In this three-part series, Constitution Daily looks back at the filibuster’s early history, examines its traditional use in the Senate, and reviews the current state of the filibuster. In part one, the Constitution’s drafters and their immediate successors face the problem of limiting debate on the legislative floor.

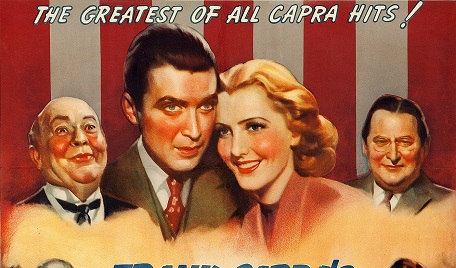

One of the classic images in modern film is from Frank Capra’s Mr. Smith Goes to Washington from 1939, when Jimmy Stewart’s character collapses after undertaking a 25-hour-long filibuster on the Senate floor.

One of the classic images in modern film is from Frank Capra’s Mr. Smith Goes to Washington from 1939, when Jimmy Stewart’s character collapses after undertaking a 25-hour-long filibuster on the Senate floor.

The filibuster remains fresh in the news today as some Senators want a rules change to allow a simple majority vote to bring the Senate’s new voting rights legislation to the floor for consideration. For now, at least 60 Senate members must vote for cloture, or to end a debate if a member threatens a filibuster, to get a floor vote. It is not the old-fashioned “Jimmy Stewart filibuster,” also known in modern times as the “speaking” or “talking” filibuster. Without 60 votes, many proposed laws remain in limbo under the terms of the “silent filibuster,” where just the threat of a filibuster can stop a law in its tracks.

When was the filibuster created? How has the filibuster changed over time? And why does it remain in place today in the Senate when the House of Representatives ditched its filibuster rules in 1842? Part of the answer to those two questions dates back to the Founders’ time and the mystery of the filibuster’s creation.

To Vote or Not To Vote

Concerns over delaying tactics in the Senate are not new. A congressional rulebook written in 1801 by Thomas Jefferson expanded on the use of the “previous question” (or PQ) motion, which forced a decision on a Senate vote, with the support of a simple majority. But in 1806, the Senate eliminated its PQ motion as part of a rules consolidation suggested by Aaron Burr, and within a generation, prolonged debates were used more often to delay or kill legislation in the Senate without a way to stop them. By the 1850s, the tactic had acquired a nickname, the “filibuster,” a word then associated with illegal pirating expeditions.

Eventually, the Senate brought back a modern version of its PQ motion in 1917. Since then, the Senate’s cloture rule has allowed lawmakers to end a filibuster using a supermajority of votes to limit time for a debate. But cloture also established a much higher bar that the old-fashioned PQ motion, making it easier for someone or some group to block legislation.

The debate about the PQ motion was hardly a new one to Thomas Jefferson. In Legislative Procedure: Parliamentary Practices and the Course of Business in the Framing of Statutes from 1922, Robert Luce wrote that the tradition of obstructing legislative voting went back to the Roman empire, when lawmakers sought to delay votes. According to Luce, Julius Caesar and Cato the Younger took part in efforts to obstruct votes in the Roman Senate. In one instance, Caesar had Cato removed from the Forum when Cato undertook a filibuster over an agrarian reform measure. Cato then returned to the Senate and kept making the same arguments. “It all might have happened much the same yesterday in some American legislature,” Luce remarked.

Rules against obstruction had their origins in the English Parliament in 1604 when the House of Commons allowed its speaker to contain “superfluous motions” or “tedious speech” on the floor. Luce noted the Pennsylvania Assembly in 1703 added rules to its proceedings to “put the matter in debate to the vote.” A version of the PQ motion was used in the Second Continental Congress and in colonial assemblies. An early filibuster in the House of Representatives occurred in June 1790 when the House and Senate disagreed over locating Congress in Philadelphia, and Elbridge Gerry took part in delaying tactics in the House during a rainstorm.

Jefferson’s manual from 1801 was brief on the issue of obstructing debate: “No one is to speak impertinently or beside the question, superfluously or tediously.” In 1968, scholar Richard R. Beeman noted in Political Science Quarterly an important distinction in how the First Congress, which had many Founders among its members, viewed the PQ motion. The motion was included in the Senate’s rules in 1789 and was intended to postpone discussion on a matter of debate, and not allow it to move forward to a vote, Beeman concluded. But on four occasions before 1806, the Senate also allowed the PQ motion to bring a matter to a vote, with limited effectiveness, Beeman said.

The Senate Deletes The PQ Motion

In 1805, the PQ motion’s time in the Senate ended when Aaron Burr, the outgoing vice president, recommended the chamber get rid of it. In his memoirs, John Quincy Adams noted Burr’s statement to the Senate was for the chamber to abolish the motion because “its purposes were much better answered by the question of indefinite postponement," which put off a vote and ended a debate. The motion left the Senate rule book in 1806.

Burr’s role in the filibuster’s history and the PQ motion’s importance remain an unsettled issues among modern scholars. In 1997, Catherine Fisk and Erwin Chemerinsky wrote an extensive analysis of the filibuster for the Stanford Law Review. “The historical record resists simple characterization. It is unclear whether the previous question, in the form then practiced, served as a device to bring a measure to a vote, or whether it served to defer discussion of sensitive or embarrassing questions. The one issue on which both sides agree, however, is that the previous question motion was seldom used before the Senate abolished it in the 1806.”

In 2010, Sarah Binder from the Brookings Institution brought more attention to Burr’s role in the filibuster’s history, when her Senate testimony included a reference to Burr. “When we dig into history of Congress, it seems the filibuster was created by mistake. The House and Senate rule books in 1789 were nearly identical. Both rule books included what is known as the previous question motion. The House kept their motion. Today it empowers a majority to cut off debate. The Senate no longer has that rule,” Binder told the Senate. “They seemed to get rid of the rule by mistake because Aaron Burr told them to.”

Other scholars have viewed Burr and the PQ motion as of limited importance. Gregory Koger from the University of Miami believes that the previous question role in 1805 isn’t fully understood today. “In early usage, this motion did not end debate; it offered listeners an opportunity to decide whether debate should go on, so if a majority supported a PQ motion, debate continued,” Koger wrote in April 2021. Koger placed much more of the blame on legislative majorities than Aaron Burr for the filibuster’s persistence today.

To be sure, at a time when the Constitution was barely 20 years old, there was not a lot written on the record in 1806 about what later would be called the filibuster. Also, there was no mention of voting obstruction in the Constitution, which granted authority to Congress to make almost all of its own rules.

In 1940, historian Franklin L. Burdette pointed out a problem for future filibuster scholars: “For many of the proceedings of the early Senate, and in the case of the early House, historians are dependent upon contemporary commentaries and upon private records left by the members. Debates in Congress were often scantily reported, and in the Senate they were secret till 1794.”

Whether the PQ motion’s presence in the Senate rules after 1806 could have prevented the next century of filibustering remains a matter of conjecture. Back in 1968, Beeman recounted the impact that Jefferson’s 1801 call for civility had on Congress until the Civil War: “Jefferson’s dictum was to meet many challenges; in almost every instance it failed to withstand the test.”

Next In Series: The Classic Age of the Filibuster

Scott Bomboy is the editor in chief of the National Constitution Center.