Historic Document

Commentaries on the Laws of England (1765-69)

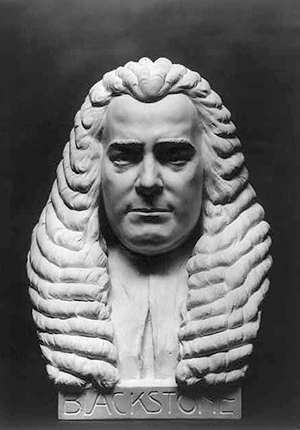

William Blackstone | 1765

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Divison

Summary

William Blackstone (1723-80) was the author of A Discourse on the Study of Law (1758), Commentaries on the Laws of England (1765-69), and other works. These works were for the most part based on lectures he delivered at the University of Oxford in and after the 1750s. Blackstone’s Commentaries, which owed an enormous debt to Locke’s Two Treatises of Government and to Montesquieu’s Spirit of the Laws, which he frequently cites and even more frequently paraphrases, quickly became the basis for legal education in America. Although, in the period stretching from 1760 to 1800, Blackstone was cited as an authority less often than Montesquieu, he was cited more often than Locke—especially, after 1776 when the Americans in their nascent states began engaging in constitution-making and a revision of their laws.

Selected by

Paul Rahe

Professor of History and Charles O. Lee and Louise K. Lee Chair in the Western Heritage at Hillsdale College

Jeffrey Rosen

President and CEO, National Constitution Center

Colleen A. Sheehan

Professor of Politics at the Arizona State University School of Civic and Economic Thought and Leadership

Document Excerpt

Introduction, Section the Second: “Of the Nature of Laws in General.”— This will of his maker is called the law of nature. For as God, when he created matter, and endued it with a principle of mobility, established certain rules for the perpetual direction of that motion; so, when he created man, and endued him with freewill to conduct himself in all parts of life, he laid down certain immutable laws of human nature, whereby that freewill is in some degree regulated and restrained, and gave him also the faculty of reason to discover the purport of those laws.

Considering the creator only as a being of infinite power, he was able unquestionably to have prescribed whatever laws he pleased to his creature, man, however unjust or severe. But as he is also a being of infinite wisdom, he has laid down only such laws as were founded in those relations of justice, that existed in the nature of things antecedent to any positive precept. These are the eternal, immutable laws of good and evil, to which the creator himself in all his dispensations conforms; and which he has enabled human reason to discover, so far as they are necessary for the conduct of human actions. Such among others are these principles: that we should live honestly, should hurt nobody, and should render to every one his due; to which three general precepts Justinian has reduced the whole doctrine of law. . . .

As therefore the creator is a being, not only of infinite power, and wisdom, but also of infinite goodness, he has been pleased so to contrive the constitution and frame of humanity, that we should want no other prompter to inquire after and pursue the rule of right, but only our own self-love, that universal principle of action. For he has so intimately connected, so inseparably interwoven the laws of eternal justice with the happiness of each individual, that the latter cannot be attained but by observing the former; and, if the former be punctually obeyed, it cannot but induce the latter. In consequence of which mutual connection of justice and human felicity, he has not perplexed the law of nature with a multitude of abstracted rules and precepts, referring merely to the fitness or unfitness of things, as some have vainly surmised; but has graciously reduced the rule of obedience to this one paternal precept, “that man should pursue his own true and substantial happiness.” This is the foundation of what we call ethics, or natural law. For the several articles into which it is branched in our systems, amount to no more than demonstrating, that this or that action tends to man’s real happiness, and therefore very justly concluding that the performance of it is a part of the law of nature; or, on the other hand, that this or that action is destructive of man’s real happiness, and therefore that the law of nature forbids it.

This law of nature, being coeval with mankind and dictated by God himself, is of course superior in obligation to any other. It is binding over all the globe in all countries, and at all times; no human laws are of any validity, if contrary to this: and such of them as are valid derive all their force, and all their authority, mediately or immediately, from this original.

But in order to apply this to the particular exigencies of each individual it is still necessary to have recourse to reason; whose office it is to discover, as was before observed, what the law of nature directs in every circumstance of life: by considering, what method will tend the most effectually to our own substantial happiness.

[T]hough society had not it’s formal beginning from any convention of individuals, actuated by their wants and their fears; yet it is the sense of their weakness and imperfection that keeps mankind together; that demonstrates the necessity of this union; and that therefore is the solid and natural foundation, as well as the cement, of society. And this is what we mean by the original contract of society; which, though perhaps in no instance it has ever been formally expressed at the first institution of a state, yet in nature and reason must always be understood and implied, in the very act of associating together: namely, that the whole should protect all it’s parts, and that every part should pay obedience to the will of the whole; or, in other words, that the community should guard the rights of each individual member, and that (in return for this protection) each individual should submit to the laws of the community; without which submission of all it was impossible that protection could be certainly extended to any. . . .

[T]here is and must be in all [the several forms of government] a supreme irresistible, absolute, uncontrolled authority, in which the jura summi imperii, or the rights of sovereignty, reside. . . .

[T]he constitutional government of this island is so admirably tempered and compounded, that nothing can endanger or hurt it, but destroying the equilibrium of power between one branch of the legislature and the rest. For if ever it should happen that the independence of any one of the three should be lost, or that it should become subservient to the views of either of the other two, there would soon be an end of our constitution. The legislature would be changed from that, which was originally set up by the general consent and fundamental act of the society; and such a change, however effected, is according to Mr Locke (who perhaps carries his theory too far) at once an entire dissolution of the bands of government; and the people would be reduced to a state of anarchy, with liberty to constitute to themselves a new legislative power.

Book the First: Of the Rights of Persons; Chapter the First: Of the Absolute Rights of Individuals—By the absolute rights of individuals we mean those which are so in their primary and strictest sense; such as would belong to their persons merely in a state of nature, and which every man is intitled to enjoy whether out of society or in it. . . . .

[T]he principal aim of society is to protect individuals in the enjoyment of those absolute rights, which were vested in them by the immutable laws of nature; but which could not be preserved in peace without that mutual assistance and intercourse, which is gained by the institution of friendly and social communities. Hence it follows, that the first and primary end of human laws is to maintain and regulate these absolute rights of individuals. Such rights as are social and relative result from, and are posterior to, the formation of states and societies: so that to maintain and regulate these is clearly a subsequent consideration. And therefore the principal view of human laws is, or ought always to be, to explain, protect, and enforce such rights as are absolute. . . .

[E]very man, when he enters into society, gives up a part of his natural liberty, as the price of so valuable a purchase; and in consideration of receiving the advantages of mutual commerce, obliges himself to conform to those laws, which the community has thought proper to establish. And this species of legal obedience and conformity is infinitely more desirable, than that wild and savage liberty which is sacrificed to obtain it. For no man, that considers a moment, would wish to retain the absolute and uncontroled power of doing whatever he pleases; the consequence of which is, that every other man would also have the same power; and then there would be no security to individuals in any of the enjoyments of life. Political therefore, or civil, liberty, which is that of a member of society, is no other than natural liberty so far restrained by human laws (and no farther) as is necessary and expedient for the general advantage of the publick. . . .

[L]aws, when prudently framed, are by no means subversive but rather introductive of liberty; for (as Mr Locke has well observed) where there is no law, there is no freedom. But then, on the other hand, that constitution or frame of government, that system of laws, is alone calculated to maintain civil liberty, which leaves the subject entire master of his own conduct, except in those points wherein the public good requires some direction or restraint. . . .

Thus much for the declaration of our rights and liberties. The rights themselves thus defined by these several statutes . . . were formerly, either by inheritance or purchase, the rights of all mankind; but, in most other countries of the world being now more or less debased and destroyed, they at present may be said to remain, in a peculiar and emphatical manner, the rights of the people of England. And these may be reduced to three principal or primary articles; the right of personal security, the right of personal liberty and the right of private property. . . .

The law not only regards life and member, and protects every man in the enjoyment of them, but also furnishes him with every thing necessary for their support. . . .

The third absolute right, inherent in every Englishman, is that of property: which consists in the free use, enjoyment, and disposal of all his acquisitions, without any control or diminution, save only by the laws of the land. . . .

[I]n vain would these rights be declared, ascertained, and protected by the dead letter of the laws, if the constitution had provided no other method to secure their actual enjoyment. It has therefore established certain other auxiliary subordinate rights of the subject, which serve principally as barriers to protect and maintain inviolate the three great and primary rights, of personal security, personal liberty, and private property. These are,

1. The constitution powers, and privileges of parliament . . .

2. The limitations of the king’s prerogative, by bounds so certain and notorious, that it is impossible he should exceed them without the consent of the people. . . .

3. A third subordinate right of every Englishman is that of applying to the courts of justice for redress of injuries. . . .

4. If there should happen any uncommon injury, or infringement of the rights beforementioned, which the ordinary course of law is too defective to reach, there still remains a fourth subordinate right appertaining to every individual, namely, the right of petitioning the king, or either house of parliament, for the redress of grievances. . . .

5. The fifth and last auxiliary right of the subject, that I shall at present mention, is that of having arms for their defence suitable to their condition and degree, and such as are allowed by law. Which . . . is indeed a public allowance, under due restrictions, of the natural right of resistance and self-preservation, when the sanctions of society and laws are found insufficient to restrain the violence of oppression. . . .

[T]his review of our situation may fully justify the observation of a learned French author [Montesqieu], who indeed generally both thought and wrote in the spirit of genuine freedom; and who hath not scrupled to profess, even in the very bosom of his native country, that the English is the only nation in the world, where political or civil liberty is the direct end of it’s constitution.

Chapter the Second: Of the Parliament—And herein consists the true excellence of the English government, that all the parts of it form a mutual check upon each other. In the legislature, the people are a check upon the nobility, and the nobility a check upon the people; by the mutual privilege of rejecting what the other has resolved: while the king is a check upon both, which preserves the executive power from encroachments. And this very executive power is again checked, and kept within due bounds by the two houses, through the privilege they have of enquiring into, impeaching, and punishing the conduct (not indeed of the king, which would destroy his constitutional independence; but, which is more beneficial to the public) of his evil and pernicious counsellors. Thus every branch of our civil polity supports and is supported, regulates and is regulated, by the rest. . . . Like three different powers in mechanics, they jointly impel the machine of government in a direction different from what either, acting by themselves, would have done; but at the same time in a direction partaking of each, and formed out of all; a direction which constitutes the true line of the liberty and happiness of the community. . . .

It must be owned that Mr Locke, and other theoretical writers, have held that “there remains still inherent in the people a supreme power to remove or alter the legislative, when they find the legislative act contrary to the trust reposed in them: for when such trust is abused, it is thereby forfeited, and devolves to those who gave it.” But however just this conclusion may be in theory, we cannot adopt it, nor argue from it, under any dispensation of government at present existing. For this devolution of power, to the people at large, includes in it a dissolution of the whole form of government established by that people, reduces all the members to their original state of equality, and by annihilating the sovereign power repeals all positive laws whatsoever before enacted. No human laws will therefore suppose a case, which at once must destroy all law, and compel men to build afresh upon a new foundation; nor will they make provision for so desperate an event, as must render all legal provisions ineffectual. So long therefore as the English constitution lasts, we may venture to affirm, that the power of parliament is absolute and without control.

Chapter the Seventh: Of the King’s Prerogative—After what has been premised in this chapter, I shall not (I trust) be considered as an advocate of arbitrary power, when I lay it down as a principle, that in the exertion of lawful prerogative, the king is and out to be absolute; that is, so far absolute, that there is no legal authority that can either delay or resist him. . . . I say, in the ordinary course of law; for I do not now speak of those extraordinary recourses to first principles, which are necessary when the contracts of society are in danger of dissolution, and the law proves too weak a defence against the violence of fraud or oppression.

In this distinct and separate existence of the judicial power, in a peculiar body of men, nominated indeed, but not removeable at pleasure, by the crown, consists one main preservative of the public liberty; which cannot subsist long in any state, unless the administration of common justice be in some degree separated both from the legislative and also from the executive power.