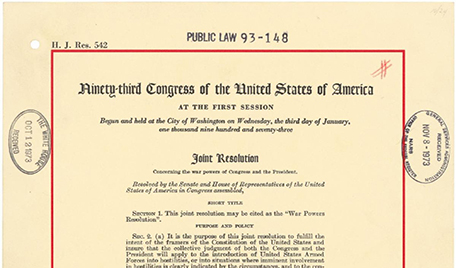

In the coming weeks, the debate about the constitutional legitimacy of recent actions taken by the United States against Venezuela will continue as Congress considers restraining the Trump administration’s powers under a 1973 statute, the War Powers Resolution.

On Jan. 3, 2026, United States military forces captured Venezuela’s president, Nicolas Maduro, and his wife, Cilia Flores, in Caracas, and removed them to the United States to stand trial. Maduro and Flores face an indictment on narco-terrorism, cocaine-importation, and weapons charges in the United States District Court Southern District of New York. On Monday, they pleaded not guilty to the charges.

On Jan. 3, 2026, United States military forces captured Venezuela’s president, Nicolas Maduro, and his wife, Cilia Flores, in Caracas, and removed them to the United States to stand trial. Maduro and Flores face an indictment on narco-terrorism, cocaine-importation, and weapons charges in the United States District Court Southern District of New York. On Monday, they pleaded not guilty to the charges.

The military operation to capture Maduro and Flores is the latest in a series of actions taken by the United States against Venezuela, including a blockade of oil tankers and attacks on boats that the United States alleged were trafficking drugs.

In December 2025, Congress debated passing resolutions about military actions related to Venezuela. On Dec. 17, 2025, two votes in the House failed by narrow margins to require President Donald Trump to notify Congress in advance of any military actions taken against Venezuela. The Senate rejected a similar resolution by two votes.

In the aftermath of the actions against Maduro and Flores, some Senate leaders want a new joint resolution presented to Congress restricting military actvivties against Venezuela, citing the War Powers Resolution of 1973.

The War Powers Resolution Explained

The War Powers Resolution is rooted in military conflicts after World War II. Article I, Section 8, Clause 11 of the Constitution grants the power to declare war to Congress. As noted in the National Constitution Center’s Interactive Constitution, scholars Michael Ramsey and Steve Vladeck state the Declare War Clause “unquestionably gives the legislature the power to initiate hostilities. The extent to which this clause limits the president’s ability to use military force without Congress’s affirmative approval remains highly contested.”

Congress has not approved formal war declarations since it took action against Bulgaria, Hungary and Rumania on June 4, 1942, following earlier declarations against Japan, Germany, and Italy in late 1941. The United States military involvement in Korea came as part of a United Nations effort, while the escalation of the Vietnam War followed a joint resolution passed by Congress as requested by President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1964.

In recent years, the debate over U.S. military interventions has focused on the War Powers Resolution statute and another clause of the Constitution. Article II of the Constitution spells out that “the president shall be commander in chief of the Army and Navy of the United States, and of the militia of the several states.”

The War Powers Resolution, passed by Congress in 1973 over President Richard Nixon's veto, requires that in the absence of a declaration of war passed by Congress, a president must report to Congress within 48 hours after introducing military forces into hostilities and must end the use of such forces within 60 days unless Congress permits otherwise. In his veto message, Nixon wrote the Resolution statute “would attempt to take away, by a mere legislative act, authorities which the president has properly exercised under the Constitution for almost 200 years. …The only way in which the constitutional powers of a branch of the Government can be altered is by amending the Constitution.”

The War Powers Resolution requires the president “in every possible instance” to consult with Congress before introducing the military into imminent hostilities and provides the ability for Congress to terminate the use of force used in unauthorized hostilities at any time by concurrent resolution of the House and Senate.

Debates Over the Use of Military Force in Recent Years

Since 1973, presidents have dealt with the War Powers Resolution in several ways. As of 2017, presidents had filed 168 reports to Congress related to the statute. But they also have taken military actions without preauthorization from Congress, citing inherent Article II powers or authorizations approved by Congress in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks on the United States. According to the Reiss Center on Law and Security at New York University, of 128 reports filed to Congress by the president 48 hours after a military action, 126 cite Article II as the domestic legal authority for the president's actions.

In addition to the Commander in Chief Clause, the president is presumed to have extensive powers over the conduct of foreign affairs. In United States v. Curtiss-Wright Export Corporation (1936), the Supreme Court upheld an arms embargo issued by President Franklin Roosevelt and found that “the president is the sole organ of the nation in its external relations, and its sole representative with foreign nations.”

In 1993, President Bill Clinton ordered U.S. military forces to take part in NATO activities in Bosnia-Herzegovina citing his “constitutional authority to conduct U.S. foreign relations” as commander in chief.

In 2011, President Barack Obama authorized U.S. military operations in Libya, taking the position his actions in Libya were not “hostilities” under the language of the War Powers Resolution and the United States was not in a “war” in Libya under of Article I. In 2013, President Obama asked Congress to approve intervention in the Syrian civil war, after he initially indicated he had the constitutional powers to order limited military strikes without its approval. Congress then declined to act in Syria.

In 2018, President Trump ordered airstrikes against chemical weapons facilities in Syria and, in 2020, an airstrike in Iraq that killed Qasem Soleimani, the leader of Iran’s Revolutionary Guards. Trump cited an authorization for the use of military force (AUMF) issued 2002 during Bush administration, and his Commander in Chief authority, as supporting the air strikes.

In 2021, President Joseph Biden cited the AUMF of 2002 and his Article II powers in taking military actions against Iran-backed militant groups in Iraq, Syria, and Yemen. President Biden filed reports to Congress with the caveat he was acting “pursuant to my constitutional authority as Commander in Chief and Chief Executive and to conduct United States foreign relations.”

In June 2025, the United States attacked three nuclear facilities in Iran during that nation’s conflict with Israel. A resolution sponsored by Sen. Tim Kaine of Virginia requiring President Trump to ask for congressional permission to continue military actions in Iran failed to advance from the Senate. President Trump submitted a War Powers Resolution report to Congress, claiming powers based on his role “as Commander in Chief” and “pursuant to constitutional authority to conduct United States foreign relations.”

Kaine and other Senate leaders have said they will introduce a resolution soon requiring Congress to approve more military actions from the Trump administration against Venezuela. If the Senate and House pass the resolution by a simple majority, it still faces a likely presidential veto. In a similar scenario, Congress approved a resolution in May 2020 limiting President Trump’s ability to act against Iran without congressional consent. The Senate failed to override the veto in a 49-44 vote, falling far short of the two-thirds majority needed to sustain the resolution.

So, while War Powers Resolution might apply to the current situation in Venezuela, the bar of a presidential veto is a considerable constitutional factor difficult to overcome. And the basic constitutional questions about the War Powers Resolution’s context related to the president’s Article II powers will continue to be debated.

Scott Bomboy is the editor in chief of the National Constitution Center.