Historic Document

Instructions to the Jury in the Quock Walker Case, Commonwealth of Massachusetts v. Nathaniel Jennison (1783)

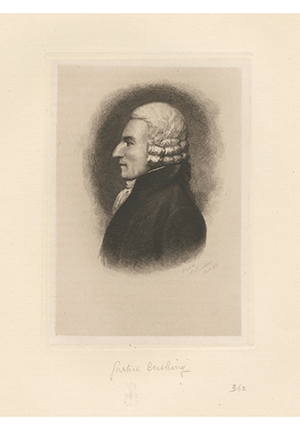

William Cushing | 1783

Emmet Collection of Manuscripts Etc. Relating to American History, The New York Public Library

Summary

Commonwealth v. Jennison was the last of three cases to decide the fate of Quock Walker, who legally challenged his enslavement on the grounds that it was inconsistent with the Massachusetts Constitution of 1780. In 1781, Walker had escaped from his alleged owner, Nathaniel Jennison, who then tracked him down and severely beat him. Walker filed suit against Jennison for assault and battery, and the legal struggle eventually made its way to the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts. In his instructions to the jury, Chief Justice William Cushing, who would later serve as one of the first justices on the United States Supreme Court, went much further than merely suggesting that Walker was entitled to his freedom—he declared that slavery itself was incompatible with the state’s constitution. The ruling in Walker’s favor was much discussed and helped bring a permanent end to the practice of slavery in Massachusetts. Later in 1808, in the case of Inhabitants of Winchendon v. Inhabitants of Hatfield, the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts declared that, “in the first action involving the right of master, which can be before the Supreme Judicial Court, after the establishment of the constitution, the judges declared, that, by virtue of the first article of the declaration of rights, slavery in this state was no more.”

Selected by

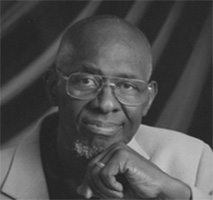

William B. Allen

Emeritus Dean of James Madison College and Emeritus Professor of Political Science at Michigan State University

Jonathan Gienapp

Associate Professor of History at Stanford University

Document Excerpt

Indenture Nathaniel Jennison found for an Assault of Body on Quock Walker [who he] beat with a stick and imprisoned two hours. …

Justification that Quock is a Slave—and to prove it tis said, that, Quock when child about nine months old with his father and mother were sold by bill of sale in 1754, about 29 years ago to Mr. Caldwell now deceased—That when he died, Quock was apprized as part of the personal estate and set off to the widow in her share of the personal estate; that Mr. Jennison marrying her was entitled to Quock as his property—and therefore that he had a right to bring him home when run away. And that the defendant only took proper measures for that purpose. And that the defendant’s council also rely on some former laws of the province, which give countenance to Slavery.

To this it is answered that if he ever was a Slave, he was liberated both by his Master Caldwell and by the Widow after his death, the first of whom promised and engaged, he should be free at 25—the other at 21.

As to the doctrine of slavery and the right of Christians to hold Africans in perpetual servitude, and sell and treat them as we do our horses and cattle, that (it is true) has been heretofore countenanced by the Province Laws formerly, but nowhere is it expressly enacted or established. It has been a usage—a usage which took its origin from the practice of some of the European nations, and the regulations of British government respecting the then Colonies, for the benefit of trade and wealth. But whatever sentiments have formerly prevailed in this particular or slid in upon us by the example of others, a different idea has taken place with the people of America, more favorable to the natural rights of mankind, and to that natural, innate desire of Liberty, with which Heaven (without regard to color, complexion, or shape of noses—features) has inspired all the human race. And upon this ground our Constitution of Government, by which the people of this Commonwealth have solemnly bound themselves, sets out with declaring that all men are born free and equal—and that every subject is entitled to liberty, and to have it guarded by the laws, as well as life and property—and in short is totally repugnant to the idea of being born slaves. This being the case, I think the idea of slavery is inconsistent with our own conduct and Constitution; and there can be no such thing as perpetual servitude of a rational creature, unless his liberty is forfeited by some criminal conduct or given up by personal consent or contract.