Among the most controversial of all Supreme Court decisions happened in 1989, when a divided Court allowed flag burning as protected free speech. So how did the Court choose to make an unpopular decision about an American institution?

The battle in the courts over people burning the American flag, or doing other offensive acts to the flag, dates back to 1907. In the prior decade, states started passing laws than banned flag desecration, which not only included laws protecting the flag from physical abuse, but also from commercial abuse.

The Court said in the 1907 case of Halter v. Nebraska that two businessmen couldn’t sell beer that had flag labels on the bottles, upholding a state law.

Then a 1931 case set the first precedent for the use of a flag in an act of symbolic speech under the First Amendment, when the Court struck down a California law that banned the flying of a red flag to protest against the government.

In 1968, Congress approved the Federal Flag Desecration Law after a Vietnam War protest. The law made it illegal to "knowingly" cast "contempt" upon "any flag of the United States by publicly mutilating, defacing, defiling, burning or trampling upon it."

The Court moved toward its historic 1989 decision about flag burning in 1974, when it said in Spence v. Washington that a person couldn’t be convicted for using tape to put a peace sign on an American flag. The decision made it clear that a majority of the Court saw the act as protected expression under the First Amendment.

During the decade, states narrowed the focus on their flag desecration laws, but they still prohibited flag burning and other acts of mutilation.

The issue was then settled, at least in the Supreme Court, in the controversial Texas v. Johnson decision.

In protest of President Ronald Reagan’s administrative policies, Gregory Lee Johnson burned a flag outside the City Hall building in Dallas, Texas, in 1984. Many onlookers said the scene was deeply offensive, a sentiment that represented the popular majority’s view on the matter.

Texas arrested Johnson and convicted him of breaking a Texas state law that prohibited desecration of the flag of the United States. Johnson was sentenced to one year in prison and ordered to pay a $2,000 fine.

Johnson appealed his conviction, claiming First Amendment protection, and the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals stated that Johnson’s speech was symbolic and ruled in his favor.

The Supreme Court took the case, and in a very unusual majority, the Court voted 5-4 in favor of Johnson. Johnson’s actions, the majority argued, were symbolic speech political in nature and could be expressed even at the affront of those who disagreed with him.

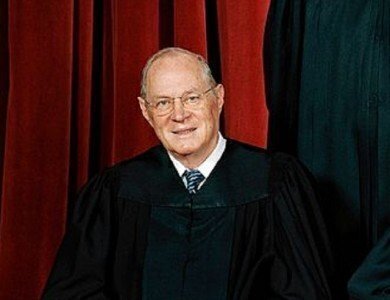

Justice Anthony Kennedy, writing a regular concurrence, spelled out his reasoning succinctly.

“The hard fact is that sometimes we must make decisions we do not like. We make them because they are right, right in the sense that the law and the Constitution, as we see them, compel the result,” Kennedy said. “And so great is our commitment to the process that, except in the rare case, we do not pause to express distaste for the result, perhaps for fear of undermining a valued principle that dictates the decision. This is one of those rare cases.

“Though symbols often are what we ourselves make of them, the flag is constant in expressing beliefs Americans share, beliefs in law and peace and that freedom which sustains the human spirit. The case here today forces recognition of the costs to which those beliefs commit us. It is poignant but fundamental that the flag protects those who hold it in contempt,” he said.

Chief Justice William Rehnquist, in his dissent said that, “the flag is not simply another ‘idea’ or ‘point of view’ competing for recognition in the marketplace of ideas.”

“I cannot agree that the First Amendment invalidates the Act of Congress, and the laws of 48 of the 50 States, which make criminal the public burning of the flag,” he said.

In reaction to the Johnson decision, which only applied to the state of Texas, Congress passed an anti-flag burning law called the Flag Protection Act of 1989.

But in 1990, the Court struck down that law as unconstitutional.

“If there is a bedrock principle underlying the First Amendment, it is that the Government may not prohibit the expression of an idea simply because society finds the idea itself offensive or disagreeable,” said Justice William Brennan.

The case remains controversial to the present day, and Congress has, as recently as 2006, attempted to amend the Constitution to prohibit flag desecration, with the effort failing by one vote in the Senate.