It was on this day in 1789 that the federal government started to operate under the terms of the U.S. Constitution, as the Confederation Congress ceded power. However, there was a major problem with the first session of the new Congress: not enough members showed up.

The significance of March 4th predates the Constitution. The Confederation Congress, which operated under the Articles of Confederation (our first Constitution) picked March 4, 1789, as the day it handed off power to the new constitutional government.

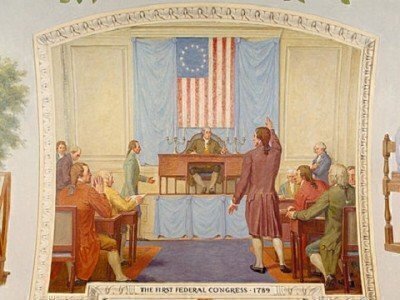

March 4th was the Constitution’s first official day in business. The first modern Congress convened in New York City at Federal Hall. It was about one month before George Washington was elected as the first President under the new Constitution.

Of its 81 members, only 22 showed up for the first session. The House selected Frederick Muhlenberg of Pennsylvania as its Speaker. But it would take another month for enough members to arrive in New York to start the 1st Congress and form a quorum to vote. By September 1789, Congress had agreed on a version of the Bill of Rights to present to the states for ratification. That happened two years later.

Congress moved its first day of business after that to December 1st, in accordance with Article I, Section 4, of the Constitution, which says that “the Congress shall assemble at least once in every year, and such meeting shall be on the first Monday in December unless they shall by law appoint a different day.”

The 3rd Congress started meeting on December 1st, but March 4th was reserved for a special role in every Congress. It was picked as the last day of its two-year session. (The Constitution didn’t mandate an ending date for a Congress.)

Logistically, the arrangement created problems. After a November election, defeated Congress members would still need to serve in session from December 1st to March 4th of the following year, in a very extended “lame duck” session.

The same lame-duck Congress also had responsibilities under the Constitution for conducting any business related to the election of the president and vice president, if needed.

Likewise, a newly elected president was inaugurated on March 4th as a new Congress was seated. The combination of a lame-duck president and Congress could have serious implications. For example, after Abraham Lincoln’s election in 1860, lame-duck President James Buchanan and a divided Congress saw seven southern states leave the Union until Lincoln took over on March 4, 1861.

Lame-duck House sessions also elected Thomas Jefferson and John Quincy Adams as president in two races that were sent to the House in 1800 and 1824.

Another point of contention was the exact time on March 4th that a congressional session ended.

A spat in 1851 started by a senator from Mississippi, Jefferson Davis, led to a Senate resolution marking 11:59 a.m. on March 4th as the end of a Congress and 12 p.m. as the start of a new Congress. (The House, as a habit, didn’t meet on March 4th at the time.)

Before then, some people considered the stroke of Midnight on March 3rd as the end of Congress’s two-year term.

The Senate’s website describes a regular scene where the Senate doorkeeper would move the minute hand on the chamber’s official clock as members debated about time.

The drama over March 4th every year ended when the 20th Amendment was ratified in 1933. Part of the amendment eliminated an extended lame-duck Congress. The new amendment set January 3rd as the starting day of a new Congress and January 20th as inauguration day for the president. The previous congressional and presidential terms ended just before the new terms began.

But not to be forgotten are some other March 4th events, such as President Lincoln’s two inaugural addresses and President Franklin Roosevelt’s address in 1933. One infamous inaugural was on March 4, 1829, when President Andrew Jackson's supporters stormed the White House and had to be lured away with the promise of free liquor.