As the Trump administration gets ready to take over the executive branch next month, there is a still an on-going debate about Jared Kushner’s role in Washington. But in the history of presidential in-laws, Kushner’s influence may pale in comparison to a long-forgotten Treasury Secretary.

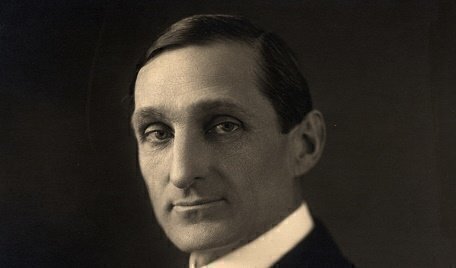

The name of William Gibbs McAdoo is well-known among financial historians. McAdoo helped expand the United States as a global financial power during World War I, when he ran three key government financial agencies. He was also President Woodrow Wilson's son-in-law.

The speculation is that President-elect Trump wants Kushner in an advisory position in his new administration. Critics point to a 1967 law, the Federal Anti-Nepotism Statute, as preventing this. The statute, known as Section 3110, was passed as part of a Postal Service reform law, and it states that an executive agency official can’t appoint relatives, including sons, daughters and sons-in law, to “a civilian position in the agency in which he is serving or over which he exercises jurisdiction or control.”

However, others have said that if Kushner, or another Trump family member, is in an unofficial role and doesn’t receive compensation, there isn’t a conflict with the statute.

The 1967 law came about after President John F. Kennedy’s nomination of his brother, Robert, to become Attorney General. Before then, there was a long history of presidential relatives performing official (and sometimes, unofficial) jobs in administrations. In 1797, incoming President John Adams retained his son, John Quincy Adams, as a diplomat and appointed him as the United States minister to Prussia, over public criticism. Adams also nominated his son-in-law, William Stephens Smith, for several government positions.

Other Presidents retained relatives at the White House in secretarial roles, including James Madison, James Monroe, Andrew Jackson, John Tyler and James Buchanan. Zachary Taylor kept his brother and son-in-law on the government payroll. Franklin Roosevelt and Dwight Eisenhower had family members as secretaries or aides. In the 1990s President Bill Clinton asked Hillary Clinton to lead a health-care task force.

But in terms of pure power and influence, few presidential relatives had the direct responsibilities of McAdoo, who ran much of the American financial system during the World War I era.

McAdoo became Wilson’s son-in-law in 1914 when he was already a member of Wilson’s cabinet as his Treasury Secretary. McAdoo married Wilson’s daughter, Nellie, at the White House. A fellow southerner who moved north, McAdoo managed Wilson’s successful presidential campaign in 1912, despite dealing with his first wife’s death in early 1912.

Wilson knew McAdoo from McAdoo’s work as president of Hudson and Manhattan Railroad Company, which built the first successful under-river subway tunnels in New York City. As Treasury Secretary, McAdoo soon inherited some severe economic problems that called for bold solutions.

In July 1914, war was on the horizon in Europe and in order to stop a run on the New York Stock Exchange, McAdoo ordered the stock exchange closed for a four-month period. The radical move forced more gold into the American economy and started the process of the United States becoming a creditor, and not a debtor, nation. At that point, McAdoo had also become the first chairman of the Federal Reserve Board. He ensured that emergency currency was placed in use to stabilize the American economy and that ships exporting American goods to Europe were insured by the federal government against loss.

When the United States went to war in 1917, McAdoo led efforts to raise money to fund the Allied fight against the Axis powers. And in late 1917, President Wilson nationalized the nation’s railroad systems to aid the war effort, placing McAdoo in charge of all railways as director general of the U.S. Railroad Administration.

McAdoo resigned his three positions in late 1918 after the war ended in Europe for several reasons.

“For almost six years I have worked almost incessantly under the pressure of great responsibilities. The exactions have drawn heavily on my strength,” McAdoo wrote at the time. He also pointed out that he had personal financial problems because of the poor compensation for cabinet members in Washington, and he wanted to “get back to private life, to retrieve my fortune.”

The second chapter in McAdoo’s public life was more dramatic, but not as successful. McAdoo was seen as the favorite for the 1920 Democratic Party presidential nomination, but his father-in-law, Wilson, harbored hopes that a deadlocked convention would turn to him for a third term. That prevented McAdoo from publicly campaigning for the nomination.

McAdoo’s name was placed in nomination at the convention in San Francisco and he led on the early ballots, but the deadlocked convention went to Ohio Governor James Cox, who lost to Warren Harding in the general election

In 1924, McAdoo was again the favorite for the Democratic nomination and he led the majority of the 103 ballots taken at Madison Square Garden in New York, in a convention noted today for the influence of the Ku Klux Klan (which supported McAdoo). In the end, John W. Davis was the compromise candidate, ending McAdoo’s presidential aspirations.

After returning to private life, McAdoo resurfaced a United States senator from California in the 1930s. He died in 1941 in Washington, D.C. after attending President Franklin Roosevelt’s inauguration.

Scott Bomboy is the editor in chief of the National Constitution Center in Philadelphia.