordinate legislature here, that their subjects might enjoy the unalienable right of a representation; also, that considering the utter impracticability of their ever being fully and equally represented in Parliament, and the great expense that must unavoidably attend even a partial representation there, this House think that a taxation of their constituents, even without their consent, grievous as it is, would be preferable to any representation that could be admitted for them there.

…

This House cannot conclude, without expressing their firm confidence in the king, our common head and father, that the united and dutiful supplications of his distressed American subjects will meet with his royal and favourable acceptance.”