On October 24, 1861, a group of delegates in 39 Virginia counties decided to start the process of forming their own state during the Civil War, beginning a constitutional debate that continues to this day.

The federal government later recognized West Virginia as a state on June 20, 1863, while at the same time Virginia, one of the original signers to the Constitution, remained in rebellion. But soon after the Civil War concluded, questions started popping up about West Virginia’s unusual path to statehood. A 6-3 Supreme Court decision in 1870 seemingly recognized the legitimacy of West Virginia, but it didn’t directly rule on whether the creation of the state was constitutional.

The counties of northwestern Virginia had disputes with eastern Virginia that well-preceded the Civil War about voter representation and property. Those problems came to a head in April 1861 when Virginia’s governor and legislature approved of the state’s secession from the federal government. A subsequent referendum approved the withdrawal from the Union on regional voting lines.

Union troops then occupied the northwest part of Virginia, and local delegates who had voted against Virginia’s secession approved a move to reorganize the official government of Virginia in the western part of the state. It was known as the Restored or Reorganized Government of Virginia and it sent representatives to Congress, and it eventually relocated to Alexandria, Virginia during the war.

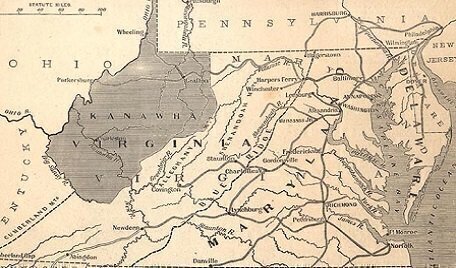

At the same time, a movement started to create a new state, initially called Kanawha and then West Virginia, at a second regional convention in Wheeling. Under the terms of the Constitution’s Admissions Clause, the delegates appealed to the Restored Government to start the statehood process.

Article IV, Section 3, states that “New States may be admitted by the Congress into this Union; but no new State shall be formed or erected within the Jurisdiction of any other State; nor any State be formed by the Junction of two or more States, or Parts of States, without the Consent of the Legislatures of the States concerned as well as of the Congress.”

The referendum on October 24, 1861 approved the pursuit of statehood for West Virginia with the backing of the Restored state government. During the next year, West Virginia seemed headed for statehood even though the issue of slavery within the new state was unsettled. Congress approved the West Virginia statehood resolution and sent it to the White House for the President’s signature

In December 1862, President Abraham Lincoln asked his cabinet members about their opinions on the resolution’s constitutionality, and they appeared to be evenly split. Lincoln signed the bill in late December but he included some caveats in an opinion statement.

Lincoln argued that the absence of potential voters from eastern Virginia didn’t matter. “It is not the qualified voters, but the qualified voters, who choose to vote, that constitute the political power of the state,” he claimed. But Lincoln also voiced reservations. “The division of a State is dreaded as a precedent. But a measure made expedient by a war, is no precedent for times of peace. It is said that the admission of West-Virginia, is secession, and tolerated only because it is our secession. Well, if we call it by that name, there is still difference enough between secession against the constitution, and secession in favor of the constitution,” Lincoln concluded.

Thaddeus Stevens voted for admitting West Virginia, but he clearly thought it was justified as a war-time act. “I will not stultify myself by supposing that we have any warrant in the Constitution for this proceeding,” Stevens reportedly said.

The question indirectly came before the Supreme Court in 1870 in a case called Virginia v. West Virginia about the inclusion of two Virginia counties within West Virginia. In the majority opinion, Justice Samuel Miller recounted the entire history of West Virginia’s admission to the Union.

“Accordingly on the 31st of December, 1862, Congress acted on these matters, and reciting the proceedings of the Convention of West Virginia, and that both that convention and the legislature of the State of Virginia had requested that the new State should be admitted into the Union, it passed an act for the admission of said State, with certain provisions not material to our purpose,” Miller said, not contesting the Restored Government as the official state of Virginia during the war. (In another Supreme Court decision in 1911, Virginia acknowledged the existence of West Virginia as a state.)

In modern times, one academic debate is about the punctuation of the Admissions Clause, and if the strict meaning of the second semi-colon in Article IV, Section 3, bars the creation of any state from the existing territory of a current state.

In 2003, scholars Vasan Kesavan and Michael Stokes Paulsen called the constitutionality of West Virginia “amazingly complicated.” But they concluded that based on debates at the Philadelphia Convention in 1787, the Founders probably intended for the Constitution to allow new states to be formed from existing states, with the proper consent of all parties involved.

Scott Bomboy is the editor in chief of the National Constitution Center.