Historic Document

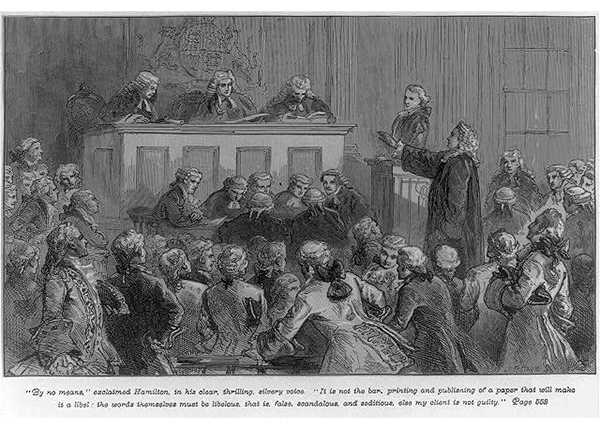

Argument in the Zenger Trial (1735)

John Peter Zenger | 1735

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Summary

The 1735 trial of John Peter Zenger later shaped the Founding generation’s commitment to a free press. In the 1730s, Zenger published an article criticizing the Royal Governor of New York for removing the colony’s Chief Justice. Prior to his removal, the Chief Justice had decided against the Governor in a recent case. From the perspective of modern First Amendment law, Zenger’s article was core political speech—speech criticizing the government. However, Zenger was tried for seditious libel, and, under British law at the time, truth was no defense to the charge. In other words, Zenger was guilty of seditious libel even if what he published about the Governor was true. In this excerpt, Zenger’s lawyer, Andrew Hamilton, argued to the jury that Zenger should not be punished for true statements criticizing the government. In the end, the jury agreed with Hamilton—ignoring the existing rule under the English common law and refusing to convict Zenger. This was an early example of jury nullification, with the jurors refusing to convict a guilty defendant (in this case, Zenger) for violating laws that the jurors deemed unjust. The case was so galvanizing that it came to stand for a core principle later enshrined by the Founding generation in the First Amendment—namely, that true statements criticizing the government cannot be punished.

Selected by

The National Constitution Center

Document Excerpt

May it please Your Honor, I was saying that notwithstanding all the duty and reverence claimed by Mr. Attorney to men in authority, they are not exempt from observing the rules of common justice, either in their private or public capacities; the laws of our Mother Country know no exemption. It is true, men in power are harder to become at for wrongs they do either to a private person or to the public; especially a governor in the plantations, where they insist upon an exemption from answering complaints of any kind in their own government. . . . But when the oppression is general there is no remedy even that way, no, our constitution has (blessed be God) given us an opportunity, if not to have such wrongs redressed, yet by our prudence and resolution we may in a great measure prevent the committing of such wrongs by making a governor sensible that it is his interest to be just to those under his care; for such is the sense that men in general (I mean freemen) have of common justice, that when they come to know that a chief magistrate abuses the power with which he is trusted for the good of the people, and is attempting to turn that very power against the innocent, whether of high or low degree, I say mankind in general seldom fail to interpose, and as far as they can, prevent the destruction of their fellow subjects. And has it not often been seen (and I hope it will always be seen) that when the representatives of a free people are by just representa¬tions or remonstrances made sensible of the sufferings of their fel¬low subjects by the abuse of power in the hands of a governor, they have declared (and loudly too) that they were not obliged by any law to support a governor who goes about to destroy a province or colony, or their privileges, which by His Majesty he was ap¬pointed, and by the law he is bound to protect and encourage. But I pray it may be considered of what use is this mighty privilege if every man that suffers must be silent? And if a man must be taken up as a libeler for telling his sufferings to his neighbor? . . . . .

[I]t is natural, it is a privilege, I will go farther, it is a right which all freemen claim, and are entitled to complain when they are hurt; they have a right publicly to remonstrate the abuses of power in the strongest terms, to put their neighbors upon their guard against the craft or open violence of men in authority, and to assert with courage the sense they have of the blessings of liberty, the value they put upon it, and their resolution at all hazards to preserve it as one of the greatest blessings heaven can bestow. . . . .

But to proceed; I beg leave to insist that the right of complaining or remonstrating is natural; and the restraint upon this natural right is the law only, and those restraints can only extend to what is false: For as it is truth alone which can excuse or justify any man for complaining of a bad administration, I as frankly agree that nothing ought to excuse a man who raises a false charge or accusation, even against a private person, and that no manner of allowance ought to be made to him who does so against a public magistrate. Truth ought to govern the whole affair of libels, and yet the party accused runs risk enough even then; for if he fails of proving every tittle of what he has wrote, and to the satisfaction of the Court and Jury too, he may find to his cost that when the prosecution is set on foot by men in power, it seldom wants friends to favor it. . . .

It is agreed upon by all men that this is a reign of liberty, and while men keep within the bounds of truth, I hope they may with safety both speak and write their sentiments of the conduct of men in power. I mean of that part of their conduct only which affects the liberty or property of the people under their administration; were this to be denied, then the next step may make them slaves: For what notions can be entertained of slavery beyond that of suffering the greatest injuries and oppressions without the liberty of complaining; or if they do, to be destroyed, body and estate, for so doing?

It is said and insisted on by Mr. Attorney, that government is a sacred thing; that it is to be supported and reverenced; it is government that protects our persons and estates; that prevents treasons, murders, robberies, riots, and all the train of evils that overturns kingdoms and states and ruins particular persons; and if those in the administration, especially the supreme magistrate, must have all their conduct censured by private men, government cannot subsist. This is called a licentiousness not to be tolerated. It is said, that it brings the rulers of the people into contempt, and their authority not to be regarded, and so in the end the laws cannot be put in execution. These I say, and such as these, are the general topics insisted upon by men in power and their advocates. But I wish it might be considered at the same time how often it has happened that the abuse of power has been the primary cause of these evils, and that it was the injustice and oppression of these great men which has commonly brought them into contempt with the people. The craft and art of such men is great, and who that is the least acquainted with history or law can be ignorant of the specious pre¬tenses which have often been made use of by men in power to in¬troduce arbitrary rule and destroy the liberties of a free people? . . . .

I only intend . . . to show that the people of England saw clearly the danger of trusting their liberties and properties to be tried, even by the greatest men in the kingdom, without the judgment of a jury of their equals. They had felt the terrible effects of leaving it to the judgment of these great men to say what was scandalous and seditious, false or ironical. And if the Parliament of England thought this power of judging was too great to be trusted with men of the first rank in the kingdom without the aid of a jury, how sacred soever their characters might be, and therefore restored to the people their original right of trial by juries, I hope to be excused for insisting that by the judgment of a Parliament, from whence no appeal lies, the jury are the proper judges of what is false at least, if not of what is scandalous and seditious. . . . I must say I cannot see why in our case the jury have not at least as good a right to say whether our newspapers are a libel or no libel as another jury has to say whether killing of a man is murder or manslaughter. . . .

Gentlemen; the danger is great in proportion to the mischief that may happen through our too great credulity. A proper confidence in a court is commendable; but as the verdict (whatever it is) will be yours, you ought to refer no part of your duty to the discretion of other persons. If you should be of opinion that there is no falsehood in Mr. Zenger’s papers, you will, nay (pardon me for the expression) you ought to say so; because you don’t know whether others (I mean the Court) may be of that opinion. It is your right to do so, and there is much depending upon your resolution as well as upon your integrity.

The loss of liberty to a generous mind is worse than death; and yet we know there have been those in all ages who for the sake of preferment or some imaginary honor have freely lent a helping hand to oppress, nay to destroy their country. . . . This is what every man (that values freedom) ought to consider: He should act by judgment and not by affection or self-interest; for, where those prevail, no ties of either country or kindred are regarded, as upon the other hand the man who loves his country prefers its liberty to all other considerations, well know¬ing that without liberty, life is a misery. . . .

Power may justly be compared to a great river, while kept within its due bounds, is both beautiful and useful; but when it overflows its banks, it is then too impetuous to be stemmed, it bears down all before it and brings destruction and desolation wherever it comes. If then this is the nature of power, let us at least do our duty, and like wise men (who value freedom) use our utmost care to support liberty, the only bulwark against lawless power, which in all ages has sacrificed to its wild lust and boundless ambition the blood of the best men that ever lived.

I hope to be pardoned, sir, for my zeal upon this occasion; it is an old and wise caution: That when our neighbor’s house is on fire, we ought to take care of our own. For though blessed be God, I live in a government where liberty is well understood and freely enjoyed; yet experience has shown us all (I’m sure it has to me) that a bad precedent in one government is soon set up for an authority in another; and therefore I cannot but think it mine and every honest man’s duty that (while we pay all due obedience to men in authority) we ought at the same time to be upon our guard against power wherever we apprehend that it may affect ourselves or our fellow subjects. . . .

But to conclude; the question before the Court and you gentlemen of the Jury is not of small nor private concern, it is not the cause of a poor printer, nor of New York alone, which you are now trying: No! It may in its consequence affect every freeman that lives under a British government on the main of America. It is the best cause. It is the cause of liberty; and I make no doubt but your upright conduct this day will not only entitle you to the love and esteem of your fellow citizens; but every man who prefers freedom to a life of slavery will bless and honor you as men who have baffled the attempt of tyranny; and by an impartial and uncorrupt verdict, have laid a noble foundation for securing to ourselves, our posterity, and our neighbors that to which nature and the laws of our country have given us a right—the liberty—both of exposing and opposing arbitrary power (in these parts of the world, at least) by speaking and writing truth.