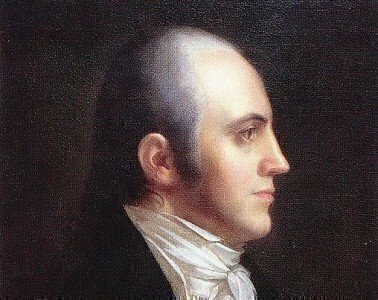

How did the Senate get the filibuster? The unique procedure may have been created thanks to some comments made by Aaron Burr.

The filibuster in its original American form dates back to the Burr era and it allows a Senator (or a group of Senators) to delay a vote on procedures, under certain circumstances. After two recent rules changes, the filibuster can only be used to stall votes about legislation.

The filibuster in its original American form dates back to the Burr era and it allows a Senator (or a group of Senators) to delay a vote on procedures, under certain circumstances. After two recent rules changes, the filibuster can only be used to stall votes about legislation.

The old-school “talking filibuster” is rare today. Like actor Jimmy Stewart in the film “Mr. Smith Goes To Washington,” a Senator can speak continuously—sometimes off-the-cuff, other times, reading from a phone book—in a public protest about a vote. The modern version is called a “silent filibuster.” This happens when a Senator tells his or her floor leader that they wish to filibuster a vote. At that point, at least 60 senators have to agree to override the filibuster in what is called a cloture vote.

These kind of delaying tactics aren’t exactly new. One of the first recorded masters of the filibuster was the ancient Roman politician Cato the Younger. In Rome’s senate, Cato would speak until sunset, which was the official ending of a Senate session. One of his last filibusters was to oppose Julius Caesar’s return to Rome in 60 B.C. Caesar found a political way around Cato’s filibuster and was able to grab power in Rome anyway.

In an article in The Atlantic, authors Rob Goodman and Jimmy Soni said that Rome’s problems with filibusters weren’t lost on the Founding Fathers, which is why the filibuster isn’t spelled out in the Constitution.

“Our Founders were deeply read in classical history, and they had good reason to fear the consequences of a legislature addicted to minority rule,” they said. “As Alexander Hamilton wrote in Federalist 22, ‘If a pertinacious minority can control the opinion of a majority ... [the government's] situation must always savor of weakness, sometimes border upon anarchy.’”

Ironically, Burr, Hamilton’s long-time rival, has gotten some credit as the father of the American filibuster. Political scientist Sarah Binder testified before the Senate in 2010 about how Vice President Burr told the Senate in 1805 that it should eliminate a rule that automatically cut off floor debate, called the previous question motion because he thought it wasn’t needed.

“So when Aaron Burr said ‘get rid of the previous question motion,’ the Senate didn’t think twice. When they met in 1806, they dropped the motion from the Senate rule book,” she said. It was then-Senator John Quincy Adams who reminded his colleagues of Burr’s suggestion.

It still took three decades for the Senate to realize it could actually filibuster a motion, but it was Burr’s comments that made it possible.

“The history of extended debate in the Senate belies the received wisdom that the filibuster was an original, Constitutional feature of the Senate. The filibuster is more accurately viewed as the unanticipated consequence of an early change to Senate rules,” she said.

Some scholars point to a Senate incident involving Henry Clay and Thomas Hart Benton in 1841 as the first modern filibuster moment. But legal scholars Catherine Fisk and Erwin Chemerinsky, in a law review article from 1997, took a close look at delaying tactics that dated back to Burr’s time.

In 1790, Senators from Virginia and South Carolina tried to use extended speeches in an attempt to block a Senate vote that approved the temporary location of Congress in Philadelphia. The previous motion tactic was on the books back then, said Fisk and Chemerinsky, but it was rarely used.

The 1841 Senate dispute between the Whigs, led by Clay, and the Democrats, led by Benton and John C. Calhoun, was about patronage positions. The delaying speeches by the Democrats lasted 10 days, but the Whigs, in the majority, prevailed.

The word filibuster came into use a decade later, to describe these “dilatory” efforts. It is based on a Dutch word for a type of pirate. In 1856, the Senate officially added a rule that allowed for unlimited debate in certain situations.

As a footnote, the House of Representatives had the filibuster for about two decades. There was a noteworthy filibuster in 1820 mounted by John Randolph to delay the Missouri Compromise. But in 1842, the House eliminated its filibuster. Among those objecting to the move was John Quincy Adams.

Scott Bomboy is the editor in chief of the National Constitution Center.