Historic Document

The Souls of Black Folk (“Of Mr. Booker T. Washington and Others”) (1903)

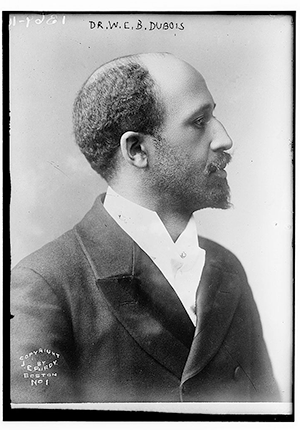

W.E.B. DuBois | 1903

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Summary

Born and raised in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, the Fisk, Harvard, and Berlin-educated historian, sociologist, economist, and man of letters, W.E.B. DuBois was the country’s pre-eminent black scholar and intellectual, and one the nation’s most prominent of any background. DuBois was simultaneously a political activist who mounted an aggressive, and often bitter, challenge, to the then-reigning “spokesman for the race,” Booker T. Washington, who had called upon blacks to accept Jim Crow segregation and disenfranchisement, and to prove themselves through hard-work, self-cultivation, and self-help, whereupon their achievements would ultimately be recognized, and full citizenship freely granted. DuBois, by contrast, called for immediate political and legal action and activism to win recognition of the constitutional rights and guarantees of full civic membership and inclusion promised by the Thirteenth (1865), Fourteenth (1868), and Fifteenth Amendments (1870), not least, in the last, of the purportedly guaranteed right to vote. DuBois’s vision of the political and legal strategy for immediate action, institutionalized in his role in founding, first, the Niagara Movement, and, then, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) (1909), underwrote the emerging civil rights vision, which charted a political and legal path for a movement committed to winning equal citizenship and full civic membership without regard to race, and to equal justice under law.

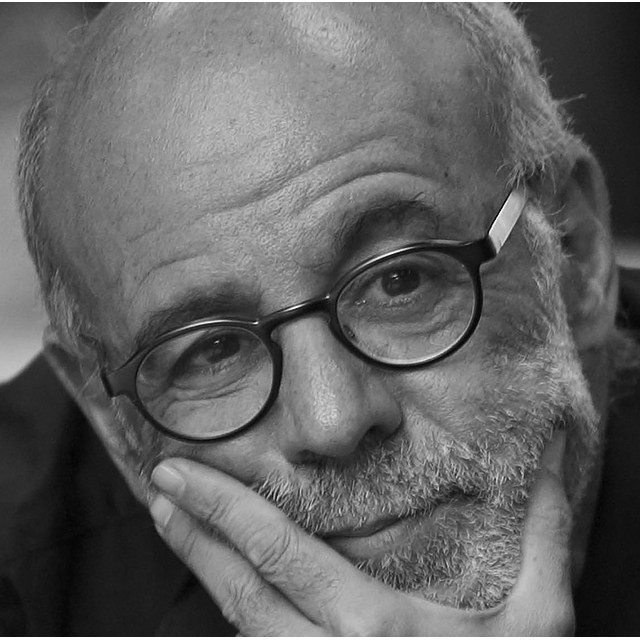

Selected by

William E. Forbath

Lloyd M. Bentsen Chair in Law, and Associate Dean for Research, The University of Texas at Austin School of Law

Ken I. Kersch

Professor of Political Science, at Boston College

Document Excerpt

Easily the most striking thing in the history of the American Negro since 1876 is the ascendency of Mr. Booker T. Washington…. Mr. Washington came, with a simple definite programme, at the psychological moment when the nation was a little ashamed of having bestowed so much sentiment on Negroes, and was concentrating its energies on Dollars…. His programme of industrial education, conciliation of the South, and submission and silence as to civil and political rights … startled and won the applause of the South, it interested and won the admiration of the North; and after a confused murmur of protest, it silenced if it did not convert the Negroes themselves….

“In all things purely social we can be as separate as the five fingers, and yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress.” This “Atlanta Compromise” is by all odds the most notable thing in Mr. Washington’s career….

Mr. Washington represents in Negro thought the old attitude of adjustment and submission; but adjustment at such a peculiar time as to make his programme unique. This is an age of unusual economic development, and Mr. Washington’s programme naturally takes an economic cast, becoming a gospel of Work and Money to such an extent as apparently almost completely to overshadow the higher aims of life. Moreover, this is an age when the more advanced races are coming in closer contact with the less developed races, and the race-feeling is therefore intensified; and Mr. Washington’s programme practically accepts the alleged inferiority of the Negro races…. Mr. Washington withdraws many of the high demands of Negroes as men and American citizens. In other periods of intensified prejudice all the Negro’s tendency to self-assertion has been called forth; at this period a policy of submission is advocated. In the history of nearly all other races and peoples the doctrine preached at such crises has been that manly self-respect is worth more than lands and houses, and that a people who voluntarily surrender such respect, or cease striving for it, are not worth civilizing….

Mr. Washington distinctly asks that black people give up, at least for the present, three things, -

First, political power,

Second, insistence on civil rights,

Third, higher education of Negro youth….

[Another] class of Negroes who cannot agree with Mr. Washington … feel in conscience bound to ask of this nation three things:

- The right to vote.

- Civic equality.

- The education of youth according to ability….

[O]n the whole the distinct impression left by Mr. Washington’s propaganda is, first, that the South is justified in its present attitude toward the Negro because of the Negro’s degredation; secondly, that the prime cause of the Negro’s failure to rise more quickly is his wrong education in the past; and thirdly, that his future depends primarily on his own efforts. Each of these propositions is a dangerous half-truth. The supplementary truths must never be lost sight of: first, slavery and race-prejudice are potent if not sufficient causes of the Negro’s position; second, industrial and common school training were necessarily slow in planting….; and, third, while it is a great truth to say that the Negro must strive and strive mightily to help himself, it is equally true that unless his striving be not simply seconded, but rather aroused and encouraged, by the initiative of the richer and wiser environing group, he cannot hope for great success…. His doctrine has tended to make the whites, North and South, shift the burdens of the Negro problem to the Negro’s shoulders and stand aside as critical and rather pessimistic spectators; when in fact the burden belongs to the nation, and the hands of none of us are clean if we bend not our energies to righting these great wrongs.