Historic Document

Speech Introducing the Fourteenth Amendment (1866)

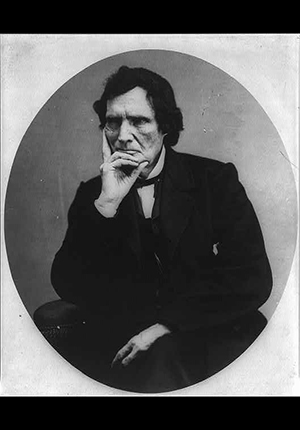

Thaddeus Stevens | 1866

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Summary

On May 8, 1866, Thaddeus Stevens delivered this speech introducing the Fourteenth Amendment in the U.S. House of Representatives. The leader of the Radical Republicans in the House, Stevens was a lawyer, politician, and staunch abolitionist. As a politician in Pennsylvania, he supported free public education and suffrage for African Americans. He also offered his home as a stop on the Underground Railroad. As a leader in Congress, Stevens fought to end slavery and promote civil rights and racial equality. He served on the Joint Committee on Reconstruction and chaired the powerful House Ways and Means Committee. In this speech, Stevens called on his colleagues to support the proposed Fourteenth Amendment—arguing that it would help to bring about legal equality for African Americans. However, he also urged colleagues to remember the crimes of the Confederacy.

Selected by

The National Constitution Center

Document Excerpt

The short time allowed by our resolution will suffice to introduce this debate. . . .

The [members of the Joint Committee on Reconstruction] are not ignorant of the fact that there has been some impatience at the delay in making this report . . . .

But I beg gentlemen to consider the magnitude of the task which was imposed upon the committee. They were expected to suggest a plan for rebuilding a shattered nation—a nation which though not dissevered was yet shaken and riven by the gigantic and persistent efforts of six million able and ardent men; of bitter rebels striving through four years of bloody war. It cannot be denied that this terrible struggle sprang from the vicious principles incorporated into the institutions of our country. Our fathers had been compelled to postpone the principles of their great Declaration, and wait for the full establishment till a more propitious time. That time ought to be present now. But the public mind has been educated in error for a century. How difficult in a day to unlearn it. In rebuilding, it is necessary to clear away the rotten and defective portions of the old foundations, and to sink deep and found the repaired edifice upon the firm foundation of eternal justice. If, perchance, the accumulated quicksands render it impossible to reach in every part so firm a basis, then it becomes our duty to drive deep and solid the substituted piles on which to build. It would not be wise to prevent the raising of the structure because some corner of it might be founded upon materials subject to the inevitable laws of mortal decay. It were better to shelter the household and trust to the advancing progress of a higher morality and a purer and more intelligent principle to underpin the defective corner.

I would not for a moment inculcate the idea of surrendering a principle vital to justice. But if full justice could not be obtained at once I would not refuse to do what is possible. The commander of an army who should find his enemy intrenched on impregnable heights would act unwisely if he insisted on marching his troops full in the face of a destructive fire merely to show his courage. Would it not be better to flank the works and march round and round and besiege, and thus secure the surrender of the enemy, though it might cost time? The former course would show valor and folly; the latter moral and physical courage, as well as prudence and wisdom. . . .

Let us now refer to the provisions of the proposed amendment.

The first section, prohibits the States from abridging the privileges and immunities of citizens of the United States, or unlawfully depriving them of life, liberty, or property, or of denying to any person within their jurisdiction the “equal” protection of the laws.

I can hardly believe that any person can be found who will not admit that every one of these provisions is just. They are all asserted, in some form or other, in our DECLARATION or organic law. But the Constitution limits only the action of Congress, and is not a limitation on the States. This amendment supplies that defect, and allows Congress to correct the unjust legislation of the States, so far that the law which, operates upon one man shall operate equally upon all. Whatever law punishes a white man for a crime shall punish the black man precisely in the same way and to the same degree. Whatever law protects the white man shall afford “equal” protection to the black man. Whatever means of redress is afforded to one shall be afforded to all. Whatever law allows the white man to testify in court shall allow the man of color to do the same. These are great advantages over their present codes. Now different degrees of punishment are inflicted, not on account of the magnitude of the crime, but according to the color of their skin. Now color disqualifies a man from testifying in courts, or being tried in the same way as white men. I need not enumerate these partial and oppressive laws. Unless the Constitution should restrain them, those States will all, I fear, keep up this discrimination and crush to death the hated freedmen. Some answer, “Your civil rights bill [the Civil Rights Act of 1866] secures the same things.” That is partly true, but a law is repealable by a majority. And I need hardly say that the first time that the South with their copperhead allies obtain the command of Congress it will be repealed. The veto of the President and their votes on the bill are conclusive evidence of that. And yet I am amazed and alarmed at the impatience of certain well-meaning Republicans at the exclusion of the rebel States until the Constitution shall be so amended as to restrain their despotic desires. This amendment once adopted cannot be annulled without two thirds of Congress. That they will hardly get. And yet certain of our distinguished friends propose to admit State after State before this becomes a part of the Constitution. What madness! Is their judgment misled by their kindness; or are they unconsciously drifting into the haven of power at the other end of the avenue? I do not suspect it, but others will.

The second section I consider the most important in the article. It fixes the basis of representation in Congress. If any State shall exclude any of her adult male citizens from the elective franchise, or abridge that right, she shall forfeit her right to representation in the same proportion. The effect of this provision will be either to compel the States to grant universal suffrage or so to shear them of their power as to keep them forever in a hopeless minority in the national Government, both legislative and executive. If they do not enfranchise the freedmen, it will give to the rebel States but thirty-seven Representatives. Thus short of their power, they would soon become restive. Southern pride would not long brook a hopeless minority. True it will take two, three, possibly five years before they conquer their prejudices sufficiently to allow their late slaves to become their equals at the polls. That short delay would not be injurious. In the meantime, the freedmen would become more enlightened, and more fit to discharge the high duties of their new condition. In that time, too, the loyal Congress could mature their laws and so amend the Constitution as to secure the rights of every human being and render disunion impossible. Heaven forbid that the southern states, or any one of them, should be represented by this floor until such monuments of freedom are built high and firm. Against our will they have been absent for four bloody years; against our will they must not come back until we are ready to receive them. Do not tell me that there are loyal representatives waiting for admission—until their States are loyal they can have no standing here. They would merely misrepresent their constituents. . . .

The third section may encounter more difference of opinion here. Among the people I believe it will be the most popular of all the provisions; it prohibits rebels from voting for members of Congress and electors of President until 1870. My only objection to it is that it is too lenient. I know that there is a morbid sensibility, sometimes called mercy, which affects a few of all classes, from the priest to the clown, which has more sympathy for the murderer on the gallows than for his victim. I hope I have a heart as capable of feeling for human woe as others. I have long since wished that capital punishment were abolished. But I never dreamed that all punishment could be dispensed with in human society. . . .