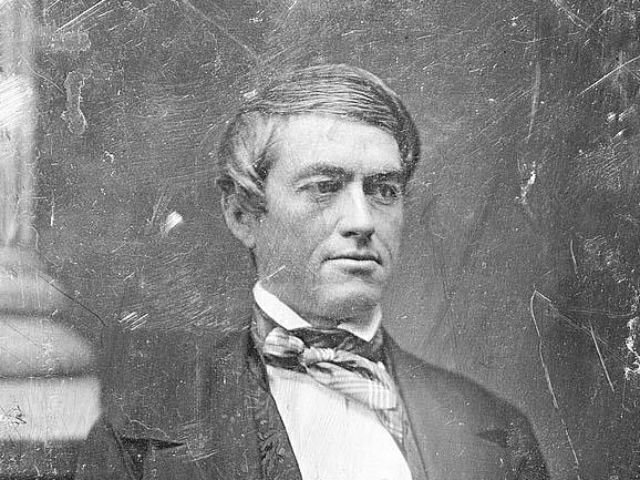

On October 19, 1810, Green Clay, cousin of former Senator Henry Clay, and Sally Lewis welcomed their son, Cassius Marcellus Clay, into the world. Little did they know how colorful a character their son would become.

On October 19, 1810, Green Clay, cousin of former Senator Henry Clay, and Sally Lewis welcomed their son, Cassius Marcellus Clay, into the world. Little did they know how colorful a character their son would become.

Clay—featured on the National Constitution Center’s American National Tree, part of its main exhibit—was born in Kentucky and resided there for most of his life. Although his family had owned slaves, Clay became an abolitionist early in his life after hearing a speech by William Lloyd Garrison while at Yale in 1832. He eventually founded the abolitionist newspaper True American.

In 1835, he was elected to the Kentucky House of Representatives, and was reelected three more times, despite his abolitionist beliefs. He was one of the first members of the Republican Party, eventually currying favor with President Lincoln.

While in the Kentucky House, Clay was not the most popular man. On two occasions, he was nearly killed for being an abolitionist. The first attempt occurred during a political debate. The story goes that political enforcer Sam Brown was hired to take Clay out; he walked on stage and promptly shot Clay in the chest. But Clay did not go down, and instead struck Brown multiple times with his Bowie knife, ultimately cutting off Brown’s nose and ear.

The second attempt was an ambush by the Turner brothers, whose father was a proslavery politician. They surrounded Clay and proceeded to beat and stab him to near death. But Clay, never one to go down without swinging, once again used his Bowie knife to injure his attackers, and eventually ran down the eldest brother, Clay Turner, and stabbed him to death, according to The Worst Case Scenario Almanac: Politics.

Despite his reputation for being a bruiser, Clay was also a skilled politician, although his most notable accomplishments happened abroad. He was appointed by Lincoln to be United States Ambassador to Russia. His tenure ran through the Civil War, and was critical in ensuring Russian support for the North during the war. The agreement was made as a preventive measure to discourage Britain and France from supporting the South, as the Russians deployed parts of their Navy in the harbors of New York and San Francisco in a show of support. He was also crucial in the talks that ultimately allowed the U.S. to buy Alaska from the Russians, which was ultimately completed shortly after the war, according to Cassius Marcellus Clay: A Firebrand of Freedom.

After his ambassadorship ended, Clay still sought to make his voice heard. He supported the Cuban Independence Movement against Spain, forming the Cuban Charitable Aid Society. Politically, Clay switched parties due to disagreements over certain policy issues, such as President Grant’s decision to interfere in Haiti and the Radical Republicans’ plans for Reconstruction. He instead joined the Liberal Republicans and later became a Democrat. But ultimately, Clay returned to the party of which he was one of the first members. Clay died in 1903 due to natural causes—ironic, considering all the attempts on his life.

Clay’s legacy still lives on at his estate, White Hall, which can be found in Richmond, Kentucky. Also, his name has been passed down for generations. One of his former slaves, Herman Heaton Clay, named his son Cassius Clay in honor of the abolitionist. That Cassius Clay then named his son Cassius Clay Jr., who would ultimately become the heavyweight champion of the world before changing his name to Muhammad Ali.

Chris Calabrese is an intern at the National Constitution Center. He is also a recent graduate of St. Joseph’s University.