National Constitution Center content fellow Trey Sullivan takes a look at the complicated relationship between William Lloyd Garrison and Frederick Douglass, and their acutely different perspectives on the place of the Constitution in our society.

Standing before an enraptured crowd at the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society’s Independence Day celebration in 1854, William Lloyd Garrison––the Society’s founder and one of the nation’s leading white abolitionists––brandished a copy of the U.S. Constitution. Yet this was to be no hagiography of the Founders’ work; rather, echoing the fiery rhetoric of the Old Testament, Garrison labeled the Constitution “a covenant with death” and “an agreement with hell.”

Standing before an enraptured crowd at the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society’s Independence Day celebration in 1854, William Lloyd Garrison––the Society’s founder and one of the nation’s leading white abolitionists––brandished a copy of the U.S. Constitution. Yet this was to be no hagiography of the Founders’ work; rather, echoing the fiery rhetoric of the Old Testament, Garrison labeled the Constitution “a covenant with death” and “an agreement with hell.”

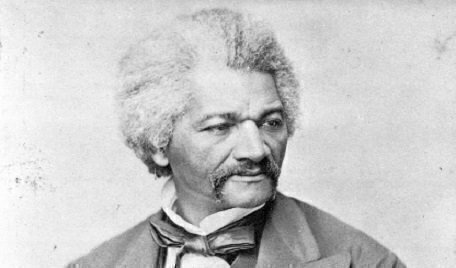

His words rang in stark opposition to the position taken by Frederick Douglass two years prior. In his famous “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July” Speech, Douglass emphasized the emancipatory potential of the Constitution, calling it “a GLORIOUS LIBERTY DOCUMENT.”

Ironically, the two men, whose constitutional interpretation came to embody rival flanks within the American abolitionist movement, were once political allies and close friends. Douglass began his career as Garrison’s most able protégée––traveling to cities within the Garrisonian abolitionist circuit to share the horrors of slavery.

However, as Douglass matured, he chafed under Garrison’s demands for ideological conformity and his paternalistic attitude. The relationship began to sour in the late 1840s, when Douglass left Garrison’s Liberator newspaper to start his own publication, The North Star.

Yet it was their acutely different perspectives on the place of the Constitution within the abolitionist movement that caused the ultimate schism. While Garrison believed that the Constitution wove racism into the fabric of American government and could only be countered with moralistic appeals to the body politic, Douglass held that the Constitution could be used as a tool to achieve racial justice. In a subsequent address, Douglass described the nation as a ship, with the Constitution as its compass––while the American vessel may be led astray through the governance of “mean, sordid, and wicked” men, the constitutional compass remained steadfastly pointed towards justice.

This dispute, legislated on the front pages of their respective newspapers, resulted in what historian David Blight termed Douglass’s “excommunication” from “the orthodoxy of the Garrisonian church.”

In life, the two men never fully reconciled; but is it possible, as we approach the semi quincentennial and reflect on our founding charter, to harmonize the discordant perspectives of these two prolific activists? Is it possible for the Constitution to be both glorious and hellish? And if so, how might “We the People” ensure the former and protect against the latter?

The Crowd vs. The Mob

W.E.B. Du Bois’s 1920 book Darkwater might help us mediate these two extremes. Written against the backdrop of 1919’s Red Summer, in which white vigilante mobs descended on Black communities across the country and murdered innocent civilians, Du Bois––like Douglass and Garrison before him––questioned whether the moral rot of racism could ever be excised from American politics. Put simply: was the anti-Black (or really, anti-Other) mob endemic to the American project or could another political paradigm be found to redeem the nation?

His search for a way up from this “nadir” in American race relations led Du Bois to identify what political philosopher Robert Gooding-Williams describes as two distinct expressions of group politics: the Mob vs. the Crowd.

To Du Bois’s readers, the word “mob” would immediately connote the southern lynch mob––lawless, violent, and spontaneous. But Du Bois complicates this easy association between the Mob and a brutish or “backcountry” southern mentality. For Du Bois, the freneticism of the Mob is premised on a much more stable ideology: the politics of exclusion.

To defeat the Mob, he writes, “we must get rid of the fascination for exclusiveness” and eliminate the “fiction of the Elect and the Superior.” Thus, the defining feature of Du Bois’s mob is not its comportment, but its composition. A civil, or even genteel, mob is still a mob if it is premised on the exclusion and subjection of the “other.” Put another way, the Supreme Court in Plessy v. Ferguson expressed the same mob mentality as the 1919 rioters. The latter might map more easily onto our conceptions of a “mob,” but Du Bois emphasizes that neither etiquette nor proceduralism absolves exclusionary behavior.

In contradistinction to the Mob, the Du Boisian Crowd sees heterodoxy as its strength and acts out of a conviction that is, at once, deliberative and impassioned. Gooding-Williams articulates that the Crowd is “marked by a receptivity to the unfamiliar possibilities and dispositions that the group’s strangers represent.”

In other words, the Crowd is defined by its willingness to include the marginalized and uplift the voice of the “other” within the political process. Importantly, this expansive politics is not just for the benefit of those targeted by the Mob; rather, in embracing a Crowd-politics, we allow for the flourishing of humankind’s “infinite possibilities” ––to the shared benefit of the whole society. The Crowd allows us to “discover each other” and see in the “stranger,” a collaborator in the national project.

The Constitution is a revolutionary document: establishing, for the first time in modern history, a nation founded on the absolute sovereignty of the people. The question has always been: are these privileges and protections shared freely amongst the Crowd or hoarded by the Mob? Are we to be a herrenvolk or a participatory democracy?

Thus, understood through the lens of Crowd politics, the Constitution is a “glorious liberty document”; yet when authority is ceded to the interest of the Mob, the Constitution does portend death––both political, and often literal––for the marginalized.

The Mob and The Crowd at 250

In 1790, James Wilson, an oft-forgotten but essential architect of the Constitution, gave a series of “Lectures on Law” at the University of Pennsylvania. There, he articulated that, for “We the People” the Constitution is “as clay in the hands of a potter.” Understanding that they did not have a monopoly over constitutional wisdom, Wilson and his peers left it to future generations to “preserve, to improve, [and] to refine” the document. And while many Founders could not imagine a multiracial democracy, courageous Americans throughout our nation’s history have taken this fractured clay and molded it toward a more just Union.

Through the Reconstruction Amendments, the 19th Amendment, the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and countless other nudges towards equality, women and men have fought against the political violence of the Mob. But progress is not a foregone conclusion––the same document that now guarantees minority political rights was once used by the Taney Court and its pro-slavery supporters to classify Black Americans as property. And ongoing debates over the Constitution’s text and history further evince the contingency of the document.

One could frame the Constitution’s ambivalent nature as a failure of the Founders to decisively resolve important constitutional questions, but one could also choose to see it as a testament to the vital role that “We the People” are called to play in the maintenance of our democracy. The Constitution is not self-actualizing––neither for equality nor for exclusion.

Madison writes in Federalist 48 that “parchment barriers” alone are defenseless against “the encroaching spirit of power”; similarly, while John Adams appreciated the ingenuity of the Constitution, he maintained that it was only viable in the hands of “a moral and religious people.” Most tangibly, the Founders at the Convention ensured that “We the People” would have the power to perpetually rewrite our national framework through the Article V amendment process. On this regard, the Founders were clear: the people, not ink and paper, imbue the Constitution with its ethos and authority. Consequently, we decide whether to use the Constitution to advance a Crowd- or Mob-politics.

Seeking inspiration in the Constitution’s text and principles

As we approach our 250th anniversary, we should take this responsibility seriously. We need not subscribe to all of the Founders’ specific views. But we should still seek inspiration in the Constitution’s text and principles, which invite us to aspire to the civic ideals of active, engaged, and informed citizenship––ideals championed by the Founders at the Convention and through the ratification process, even as they failed to extend the full promise of those principles to many Americans in their own time. If we want the Constitution to support the vitality of the Crowd, our public servants must seek to apply the privileges of the Constitution to all citizens––regardless of race, sex, ethnicity, or religion.

While Douglass and Garrison never rekindled their once-deep friendship, Douglass respected Garrison’s commitment to racial justice; and when Garrison died in 1879, Douglass was chosen to eulogize him. In the address, Douglass reflected on the herculean task Garrison had undertaken in challenging the “mighty system of slavery,” which had metastasized such that it infected every institution in America––the Church, the government, the economy. Most importantly, Douglass articulated that the system had “forced itself into the Constitution.” Yet while well-meaning, Douglass mistakenly removes the central role of human agents in bending the Constitution towards human bondage. Slavery did not force itself into our founding charter, people put it there; and likewise, people removed it. At both its zenith and nadir, the Constitution is animated by human action.

Put simply, whether we rise to the limitless possibilities of the Crowd or succumb to the Mob is entirely in our hands. It is both a hellish task and a glorious inheritance.

Trey Sullivan is a Content Fellow at the National Constitution Center and a PhD candidate in History at the University of Cambridge, where he is a Marshall Scholar.