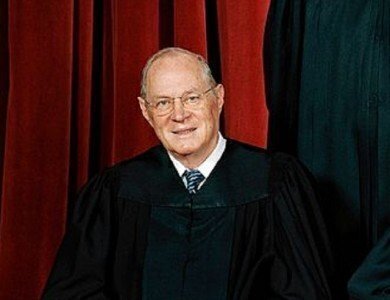

The Supreme Court arguments in the Fisher affirmative action case were contentious on Wednesday, and as anticipated, Justice Anthony Kennedy will likely be the deciding vote in a potential landmark decision.

Eight, and not nine, justices heard the arguments in round two of Fisher v. University of Texas on Wednesday morning. Justice Elena Kagan was recused due to her prior job as Solicitor General. Still, at least five Justices will need to vote to change a lower court’s decision to allow the university’s current affirmative action stand.

Eight, and not nine, justices heard the arguments in round two of Fisher v. University of Texas on Wednesday morning. Justice Elena Kagan was recused due to her prior job as Solicitor General. Still, at least five Justices will need to vote to change a lower court’s decision to allow the university’s current affirmative action stand.

Link: Read The Argument Transcript

Most observers saw three possible lines of actions, based on the long run-up to the arguments and some of the Justice’s comments.

“The case, it would appear, now comes down to three options: kill affirmative action nationwide as an experiment that can’t be made to work, kill just the way it is done at the Texas flagship university because it can’t be defended, or give the university one more chance to prove the need for its policy,” said Lyle Denniston on SCOTUSblog.

Denniston also pointed out that Kagan’s absence is a definite factor. “Because the first two options that seemed to emerge would be momentous rulings, it may be that the Court would not want to do either with only an eight-member Court,” he wrote on Wednesday.

All eyes and ears were on Kennedy, again as the probable swing vote in any decision. During some points, court observers believed Kennedy seemed to be considering remanding the case to a lower court, as it did in 2013 when the case was first argued in front of the Supreme Court.

But he then later told Gregory G. Garre, the university’s attorney, that the school “would not put in more evidence than we have now” for a lower court to reconsider the case – an argument Garre tried to refute.

In addition to Kennedy’s remarks, Justice Antonin Scalia raised a few eyebrows when he started to state arguments presented in briefs to the court about race and college admissions.

“One of the briefs pointed out that most of the black scientists in this country don’t come from schools like the University of Texas. They come from lesser schools where they do not feel that they’re being pushed ahead in classes that are too fast for them,” Scalia said. “I’m just not impressed by the fact the University of Texas may have fewer [blacks]. Maybe it ought to have fewer. I don’t think it stands to reason that it’s a good thing for the University of Texas to admit as many blacks as possible.”

Scalia was referring to what is called a “mismatch theory” related to affirmative action, a hotly debated topic. But in the end, Kennedy seemed to be frustrated with the overall case.

"We're just arguing the same case," Kennedy said. "It's as if nothing had happened."

In the case, former University of Texas applicant Abigail Fisher contends that the school’s discriminatory admission policies led to her rejection, even though her qualifications surpassed those of many admitted minority students.

The university maintains a program by which the top 10 percent of students in each public graduating class are granted automatic admission; Fisher argues that this is enough to ensure diversity. (She narrowly missed the cut at Stephen F. Austin High School, finishing 82nd out of 674.)

The U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals has twice agreed with the University of Texas policy, finding that that program makes limited use of race, and it conforms to the university’s intent to promote a racially and culturally diverse student body.

Fisher argues the 14th Amendment’s the Equal Protection Clause prohibits the school from considering race in any manner as part of the admissions process.