In the first part of a three-part series, Constitution Daily looks at a series of landmark cases that have defined free speech rights in the press and popular media, from the Colonial era until today. In part one, we look at controversies from the founding until the Civil War’s end.

The freedom of the press is one of the core rights enshrined in the Constitution’s First Amendment, as written in September 1787 and ratified in December 1791. As stated, “Congress shall make no law . . . abridging the freedom . . . of the press …”

The freedom of the press is one of the core rights enshrined in the Constitution’s First Amendment, as written in September 1787 and ratified in December 1791. As stated, “Congress shall make no law . . . abridging the freedom . . . of the press …”

The founders were very aware of the influence of printed words, and the important roles that newspaper and pamphlet publishers played in disseminating ideas. Prior to the era of the Revolutionary War and the Constitution, newspaper censorship became an issue in the colony of New York.

On August 4, 1735, in Crown v. Zenger, publisher John Peter Zenger faced seditious libel charges for printing an article that criticized New York’s colonial governor. A judge told a jury to only consider if Zenger printed the statements, and not their truthfulness. Instead, the jury returned with a not guilty verdict, believing the argument made by Zenger’s attorney, Andrew Hamilton, that the statements were truthful and could not be punished by the government.

Later, in 1798, Congress passed the Sedition Act, specifically targeted President John Adams’ opponents in the press, the Jeffersonian Republicans, and it was opposed by Vice President Thomas Jefferson and his key ally, James Madison. The Federalists sought to suppress dissent and criticism of the government, as a needed security measure, at a time when war with France seemed possible. The act punished the “writing, printing, uttering or publishing [of] any false, scandalous and malicious writing or writings about the government of the United States.”

In particular, Madison criticizes the act in the Virginia Resolutions as exerting a “power which more than any other ought to produce universal alarm, because it is levelled against that right of freely examining public characters and measures, and of free communication among the people thereon, which has ever been justly deemed, the only effectual guardian of every other right.”

Between 1798 and 1801, at least 26 people were tried in federal courts under the Sedition Act. In 1798, Vermont publisher Matthew Lyon, also a sitting member of the House of Representatives, was convicted of libel for publishing a letter that criticized President Adams. The Adams administration and his Federalist allies presented separate sedition charges to grand juries against editors Thomas Cooper and James Callendar, who had criticized the administration in print. Both men were convicted in jury trials presided over by Supreme Court Justice Samuel Chase, serving as circuit judge, and Cooper and James Callendar spent time in jail.

Another Hamilton Argues for Free Speech

After Thomas Jefferson became president in 1801, the federal Sedition Act expired. But prosecutions remained possible for seditious libel under state laws and the common law, since the First Amendment’s guarantees only applied to cases involving the federal government.

Harry Croswell, a young publisher in Hudson, New York, printed claims first made in the New York Evening Post that Thomas Jefferson had paid newspaper publisher Callendar to criticize George Washington and John Adams in a scandalous fashion. Among the accusations made by Callendar that appeared in the Evening Post and repeated by Crosswell were that Washington was “a traitor, a robber, and a perjurer” and that Adams was “a hoary-headed incendiary.” The Republicans, with Jefferson’s support, brought libel charges against Crosswell in state court. During a jury trial, Callendar was called as a witness but died in a drowning accident. The jury convicted Croswell of printing the statements, which constituted libel under the state law.

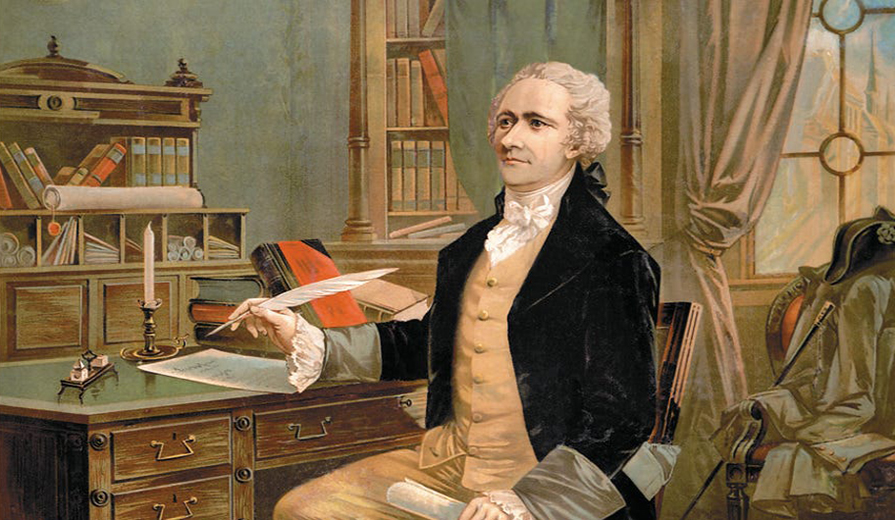

On appeal to the state Supreme Court, the Evening Post’s founder, Alexander Hamilton, argued Croswell’s case in People v. Croswell. “The right of giving the truth in evidence, in cases of libels, is all-important to the liberties of the people. Truth is an ingredient in the eternal order of things, in judging of the quality of acts,” Hamilton told the court during his six-hour-long argument.

Hamilton also stated two foundational principles of the free press: “The liberty of the press consists in the right to publish, with impunity, truth, with good motives, for justifiable ends, though reflecting on government, magistracy, or individuals,” and “[t]hat the allowance of this right is essential to the preservation of a free government; the disallowance of it fatal.”

While the court could not reach a verdict, Judge James Kent’s opinion expanded Hamilton’s reasoning, with Judge Kent calling Hamilton’s definition of liberty of the press “perfectly correct.” The New York state legislature soon made Hamilton and Kent’s arguments into law that the truth could be used as a defense against libel charges for printed materials.

Civil War Restrictions

During the Civil War era, the federal government argued that the First Amendment did not protect certain reporters and newspapers that criticized the war and the Lincoln administration, or reported on troop movements. In some cases, editors and publishers were jailed or banished from the United States. President Abraham Lincoln had used emergency war powers assumed by the president under the Constitution to place various restrictions on speech if such speech was deemed to benefit the Confederate cause.

According to the Free Speech Center at Middle Tennessee State University, Lincoln’s subordinates initiated free press restrictions with mixed results. General Ambrose Burnside issued the controversial General Order No. 38 in April 1863 in the Department of Ohio. The order read that “declaring sympathies for the enemy will no longer be tolerated in this department. … It must be distinctly understood that treason, expressed or implied, will not be tolerated in this department.”

The Chicago Times, Lincoln’s biggest critic in the region and a leading anti-war Democratic publication, pointed out that the order allowed Burnside to banish anyone from the United States without due process. Its editor also criticized Burnside’s war record. On June 1, 1863, Burnside issued General Order No. 84, closing the Chicago Times’ offices. It also banned the distribution of the New York World newspaper in the region.

On June 3, 1863, state lawmakers in the Illinois Democrat-controlled state house demanded the governor seek the order’s recission by federal authorities. “The order is in direct violation of the Constitution of the United States and of this State, and destructive to those God-given principles whose existence and recognition for centuries before a written constitution was made, have made them as much a part of our rights as the life which sustains us.” President Lincoln soon revoked General Order No. 84.

Scott Bomboy is the editor in chief of the National Constitution Center.