The Tea Party protests of 1773 were undoubtedly a turning point in American history, but does Philadelphia have a rightful claim on being the starting point of the colonial movement?

On October 16, 1773, a group of Philadelphia patriots decided to tell the British crown that it would mount a boycott of tea, months before a similar act in Boston. The violent protests in Boston Harbor were met with a direct response from Great Britain, while a Philadelphia non-violent protest sent a British tea ship away without direct retribution.

The publication of a document called Philadelphia Resolutions triggered public protests in the two cities, and the protests would lead to the eventual armed clash between colonists and the British government forces, and the American War of Independence.

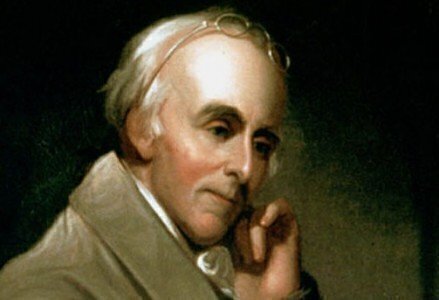

In later years, Dr. Benjamin Rush, who helped draft the Philadelphia Resolutions, reminded John Adams that Adams himself has said the revolution had its origins in actions taken by Philadelphians.

“I once heard you say [that] the active business of the American Revolution began in Philadelphia in the act of her citizens sending back the tea ship, and that Massachusetts would have received her portion of the tea had not our example encouraged her to expect union and support in destroying,” Rush told Adams in a letter. “The flame kindled on that Day [October 16, 1773] soon extended to Boston and gradually spread throughout the whole continent.”

Rush's chronology would be appeared to be confused, since the Boston Tea Party occurred before Philadelphia turned back a much-bigger tea shipment, but the impact of the Philadelphia Resolutions can't be discounted.

The Philadelphia Resolutions appeared in Benjamin Franklin’s Pennsylvania Gazette newspaper several days after the October 16 meeting at the Pennsylvania State House, which is today known as Independence Hall. It was a list of eight grievances against the British government. (Franklin was still in England, but he was also actively criticizing the British crackdown on the rights of its subjects in America.)

Link: Read The Philadelphia Resolutions

A group of men was associated with the Sons of Liberty drew up the list. The Sons of Liberty started nearly a decade earlier in Boston when it opposed attempts by the crown to tax colonists without representation in Parliament .

The Philadelphia group included prominent leaders such Rush, William Bradford, Thomas Mifflin and Dr. William Cadwalader. For years, Americans refused to buy British tea because it included a tax levied on drinkers, a thought that repulsed colonists who didn’t believe they should be taxed without a representative sitting in the British parliament to voice their concerns.

Instead, Americans bought tea smuggled into the colonies. But in May 1773, Parliament gave the East India Company a tea monopoly that also made British tea much cheaper than smuggled tea.

“The claim of parliament to tax America, is, in other words, a claim of right to levy contributions on us at pleasure,” the Resolutions said. “The duty, imposed by parliament upon tea landed in America, is a tax on the Americans, or levying contributions on them, without their consent.”

The Resolutions also made it clear that the group thought the money raised by the tea tax through the Townshend Acts would be used by the crown to eliminate local governments run by the colonies, and the group called on Americans to prevent “a violent attack upon the liberties of America” by stopping the unloading of tea shipments and any tea sales.

Three weeks later, a similar group met at Faneuil Hall in Boston and it adopted the Philadelphia Resolutions.

“That the sense of this town cannot be better expressed than in the words of certain judicious resolves, lately entered into by our worthy brethren, the citizens of Philadelphia,” the Boston group said.

In late December 1773, as seven ships laden with tea started to arrive in the colonies, one ship with 698 cases of tea attempted to land in Philadelphia but was turned back. A group of 6,000 Philadelphians met at the State House to discuss the situation, in what was the largest mass gathering in the colonies.

The group told the ship’s captain he would be tarred and feathered if he tried to deliver the tea; the ship was allowed to get supplies for a return voyage and sent on its way.

Up in Boston, a similar large gathering had turned violent two weeks earlier, when three ships arrived with 342 chests of tea. In what became known as the Boston Tea Party, a party of men dressed as Indians dumped the tea chest’s contents into Boston Harbor.

In April 1774, the British Parliament passed the Coercive (or Intolerable) Acts, which punished Massachusetts for the Tea Party incident. But other colonists, including Philadelphians, saw the acts as a punishment targeted at all the colonies.

At the same time, Franklin wrote a public letter in London, under an assumed name, that made it clear how he felt about Parliament, “who appear to be no better acquainted with their History or Constitution than they are with the Inhabitants of the Moon.”

“The Flame of Liberty in North America shall not be extinguished. Cruelty and Oppression and Revenge shall only serve as Oil to increase the Fire,” Franklin added.