On March 20, 1854, disgruntled voters met in Wisconsin to start a new political party to contest the Democrats and a third long-forgotten party, the Whigs. But the Republican Party’s birth is somewhat hazy in its early days.

For a brief time in the decade before the Civil War, the Democratic Party of Andrew Jackson and his descendants enjoyed a period of one-party rule.

The Democrats had battled the Whigs for power since 1836 and lost the presidency in 1848 to Zachary Taylor. But the Whig Party dramatically collapsed in the few short years after Taylor died in office in 1850.

By 1854, the battle between pro-slavery and anti-slavery forces ended the Whig party as a force in American politics. The Kansas-Nebraska Act was passed, allowing new territories and states to decide on their own if they would allow slavery. The act was a fatal blow to unity within the Whig Party.

There are at least three dates recognized for the birth of the Republican Party in 1854. The first is February 24, 1854, when a small group met in Ripon, Wisconsin, to discuss its opposition to the Kansas-Nebraska Act. The group called themselves Republicans in a reference to Thomas Jefferson’s Republican faction in the American republic’s early days.

The second meeting was larger, on March 20, 1854, in Ripon, to formally recognize and popularize the movement in Wisconsin. A third meeting in Jackson, Michigan, on June 6, 1854, was attended by about 10,000 people.

Horace Greeley, the newspaper publisher, had officially christened the group as Republicans in an editorial.

"We should not care much whether those thus united [against slavery] were designated 'Whig,' 'Free Democrat' or something else; though we think some simple name like 'Republican' would more fitly designate those who had united to restore the Union to its true mission of champion and promulgator of Liberty rather than propagandist of slavery,” he wrote.

The Republicans made quick inroads with their anti-slavery platform in the 1854 elections as a regional party, with its candidate becoming Michigan’s governor.

But the Republicans had rivals in other northern states popularly called the Know Nothings (or the Native American or American party). That rival party was loosely organized and campaigned on an anti-immigrant platform; it faded away after 1856, also divided over slavery.

The Whig party also had a minimal presence in 1856. Former president and former Whig Millard Fillmore ran for president with the Know Nothing Party. But he finished third, and Democratic candidate James Buchanan became president.

In two short years, the Republicans had become a force in the North, and their 1856 candidate, John Fremont, won 114 electoral votes and finished second to Buchanan, despite the lack of any Republican presence in the South.

The Democrats’ popular vote total fell from 50 percent in 1852 to 45 percent in 1856.

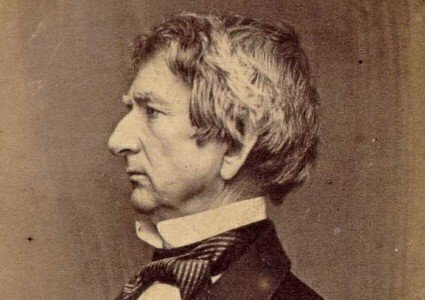

Among the early leaders of the national Republican Party was William Seward, a former Whig and staunch enemy of slavery. Another former Whig, Abraham Lincoln, sought the party’s vice presidential nomination in 1856, but came in second at the party’s first convention in Philadelphia.

By 1858, Lincoln became a national figure after a series of debates with the architect of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, Senator Stephen Douglas. Lincoln lost the Senate race in Illinois to Douglas, but the debates made slavery and the Dred Scott decision a cause in the North.

In 1860, Lincoln gained an upset nomination over Seward at the Republican Convention and was able to win the presidency over a divided Democratic Party.

Lincoln’s win capped a startling six-year rise for the Republicans from obscurity to controlling the White House. And with the exception of a pair of terms served by a Democrat, Grover Cleveland, the Republicans controlled the White House from 1860 until 1912.