Historic Document

Annals (ca. 100-110)

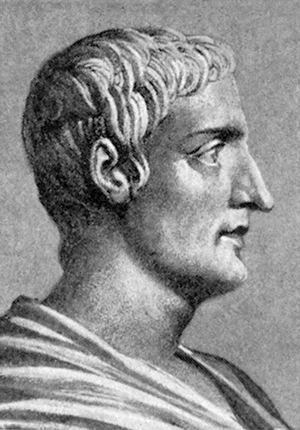

Tacitus | 100-110

Public domain

Summary

Publius Cornelius Tacitus (ca. 56-ca. 120) was the author of the Annals and the Histories, parts of which survive; and of the Agricola, the Dialogue on Oratory, and the Germania, which are intact. Tacitus turned to history, as had Sallust before him, after a political career. His, which began under the Flavians, took him all the way to the consulship, which he held as a suffect under the emperor Nerva. It was his hatred of tyranny, which he had witnessed in the time Domitian, that attracted the admiration of the radical Whigs in England and of the Founding generation in America. The opening lines of Tacitus’ Annals they found chilling.

Selected by

Paul Rahe

Professor of History and Charles O. Lee and Louise K. Lee Chair in the Western Heritage at Hillsdale College

Jeffrey Rosen

President and CEO, National Constitution Center

Colleen A. Sheehan

Professor of Politics at the Arizona State University School of Civic and Economic Thought and Leadership

Annals 1.1-15

KINGS were the original Magistrates of Rome. Lucius Brutus founded Liberty and the Consulship. Dictators were chosen only in pressing exigencies. Little more than two years prevailed the supreme power of the Decemvirate; and the consular jurisdiction of the military Tribunes, not very many. The domination of Cinna was but short; that of Sylla not long. The authority of Pompey and Crassus was quickly swallowed up in Cæsar; that of Lepidus and Anthony in Augustus. The Common-wealth, then long distressed and exhausted by civil dissensions, fell easily into his hands, and over her he assumed sovereign dominion, softened with the popular title of Prince of the Senate. But the several revolutions in the ancient free state of Rome, and all her happy or disastrous events, are already recorded by Writers of signal renown. Nor, even in the reign of Augustus, were there wanting Authors of distinction and genius to have composed his story, till by the prevailing spirit of flattery and abasement, they were checked. As to the succeeding Princes, Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius and Nero; the dread of their tyranny, whilst they yet reigned, falsified their history; and after their fall, the fresh detestation of their cruelties inflamed their Historians. Hence my own design of recounting briefly certain incidents in the reign of Augustus, chiefly towards his latter end, and of entering afterwards more fully into that of Tiberius and the other three, unbiassed by any resentment, or any affection, the influences of such personal passions being far from me.

When after the fall of Brutus and Cassius there remained none to fight for the Common-wealth, and her arms were no longer in her own hands; when Sextus Pompeius was utterly defeated in Sicily, Lepidus bereft of his command, Marc Anthony slain; and of all the chiefs of the late Dictator’s party, only Octavius his nephew was left; he put off the invidious name of Triumvir, and stiling himself Consul, pretended that the jurisdiction attached to the Tribuneship was his highest aim, as in it the protection of the populace was his only view. But when once he had secured the Soldiery by liberality and donations, gained the People by store of provisions, and charmed all by the blessings and sweetness of publick peace, he began by politick gradations to exalt himself, and with his own power to consolidate the authority of the Senate, jurisdiction of the Magistrate, and weight and force of the Laws; usurpations, in which he was thwarted by no man; all the most determined Republicans had fallen in battle, or by the late sanguinary Proscriptions; and for the surviving Nobility, they were covered with wealth, and distinguished with publick honours, according to the measure of their debasement, and promptness to bondage. Add, that all who in the loss of publick freedom had gained private fortunes, preferred a servile condition, safe and possessed, to the revival of ancient Liberty with personal peril. Neither were the Provinces averse to the present Revolution; since, under the Government of the People and Senate, they had lived in constant fear and mistrust, from the raging competition amongst our Grandces, as well as from the rapine and exactions of our Magistrates. In vain too had been their appeal to the Laws, which were utterly enfeebled and borne down by violence, by parties; nay, even by subornation and money.

Moreover, Augustus, to fortify his domination with collateral bulwarks, raised his sister’s son Claudius Marcellus, a perfect youth, to the dignity of Pontiff and that of Edile; preferred Marcus Agrippa to two successive Consulships, a man in truth meanly born, but an accomplished soldier, and the companion of his victories; and (Marcellus, the husband of Julia, soon after dying) chose him for his son-in-law. Even the sons of his wife, Tiberius Nero and Claudius Drusus, he dignified with high military titles and commands; though his house was yet supported by descendants of his own blood. For into the Julian family and name of the Cæsars he had already adopted Lucius and Caius, the sons of Agrippa; and though they were but children, neither of them seventeen years old, vehement had been his ambition to see them declared Princes of the Roman Youth, and even designed to the Consulship; while openly he was protesting against admitting these early honours. Presently upon the decease of Agrippa, were these his children snatched away, either by their own natural, but hasty fate, or by the deadly fraud of their step-mother Livia; Lucius on his journey to command the armies in Spain, Caius in his return from Armenia, ill of a wound. And as Drusus, one of her own sons, had been long since dead, Tiberius remained sole candidate for the succession. Upon this object centered all princely honours; he was by Augustus adopted for his son, assumed Collegue in the Empire, partner in the jurisdiction tribunitial, and presented under all these dignities to the several armies . . . . In profound tranquillity were affairs at Rome. To the Magistrates remained their wonted names; of the Romans the younger sort had been born since the battle of Actium, and even most of the old during the civil wars: How few were then living who had seen the ancient free state!

The frame and œconomy of Rome being thus totally overturned, amongst the Romans were no longer found any traces of their primitive spirit, or attachment to the virtuous institutions of antiquity. But as the equality of the whole was extinguished by the sovereignty of one, all men regarded the orders of the Prince as the only rule of conduct and obedience; nor felt they any anxiety, while Augustus yet retained vigour of life, and upheld the credit of his administration with publick peace, and the imperial fortune of his house. But when he became broken with age and infirmities; when his end was at hand, and thence a new source of hopes and views was presented, some few there were who began to reason idly about the blessings and recovery of Liberty; many dreaded a civil war, others longed for one; while far the greater part were uttering their several apprehensions of their future masters; “that naturally stern and savage was the temper of Agrippa, and by his publick contumely enraged into fury; and neither in age nor experience was he equal to the weight of Empire. Tiberius indeed had arrived at fulness of years, and was a distinguished captain, but possessed the inveterate pride entailed upon the Claudian race; and many indications of a cruel nature escaped him, in spite of all his arts to disguise it; besides that from his early infancy he was trained up in a reigning house, and even in his youth inured to an accumulation of power and honours, consulships and triumphs. Nor during the several years of his abode at Rhodes, where, under the plausible name of retirement, a real banishment was covered, did he exercise other occupation than that of meditating future vengeance, studying the arts of treachery, and practising secret and abominable sensualities. . . .

While the Public was engaged in these and the like debates, the illness of Augustus daily increased, and some strongly suspected the pestilent practices of his wife. . . . When she had taken all measures necessary in so great a conjuncture, in one and the same moment was published the departure of Augustus, and the accession of Tiberius.

Source:

The Works of Tacitus, vol. 1 - Gordon’s Discourses, Annals (Books 1-3)

https://oll.libertyfund.org/title/tacitus-the-works-of-tacitus-vol-1-gordons-discourses-annals-books-1-3