Historic Document

Remarks on Chinese Immigration (1882), 13 Cong. Rec. 1515–22

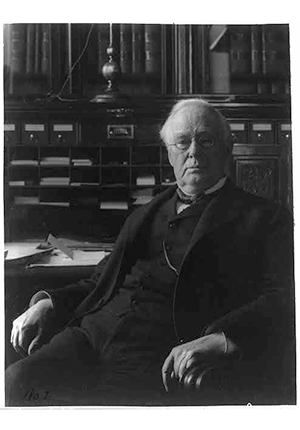

George Frisbie Hoar | 1882

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Frances Benjamin Johnston Photograph Collection

Summary

In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, which suspended the immigration of Chinese laborers (skilled or unskilled) for a period of 10 years. Advocates of exclusion were driven partly by the desire to protect white American workers from Chinese competition, but these arguments were far outweighed by those based on race. Introducing the bill into the Senate, Senator John F. Miller likened Chinese immigrants to “inhabitants of another planet.” Republican Senator George Frisbie Hoar was one of the few members of the Senate who spoke out against the Act. A lifelong opponent of slavery and a protégé of Charles Sumner, Hoar was among the founders of the Republican Party and had represented Massachusetts in Congress since 1869. A staunch defender of Black civil and political rights during Reconstruction and beyond, Hoar’s unswerving opposition to the Chinese Exclusion Act was of a piece with his anti-racism on behalf of African Americans, his broader anti-nativism, and his opposition to American imperialism. Hoar’s case against the Act responds both to nativists’ anti-Chinese racism and to the Gilded Age labor movement’s economic arguments about the baneful impact of cheap new immigrant labor upon the wages of white labor. The Chinese Exclusion Act ultimately passed Congress and was not repealed until 1943.

Selected by

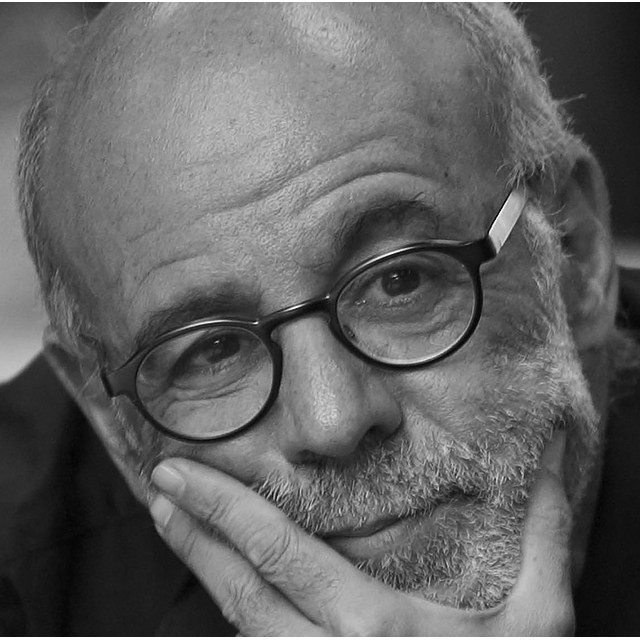

William E. Forbath

Lloyd M. Bentsen Chair in Law, and Associate Dean for Research, The University of Texas at Austin School of Law

Ken I. Kersch

Professor of Political Science, at Boston College

Document Excerpt

Nothing is more in conflict with the genius of American institutions than legal distinctions between individuals based upon race or upon occupation. The framers of our Constitution believed in the safety and wisdom of adherence to abstract principles. They meant that their laws should make no distinction between men except such as were required by personal conduct and character. The prejudices of race, the last of human delusions to be overcome, has been found until lately in our constitutions and statutes, and has left its hideous and ineradicable stains on our history in crimes committed by every generation. The negro, the Irishman, and the Indian have in turn been its victims here, as the Jew and the Greek and the Hindoo in Europe and Asia. But it is reserved for us at the present day, for the first time, to put into the public law of the world and into the national legislation of the foremost of republican nations a distinction inflicting upon a large class of men a degradation by reason of their race and by reason of their occupation. . . .

I will not consent to a denial by the United States of the right of every man who desires to improve his condition by honest labor—his labor being no man’s property but his own—to go anywhere on the face of the earth that he pleases. . . .

We go boasting of our democracy, and our superiority, and our strength. The flag bears the stars of hope to all nations. A hundred thousand Chinese land in California and everything is changed. God has not made of one blood all the nations any longer. The self-evident truth becomes a self-evident lie. The golden rule does not apply to the natives of the continent where it was first uttered. The United States surrender to China, the Republic to the despot, America to Asia, Jesus to Joss.

The advocates of this legislation appeal to a twofold motive for its support.

First. They invoke the old race prejudice which has so often played its hateful and bloody part in history.

Second. They say that the Chinese laborer works cheap and lives cheap, and so injures the American laborer with whom he competes.

The old race prejudice, ever fruitful of crime and of folly, has not been confined to monarchies or to the dark ages. Our own Republic and our own generation have yielded to this delusion, and have paid the terrible penalty. . . .

But it is urged, and this, in my judgment, is the greatest argument for the bill, that the introduction of the labor of the Chinese reduces the wages of the American laborer. “We are ruined by Chinese cheap labor” is a cry not limited to the class to whose representative the brilliant humorist of California first ascribed it. I am not in favor of lowering anywhere the wages of any American labor, skilled or unskilled. On the contrary, I believe the maintenance and the increase of the purchasing power of the wages of the American workingman should be the one principal object of our legislation. The share in the product of agriculture or manufacture which goes to labor should, and I believe will, steadily increase. For that, and for that only, exists our protective system. The acquisition of wealth, national or individual, is to be desired only for that. The statement of the accomplished Senator from California on this point meets my heartiest concurrence. I have no sympathy with any men, if such there be, who favor high protection and cheap labor.

But I believe that the Chinese, to whom the terms of the California Senator attribute skill enough to displace the American in every field requiring intellectual vigor, will learn very soon to insist on his full share of the product of his work. But whether that be true or not, the wealth he creates will make better and not worse the condition of every higher class of labor. There may be trouble or failure in adjusting new relations. But sooner or later every new class of industrious and productive laborers elevates the class it displaces. The dread of an injury to our labor from the Chinese rests on the same fallacy that opposed the introduction of labor-saving machinery, and which opposed the coming of the Irishman and the German and the Swede.