On September 6, 1901, the popular President William McKinley was shot at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, while his Vice President, Theodore Roosevelt, was in Vermont at a speaking engagement. Over the next eight days, McKinley’s health condition varied until he died on September 14.

McKinley had led America out of a recession, won a war and re-election, and he was about six months into his second term as President. The Exposition had been postponed during the Spanish-American War, and McKinley wanted to be at an event that showcased the United States’ role as a regional power.

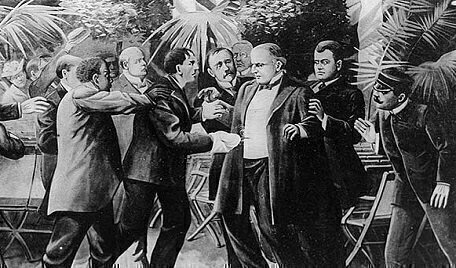

While in Buffalo, he went against the advice of his staff by agreeing to extend a long round of public handshaking with an appearance at the exhibition’s Temple of Music. Toward the end of his scheduled appearance, Leon Czolgosz, a self-avowed anarchist, shook McKinley’s left hand while shooting twice at the President.

After about eight days, President McKinley died early on September 14 from an infection caused by a gunshot wound to the abdomen, which may have been worsened by a medical team that didn’t use modern sanitary precautions during surgery. And for 13 hours, as Roosevelt made his way back to Buffalo using a horse-drawn wagon and then train travel, the office of President technically remained vacant.

Until the ratification of the 25th Amendment in 1967, presidential succession due to death or disability was handled under a precedent set by Vice President John Tyler in 1841. After President William Henry Harrison’s death, Tyler declared himself as the office holder of President on April 6, 1841, two days after Harrison’s death, by taking a new presidential oath.

In the ensuing years, three other Vice Presidents became President under similar circumstances. Millard Fillmore and Andrew Johnson were near their fallen Presidents in Washington at the time of their deaths, while Chester Alan Arthur was in New York City awaiting word about President James Garfield’s condition when Garfield died.

At the time of McKinley’s shooting, Roosevelt had been at Lake Champlain, speaking at a fish and game event. It was there that the Vice President was told of the shooting on September 6. He left by rowboat, yacht, and train to get to Buffalo, where he stayed with an old friend, Ansley Wilcox.

Roosevelt, believing reports that McKinley would recover, left Wilcox’s Buffalo home on September 10. He traveled to the Adirondacks to climb Mount Marcy, the highest peak in New York state, as part of a family vacation. The Vice President was staying at a cottage when he received word that McKinley had taken a turn for the worse. Deciding not to wait for daybreak, Roosevelt left the cottage at midnight. With the help of several wagon drivers, he traveled five hours to the nearest train station to board a train to Buffalo. It was at the train station that Roosevelt learned that McKinley was dead. About 13 hours after McKinley’s passing, Roosevelt privately took the oath of office at Wilcox’s house.

Roosevelt had to borrow formal clothes for the occasion, and he barred photographs of the ceremony. At the prompting of Secretary of War Elihu Root, Roosevelt took an oath administered by federal judge John Hazel.