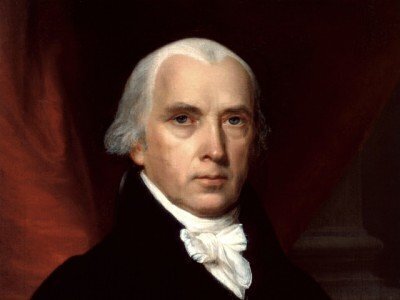

On June 8, 1789, James Madison addressed the House of Representatives and introduced a proposed Bill of Rights to the Constitution. More than three months later, Congress would finally agree on a final list of Rights to present to the states.

Some of Madison’s opening list of amendments didn’t make the final cut in September. The House agreed on a version of the Bill of Rights that had 17 amendments, and later, the Senate consolidated the list to 12 amendments. In the end, the states approved 10 of the 12 amendments in December 1791. One of two amendments rejected by the states was eventually ratified in 1992 as the 27th Amendment; it restricted the ability of Congress to change the pay of a sitting Congress while in session. (The other proposed amendment not ratified dealt with the number of representatives in Congress, based on the 1789 population.)

But if Madison had his original way, our Constitution would have a two-part Preamble that includes part of Thomas Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence before the current preamble.

On June 8, 1789, Madison told Congress the Preamble needed a “pre-Preamble.”

“First. That there be prefixed to the Constitution a declaration, that all power is originally vested in, and consequently derived from, the people. That Government is instituted and ought to be exercised for the benefit of the people; which consists in the enjoyment of life and liberty, with the right of acquiring and using property, and generally of pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety. That the people have an indubitable, unalienable, and indefeasible right to reform or change their Government, whenever it be found adverse or inadequate to the purposes of its institution.”

In essence, Madison wanted to bury arguably the most famous sentence in American history, “We the People,” in the middle of a combined Preamble.

Roger Sherman of Connecticut was among the first to question the move to downplay “We the People.”

“The truth is better asserted than it can be by any words what so ever. The words ‘We the People’ in the original Constitution are as copious and expressive as possible,” he said. And in time, Congress deleted the entire “pre-Preamble” as the Bill of Rights went through committees.

Another item that Madison proposed was making sure at least three of the liberties guaranteed in the Bill of Rights applied to all states. “No State shall violate the equal rights of conscience, or the freedom of the press, or the trial by jury in criminal cases,” Madison said in the fifth part of his original Bill of Rights proposal. The selective incorporation of parts of the Bill of Rights to the states didn’t happen until the early part of the 20th century as the Supreme Court interpreted the 14th Amendment in a series of cases.

Madison also wanted to clearly spell out that each branch of government had clear, distinct roles.

“The powers delegated by this Constitution are appropriated to the departments to which they are respectively distributed: so that the Legislative Department shall never exercise the powers vested in the Executive or Judicial, nor the Executive exercise the powers vested in the Legislative or Judicial, nor the Judicial exercise the powers vested in the Legislative or Executive Departments,” he said in the last part of his proposed Bill of Rights.

Neither of these items made it through the congressional review process. But Madison felt strongly enough about the separation of powers clause that he wanted it as the new Article VII in the Constitution.

And the second part of the new “Article VII” did survive in the Bill of Rights. It became the Tenth Amendment: “The powers not delegated by this Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively.”

Another interesting twist in Madison’s proposed Bill of Rights was a different version of what became the Second Amendment.

“The right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed; a well armed and well regulated militia being the best security of a free country: but no person religiously scrupulous of bearing arms shall be compelled to render military service in person,” said Madison.

And the final, big difference that Madison wanted was the entire Bill of Rights interwoven within the Constitution, and not appended at the document’s end.

That idea didn’t pass muster with Congress because there were concerns of an appearance that the Constitution was being rewritten. Madison dropped his support of “interweaving” the amendments during the House debate about moving his already amended Bill of Rights to the Senate. In the end, many core ideas introduced by Madison in June 1789 made it into the ratified version of the Bill of Rights.

“I think we should obtain the confidence of our fellow citizens, in proportion as we fortify the rights of the people against the encroachments of the government,” Madison said in his address to Congress in June 1789.