The current controversy over the Speaker of the House of Representatives has highlighted that position’s role as one of the most important elected officials in Washington. But little was spelled out in the Constitution about the position and how the House selected the Speaker.

The Speaker is usually selected during party meetings before a new Congress meets, and the House confirms the selection by individual voice votes. The clerk of the House presides over the voting process. Before 1839, secret ballots were used in voting. Until this year, there hasn’t been a Speaker election contested on the House floor since 1923.

The Speaker is usually selected during party meetings before a new Congress meets, and the House confirms the selection by individual voice votes. The clerk of the House presides over the voting process. Before 1839, secret ballots were used in voting. Until this year, there hasn’t been a Speaker election contested on the House floor since 1923.

The Constitution’s Article 1, Section 2, spells out a very broad role for the Speaker: “The House of Representatives shall chuse their Speaker and other Officers; and shall have the sole Power of Impeachment.” The Founders’ vision appeared to be for the Speaker to serve as a parliamentarian and peace maker, more along the lines of the Speaker in the British House of Commons. There wasn’t a detailed description of the Speaker’s role in The Federalist, the collection of essays written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay. But the role changed as the political scope of the national government grew as the Founding era ended.

In 1811, Henry Clay became the first dynamic national political figure to assume the role of Speaker of the House. Since Clay’s three terms in the House, various Speakers have used different leadership styles in their critical jobs as national party spokesperson and House institutional leader. Since Clay’s time, the role of Speaker of the House has become more complex as the size of government has grown.

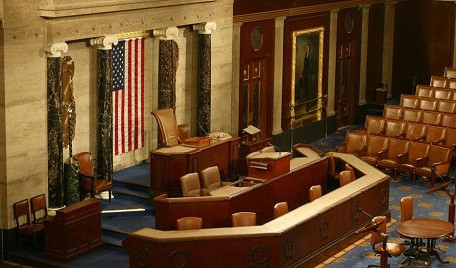

Today, the Speaker of the House serves in several major constitutional roles. The Speaker is the majority political party leader in the House, which on its own is one of the most powerful jobs in Washington. In addition, the Speaker controls the order of all institutional business on the House floor. The Speaker also votes on business as needed as a representative from a district.

In these positions, the Speaker plays a key role as negotiator between the House and president and with the Senate, and as the point person for the House’s fundamental role in originating and passing legislation and controlling “the power of the purse” to tax and spend taxpayer money.

The Speaker also is second-in-line (after the vice president) to the presidency under the Presidential Succession Act of 1947, and the Speaker plays a role in the 25th Amendment’s process of dealing with the event of a presidential disability.

A list of the most prominent House Speakers since Clay includes Schuyler Colfax, James G. Blaine, Thomas Reed, Joseph Cannon, Champ Clark, Sam Rayburn, Joseph Martin, John McCormack, Tip O’Neill, and Newt Gingrich. And only one former House Speaker has been elected president: James Knox Polk.

The Speaker’s role within the House has also seen some important changes since 1789. Under the guidelines of Jefferson’s Manual, which serves as a foundation for the House’s rules, the Speaker originally didn’t talk on the House floor during debates and only spoke when conducting parliamentary manners. According to the Congressional Research Service, Clay was first Speaker to occasionally “speak” on the House floor during debates in the Committee of the Whole, but usually the Speaker only takes part in floor debates when there is a need to “to highlight or rally support for the majority party’s agenda,” says the CRS. Also, the Speaker didn’t get a clear right to vote on all House matters until 1850.

And there is one interesting, unique footnote about the Speaker of the House position: The job candidate doesn’t have to be a member of the House of Representatives. But as of 2023, no person has been chosen as Speaker who was not a member of the House.

Editor’s Note: Sections of this story first appeared in a 2018 post on Constitution Daily about the process to choose a successor to Paul Ryan.

Scott Bomboy is the editor in chief of the National Constitution Center.