Historic Document

Speech Against the Eighteenth Amendment (1917)

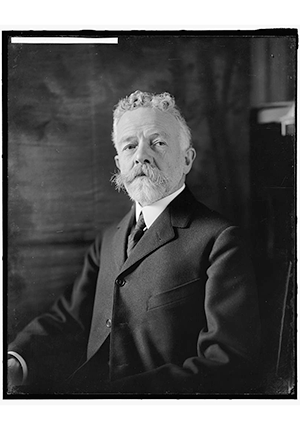

Henry Cabot Lodge | 1917

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, photograph by Harris & Ewing

Summary

The Harvard-educated lawyer, historian, political scientist, and Republican U.S. Representative and Senator from Massachusetts, Henry Cabot Lodge, a close friend and ally of Theodore Roosevelt, aggressively opposed the adoption of the Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution (1919), which imposed a direct federal ban on “the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors” within, or to and from, the United States, and gave concurrent enforcement powers to both Congress and the states. Lodge warned of the catastrophic effects of enacting a law – and here, part of the fundamental law of the Constitution – that not only lacked widespread popular support, but was likely to provoke widespread resistance and defiance. Lodge also objected that the Eighteenth Amendment scrambled the constitutional structure, which lodged the police powers to regulate matters of health, safety, and morals in the states, which had duly recognized that such regulations are best tailored to the diverse habits and morals of local communities, rather than being enforced uniformly nationally. Lodge proved prescient about Prohibition’s consequences, and the Eighteenth Amendment was repealed by the Twenty-First Amendment in 1933.

Selected by

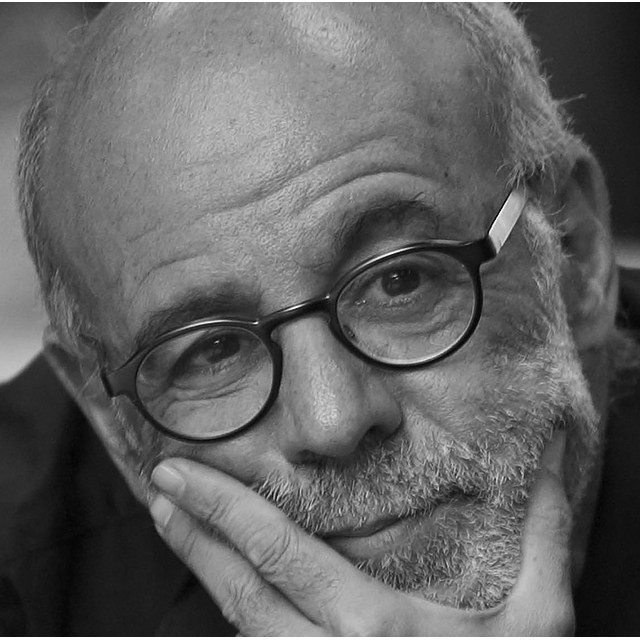

William E. Forbath

Lloyd M. Bentsen Chair in Law, and Associate Dean for Research, The University of Texas at Austin School of Law

Ken I. Kersch

Professor of Political Science, at Boston College

Document Excerpt

…I shall vote against the proposed constitutional amendment…. Personally, I firmly believe that every human being would be far better morally, mentally, and physically if he never touched alcohol…. But … I am not blind to the facts which surround the problem, and I can not vote for legislation which, in my opinion, would create a situation worse than that which now exists….

We are … dealing with what is perhaps the most deeply planted habit of human nature…. Without a prepared public sentiment among at least a majority of the people, such legislation as this is certain to fail. You will entirely destroy the control of the liquor traffic now exercised by regulations and licenses…. Multitudes of people will resent it as a gross and tyrannical interference with personal liberty…. The old habits [will be] maintained, but to the now undesirable character of the habits themselves there is now added that still more undesirable habit of lawbreaking….This combination of circumstances always tends to weaken the respect for law and to create a distrust of the powers of government in the minds of those who are called upon to obey and support it….

This proposed amendment in its local application seems to me even more objectionable than in its general features. The States will … cease to enforce prohibitory laws if they have them; they will be only too glad to get rid of the burden of the expense; and license laws will be impossible. The whole burden of enforcement will fall upon the General Government. … To enforce throughout the country …. [y]ou will have to search hundreds of houses…. Men who now drink quite harmlessly some beer or light wine will in a certain proportion turn to the consumption of distilled liquor…. You cannot hope to prevent the smuggling of liquor across our long frontiers or immense coasts…. Where large masses of the people would consider it even meritorious … to evade and break the law … I doubt if you could have an army large enough absolutely to enforce it….

[I]n a very short time we shall settle down to a condition like that presented by the amendments which attempted to confer full political rights upon the negroes of the United States [the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments], where the constitutional provision is entirely disregarded. They remain a dead letter in the Constitution….

[T]here are wide differences among the communities which make up the population of this country, and for that reason I believe that the sound foundation for the prohibition of alcohol should be set up in the local community and thence be extended to the counties, if necessary, and thence to the State. This question is better dealt with by the States than by the National Government…. The prohibition of liquor is essentially a police power…. I think we are taking a long step on a dangerous path when we take this police power from the States. The tendency now is to strip the States of one power after another that are conferred upon the National Government, forgetful that the strength and stability of our Government have depended upon the principle of local self-government embodied in the States. This attempt to hand over to the National Government the police power which properly belongs to the States will in its operation in other directions lead many people in the future to rue the day when they gave their support to a proposition so injurious to State Independence and to State power….