On December 6, 1865, the 13th Amendment was ratified after the state of Georgia approved the amendment as it was proposed to the states by Congress. That act officially ended the practice of slavery in the United States.

The brief, 47-word amendment abolished an institution that had its roots in the British Colonial era and dominated much of the political, social and economic life in the United States for more than two centuries.

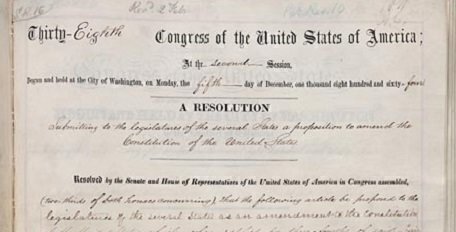

The amendment reads as follows:

Section 1. Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

Section 2. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

The amendment was a top priority for the late President, Abraham Lincoln. In January 1863 Lincoln had issued the final version of the Emancipation Proclamation, which declared “all persons held as slaves within any State, or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.” With the rebellion ending, it became imperative to get the 13th Amendment ratified to outlaw slavery within the United States.

It was approved in the Senate on April 8, 1864, and by the House on January 31, 1865. On February 1, 1865, Lincoln approved the Joint Resolution of Congress submitting the proposed amendment to the states, a little more than two months before his death at the hands of an assassin who supported slavery.

Still, 27 of the 36 states had to ratify the amendment for it to become part of the Constitution, and some of those states had been in rebellion during the Civil War. Lincoln and the Radical Republicans struggled to get the House to pass the amendment, but they finally succeeded in securing a 119–56 vote.

It came down to a group of four Southern, former Confederate states, to ensure the 13th Amendment’s passage. Two Union states, Delaware and New Jersey, had already rejected the 13th Amendment, as had two Southern states, Kentucky and Mississippi. Three Western states, Iowa, California and Oregon, as well as Florida and Texas, had yet to vote on it.

However, South Carolina (November 13, 1865), Alabama (December 2, 1865), North Carolina (December 4, 1865) and finally Georgia (December 6, 1865) agreed to ratify the amendment. Secretary of State William Seward officially certified the amendment on December 18, 1865.

Subsequently, the nine states that rejected or didn’t act on the 13th Amendment approved it, but it took Mississippi until 1995 to do so.

The public reaction, as seen in contemporary newspapers, was strong. “We are certain, then, that slavery in the land is dead in the law and letter beyond hope of resurrection, and that it has been burled by the official sextons of twenty-seven States,” said the New York Tribune.

“A strange, grateful, and animated emotion beats in our veins at the thought of the United States Government declaring with its official lips that American slavery is no more forever,” said the New York Independent.

“Freedom is national, for slavery is dead. No more to be revived, no more to breed dissensions, no more to incite war, no more to clutch at the heart of the people, and steal the life blood of the fairest and noblest of the land,” said the Springfield (Mass.) Union.

But others saw another effect of the 13th Amendment’s ratification: signaling to the country that the former Confederate states would rejoin the United States as equal political participants.

The New York Times said the ratification and certification of the 13th Amendment “is the first official recognition by the government of the constitutional equality of the late insurrectionary states with the other states.”

“We may rightfully claim . . . that our state is fully entitled to be placed in that position in the Union where she will stand as the political equal of any other state under the Federal constitution,” said Alabama Governor Robert Patton in his inaugural address.

Patton lost two sons fighting for the Confederate side in the war. “How far governmental action may be able to promote the common interest of the two races in their suddenly changed conditions is a great problem that time alone can solve,” he said.

Within two years, Patton would be replaced in all but name by a military commander during Reconstruction, and it would take several years for the former Confederate states to be officially readmitted to the Union. Ratification of the 14th Amendment was a requirement for those states to gain representation again in Congress.