In part two of a special three-part series, Constitution Daily looks at the filibuster’s emergence in the Senate era of “unlimited speech” from 1806 to 1917, and why the House of Representatives killed its filibuster. In case you missed it, part one discussed the disucssed the filibuster's origins in the early sessions of the Senate.

The Senate’s decision in 1806 to eliminate its previous question motion didn’t immediately create the filibuster. That motion, in theory, would limit the time for floor speeches and prevent a small number of Senators from blocking legislation or appointments.

The Senate’s decision in 1806 to eliminate its previous question motion didn’t immediately create the filibuster. That motion, in theory, would limit the time for floor speeches and prevent a small number of Senators from blocking legislation or appointments.

Over time, the Senate’s members honed delaying moves into a system that became known as the filibuster. The combination of prolonged floor speeches and attendance votes became more effective and prevalent after the 1870s.

The House of Representatives took a different approach to “unlimited speech” on its floor and soon tired of filibustering efforts. The House kept the previous question motion after 1806 and it still allowed speeches intending to block votes until the early 1840s. By then, the classic age of the filibuster was just beginning in the Senate, but it was mostly ending in the House.

The House saw the first test of its previous question motion in 1810, when the Rep. Barent Gardenier, a Federalist, opposed a motion supporting President James Madison in the escalating conflict with Great Britain. Gardenier had a well-earned reputation as a long speaker, and he spoke for six hours in a failed attempt to block that motion. He tried a similar tactic a year later, when he started a speech at 2:30 a.m. to delay a trade embargo against the British.

Rep. Thomas Gholson had enough of Gardenier and called for the previous question to end Gardenier’s speech. House Speaker Joseph Varnum let Gardenier continue, but Gholson repeated the same motion. Speaker Varnum allowed the entire House to vote on the matter. In a 66-13 vote, the members set the precedent that the previous question motion could end floor debate in the House.

In 1841, the House further limited debate by establishing a rule that limited speakers to 60 minutes on the floor. To be sure, the rule changes were significant, but they didn’t fully stop House members from using other “dilatory” tactics to delay a vote. Most notorious of these was the disappearing quorum, when members would refuse to vote or leave the House floor when a representative asked the Speaker to confirm if enough members were participating to the House to hold a vote or take action.

The Constitution’s Article 1, Section 5, gave the House the authority to determine the appropriate quorum to conduct business. In 1890, House Speaker Thomas Reed, a Republican, abruptly killed the disappearing quorum precedent when he told the House clerk that all members present in the room counted toward the quorum, including those who refused to vote or speak. In 1892, the Supreme Court upheld Reed’s ruling in United States v. Ballin. “All that the Constitution requires is the presence of a majority, and when that majority are present the power of the House arises,” wrote Justice David Brewer.

The Senate Keeps the Filibuster

By 1892, the Senate had taken a much different approach to delaying tactics in its chambers. The filibuster was fully entrenched in the Senate’s proceedings and many members considered “unlimited speech” a big part of the Senate’s legacy, especially those minority party members who skillfully used the dilatory tactics discarded by the House of Representatives to block a Senate majority.

In 1841, as the House moved to cut off unlimited debate, the Senate had its first prominent early filibusters over patronage in its printing office and then a long-contested national banking bill dating back to the Andrew Jackson administration. The first filibuster ended in defeat for the minority-party Democrats; the second concluded with a compromise that the Senate approved and sent to President John Tyler, who promptly vetoed the bill.

By 1863, the word “filibuster” came into use in the Senate to describe the process of blocking votes or the passage of a bill. The term’s association with pirating and buccaneering was seen in offensive terms, said scholars Catherine Fisk and Erwin Chemerinsky. They noted in a 1997 study that only six recognized filibusters appeared in the Senate’s records before 1863.

A generation later, the filibuster assumed a bigger role in the Senate’s proceedings. Starting in the 1880s, filibusters became more commonplace and successful for the filibustering parties. In 1890, a successful filibuster blocked an “election bill” or “force bill” to place federal troops at polling places to block intimidation against Black voters. From December 2, 1890 to January 22, 1891, the minority Democratic caucus used publicity tactics to make the filibuster a public fight, and then it found support from a small number of Republicans who needed support of their own in the Free Silver debate.

Three years later, the tables turned when a coalition of pro-silver Republicans and “Farmer Democrats” in the Senate failed to block the Cleveland administration’s repeal of mandatory government silver purchases. The filibuster consumed 46 days on the Senate calendar and ended with the Farmer Democrats dropping their alliance with the Republicans. During the debates, Republicans pushed for the Senate to consider cloture, or a motion to place a time limit on the filibuster.

A Little Group of Willful Men

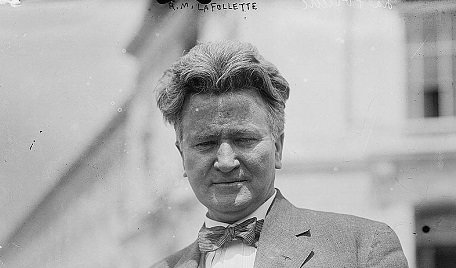

A brief filibuster in 1908 started an effort to restrain filibuster tactics. The issue in this case was a currency bill backed by the conservatives in the Republican administration to allow bonds to prop up the securities market. Senator Nelson W. Aldrich led the majority efforts, opposed by another Republican, Robert La Follette of Wisconsin. “Fighting Bob” LaFollette was a leading national Progressive figure and a speaker of legendary stature. He also strongly opposed party bosses such as Aldrich.

Before La Follette spoke, the Senate Vice President, Charles W. Fairbanks ruled that Senators who remained silent during a vote were now counted in the quorum. Then, LaFollette took the Senate floor at 12 p.m. on May 29, 1908, and he spoke for the next 18 hours against the currency bill, aided by roll call votes to determine a quorum. However, when Aldrich objected to a quorum request from La Follette, Vice President Fairbanks let the full Senate rule on Aldrich’s objection. By a 35-8 vote, the Senate limited La Follette to just two quorum calls before he had to surrender the floor. The Senate, in less than two days, had partially reigned in the unlimited speech filibuster.

In 1915, another contentious filibuster over a bill to buy merchant ships ended after 33 days, with a coalition of Republicans and conservative Democrats blocking the legislation. But part of those debates included a Democratic demand for cloture rules to place a time limit on the filibuster. And on March 2, 1917, global events finally forced cloture on the Senate. As the United States prepared to enter World War I, a group of 11 Senators successfully filibustered against a bill allowing President Woodrow Wilson to arm United States merchant ships.

Wilson publicly condemned the group. “The Senate of the United States is the only legislative body in the world which cannot act when its majority is ready for action. A little group of willful men, representing no opinion but their own, have rendered the great Government of the United States helpless and contemptible,” Wilson told the press.

On March 5, 1917, the Senate met in special session and three days later the new cloture rule passed by a vote of 76 to 3 with little debate. Senator La Follette was one of the three “no” votes. The rule, now known as Rule XXII, was a compromise between those who wanted a simple majority to end debate, like the House’s previous question motion, and those who wanted a higher threshold. It would take 16 Senators to request a cloture vote and two-thirds of those voting in the Senate to invoke cloture. Once invoked, a Senator could speak for no more than one hour and amendments could only be made by unanimous consent of the Senate.

It had been 111 years since the Senate had a rule to limit debate, but the filibuster was hardly finished. Fisk and Chemerinsky remarked that “for nearly fifty years after its adoption, Rule XXII served a purpose more symbolic than real.” Cloture was only sought 16 times in the Senate between 1917 and 1964, but those battles played an important part in the debate over civil rights and in the formation of the current filibuster system in the 1970s.

Scott Bomboy is the editor in chief of the National Constitution Center.