Historic Document

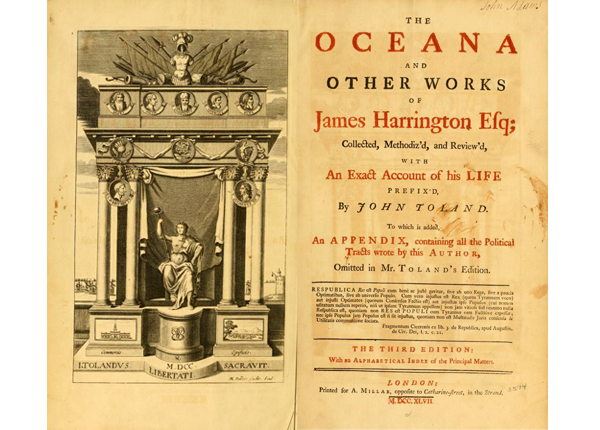

The Commonwealth of Oceana (1656)

James Harrington | 1656

John Adams Library at the Boston Public Library

Summary

James Harrington (1611-77) was the author of The Commonwealth of Oceana (1656) and other works published in its defense. Of these, only The Commonwealth of Oceana was widely read in America. A work of utopian fiction, Harrington’s Oceana described a constitutional convention – held in camera, so that the debates could be frank and that there would be no chance that the members’ deliberations would be disturbed – which produced a republican constitution for a country, called Oceana, that was clearly modeled on Great Britain. That constitution, deeply influenced by Machiavelli’s Discourses on Livy, featured a militia, an agrarian law, the secret ballot, a bicameral legislature, rotation in office, a sharp distinction between what Harrington called “the natural aristocracy” and “the natural democracy,” and an attempt to balance the two. With Machiavelli and Hobbes, Harrington believed that good government is not a product of virtue and deliberation but of process and of a channeling of interests. Although Harrington was not himself as frequently cited in the constitutional deliberations that took place in the nascent American states as were Montesquieu, Blackstone, Locke, and Hume, Harrington’s influence on the first two and the last of these thinkers and on the radical Whigs of the 1680s and after was profound; and thereby he exercised an immense influence on the revolutionary generation.

Selected by

Paul Rahe

Professor of History and Charles O. Lee and Louise K. Lee Chair in the Western Heritage at Hillsdale College

Jeffrey Rosen

President and CEO, National Constitution Center

Colleen A. Sheehan

Professor of Politics at the Arizona State University School of Civic and Economic Thought and Leadership

Document Excerpt

Oceana:

The perfection of Government lyeth upon such a libration in the frame of it, that no man or men, in or under it, can have the interest; or having the interest, can have the power to disturb it with sedition.

Give us good men and they will make us good Lawes is the Maxime of a Demagogue, and (through the alteration which is commonly perceivable in men, when they have power to work their own wills) exceedingly fallible. But give us good orders, and they will make us good men, is the Maxime of a Legislator and the most infallible in the Politickes.

There is not a more noble, or useful question in the Politicks, then that which is started by Machiavil, whether means were to be found whereby the Enmity that was between the Senate and the people of Rome, might have been removed.

A Discourse upon this Saying (1659):

The Italians are a grave and prudent nation, yet in some things no less extravagant than the wildest, particularly in their carnival or sports about Shrovetide; in these they are all mummers, not with our modesty, in the night, but for divers days together, and before the sun; during which time, one would think by the strangeness of their habit that Italy were once more overrun by Goths and Vandals, or new peopled with Turks, Moors and Indians, there being at this time such a variety of shapes and pageants. Among these, at Rome I saw one which represented a kitchen, with all the proper utensils in use and action. The cooks were all cats and kitlings, set in such frames, so try’d and so ordered, that the poor creatures could make no motion to get loose, but the same caused one to turn the spit, another to baste the meat, a third to scim the pot and a fourth to make green-sauce. If the frame of your commonwealth be no such, as causeth everyone to perform his certain function as necessarily as this did the cat to make green-sauce, it is not right.