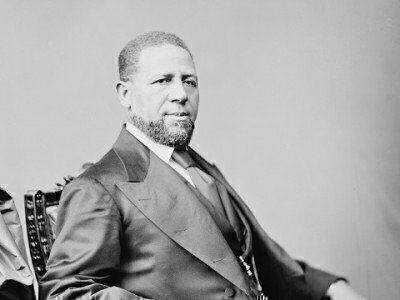

On this day in 1870, an African American politician was seated in the United States Senate for the first time, but only after Republican leaders rebuffed a challenge based on the infamous Dred Scott decision.

Hiram Rhodes Revels’s path to the Senate floor took him through numerous states as a freed Black man born in North Carolina, schooled in Indiana and Ohio, and as a preacher and educator in Kansas, Kentucky, and Tennessee.

Revels also served in the Civil War as a chaplain and he was at the battles of Vicksburg and Jackson in Mississippi. After the war, he settled in Natchez, Mississippi, continuing his educational and religious works. But Revels slowly became involved in politics, first as a local alderman in 1868, and then as a member of the Mississippi state senate in the state’s Reconstruction-era government in 1869.

Revels caught the attention of leaders in the state Senate after he gave an inspirational prayer to open a session in January 1870. That session soon turned to the serious business of electing two U.S. Senators from Mississippi, to be sent to Washington after Mississippi was readmitted as a state in the Union. (In that era, state legislatures elected U.S. Senators until the 17th Amendment went into effect.)

Seen as a moderate and as an educated man, Revels was put up for nomination and elected to the U.S. Senate by an 81 to 15 vote. He would fill the unexpired term of a Senator who quit in 1861, which ended in March 1871.

However, when Revels arrived in Washington in late January 1870, it was clear he would have opposition from people who objected to a Black person serving in the U.S. Senate. There were still a handful of Southern Democrats in Congress and they raised several barriers.

The first argument was that a Senate candidate had to be a United States citizen for at least nine years before assuming office. This logic pointed to the Supreme Court’s controversial Dred Scott decision from 1857, which was interpreted to state that Blacks of African American ancestry weren’t American citizens and that Revels had only been a citizen since the 14th Amendment was ratified in 1868.

Another argument was that Mississippi was still under military rule and a civilian government needed to confirm Revel’s election. The issue came to a head on February 23, 1871, when Mississippi was officially admitted back into the Union, and a floor vote came up to seat Revels in the Senate.

After two days of debate, the vote came to seat Revels. In an account from the New York Times, the historic nature of the moment was apparent.

“Mr. Revels, the colored Senator from Mississippi, was sworn in and admitted to his seat this afternoon at 4:40 o'clock. There was not an inch of standing or sitting room in the galleries, so densely were they packed; and to say that the interest was intense gives but a faint idea of the feeling which prevailed throughout the entire proceeding,” the Times said.

Republicans cut off objections from the southern Democrats, and the vote was 48-8 to let Revels take his Senate seat.

“The ceremony was short. Mr. Revels showed no embarrassment whatever, and his demeanor was as dignified as could be expected under the circumstances. The abuse which had been poured upon him and on his race during the last two days might well have shaken the nerves of any one,” the Times said.

Three weeks later, Revels gave his first speech to a packed Senate gallery about fears that Georgia would forbid African Americans from holding public office using language that was part of its deal to gain admittance back to the Union.

“I remarked that I rose to plead for protection for the defenseless race that now sends their delegation to the seat of Government to sue for that which this Congress alone can secure to them. And here let me say further, that the people of the North owe to the colored race a deep obligation that is no easy matter to fulfill,” he said.

In his brief Senate career, Revels was seen as a moderate who opposed segregation and supported civil rights, but he also wanted amnesty for former Confederate soldiers. Revels chose not to seek more time in the Senate, and he left Washington in March 1871 to become the first president of what became Alcorn University, the first land grant school for African Americans in the United States.

Revels remained active in the religious and educational communities for the rest of his life. He died on January 16, 1901, as he was attending a religious conference.

In 1875, Blanche Kelso Bruce, also of Mississippi and of African American descent, was elected to the Senate and served a full six-year term.

It would be another 92 years until Edward Brooke of Massachusetts became the third black to win a seat in the U.S. Senate.