Historic Document

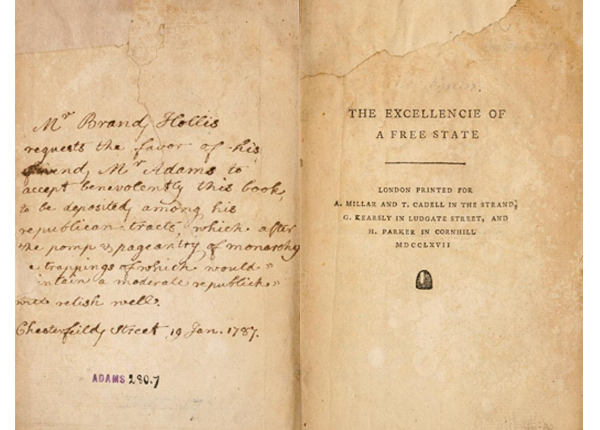

The Excellencie of a Free State (1656)

Marchamont Nedham | 1656

John Adams Library at the Boston Public Library

Summary

Marchamont Nedham (1620-78) was the world’s first celebrity journalist and author of The Case of the Commonwealth of England Stated (1650) and The Excellencie of a Free State (1656). Although he personally favored the parliamentary cause and was by no means averse to republicanism, his was a mercenary pen. In the 1640s and 1650s, he defended the Rump Parliament and then the Cromwellian Protectorate. After the Restoration, he wrote propaganda for Charles II and against the first earl of Shaftesbury. His pamphlet The Excellencie of a Free State foreshadowed the thinking of the radical Whigs of the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries and was much appreciated in America. Nedham’s dictum that “[t]he people are the best keepers of their own liberties” was a point of emphasis and some contention between John Adams and James Madison in the Founding period.

Selected by

Paul Rahe

Professor of History and Charles O. Lee and Louise K. Lee Chair in the Western Heritage at Hillsdale College

Jeffrey Rosen

President and CEO, National Constitution Center

Colleen A. Sheehan

Professor of Politics at the Arizona State University School of Civic and Economic Thought and Leadership

Document Excerpt

The EXCELLENCIE of a Free-State: or, The Right Constitution of a Commonwealth. Wherein All Objections are answered, and the best way to secure the Peoples LIBERTIES, discovered: with, Some Errors of Government, and Rules of Policie. Published by a Well-wisher to Posterity

The Romans having justly and nobly freed themselves from the Tyranny of Kings, and being in time brought to understand that the interest of Freedom consists in a due and orderly Succession of the Supreme Assemblies; they then made it their care, by all good ways and means, to fortifie the Commonwealth, and establish it in a free enjoyment of that Interest, as the onely bar to the return of Kings, and their main security against the subtil mining of Kingly humours and usurpations. . . .

Nor was it without reason, that this brave and active people were so studiously devoted to the preservation of their Freedom, when they had once attained it, considering how easie and excellent it is above all other Forms of Government, if it be kept within due bounds and order. It is an undeniable Rule, That the People (that is, such as shall be successively chosen to represent the People) are the best Keepers of their own Liberties; and that for these following Reasons. . . .

First, because they never think of usurping over other mens Rights, but minde which way to preserve their own. Whereas, the case is far otherwise among Kings and Grandees, as all Nations in the world have felt to some purpose: for they naturally move within the circle of domination, as in their proper Centre; and count it no less Security than Wisdom and Policy, to brave it over the People. . . .

A fourth Reason is, because a succession of supreme Powers doth not onely keep them from corruption, but it kills that grand Cankerworm of a Commonwealth, to wit, Faction: for, as Faction is an adhering to, and a promoting of an Interest, that is distinct from the true and declared Interest of State: so it is a matter of necessity, that those that drive it on, must have time to improve their slights and projects, in disguising their designs, drawing in Instruments and Parties, and in worming out of their opposites. The effecting of all this, requires some length of time: therefore the only prevention is a due succession and revolution of Authority in the Hands of the People. . . .

That this is most true, appears not onely by Reason, but by Example: if we observe the several turns of Faction in the Romane Government. What made their Kings so bold, as to incroach and tyrannize over the People, but the very same course that heightned our Kings heretofore in England, to wit, a continuation of Power in their own Persons and Families? Then, after the Romans became a Commonwealth, was it not for the same Reason, that the Senate fell into such heats and fits among themselves? . . . How came it to pass likewise, that Julius Caesar aspired, and in the end attained the Empire? and, that the People of Rome quite lost their Liberty, was it not by the same means? . . .

After the death of Caesar, it was probable enough, they might then have recovered their Liberty, but that they ran again into the same Error, as before: for by a continuation of Power in the hands of Octavius, Lepidus, and Antonie, the Commonwealth came to be rent and divided into three several Factions; two of which being worn out by each other, onely Octavius remained; who considering, that the Title of perpetual Dictator was the ruine of his Father Julius, continued the Government onely for a set-time, and procured it to be setled upon himself but for ten yeers. But what was the effect of this continuation of Power? Even this, That as the former protractings had been the occasions of Faction, so this produced a Tyranny . . . .

The Observation then arising from hence, is this, that the onely way for a people to preserve themselves in the enjoyment of their Freedom, and to avoid those fatal inconveniences of Faction and Tyranny, is, to maintain a due and orderly succession of Power and Persons. This was, and is, good Commonwealths Language; and without this Rule, it is impossible any Nation should long subsist in a State of Freedom. So that the Wisdom, the Piety, the Justice, and the self-denial of those Governours in Free-States, is worthy of all honour and admiration, who have, or shall at any time as willingly resign their Trusts, as ever they took them up; and have so far denied themselves, as to prefix Limits and Bounds to their own Authority. . . .

A sixth Reason, why a Free-State is much more excellent than a Government by Grandees or Kings; and, that the People are the best Keepers of their own Liberties, is, because, as the end of all Government is (or ought to be) the good and ease of the People, in a secure enjoyment of their Rights, without Pressure and Oppression: so questionless the People, who are most sensible of their own Burthens, being once put into a capacity and Freedom of Acting, are the most likely to provide Remedies for their own Relief; they onely know where the shooe wrings, what Grievances are most heavy, and what future Fences they stand in need of, to shelter them from the injurious Assaults of those Powers that are above them: and therefore it is but Reason, they should see that none be interested in the supreme Authority, but Persons of their own election, and such as must in a short time return again into the same condition with themselves, to reap the same Benefit or Burthen, by the Laws enacted, that befalls the rest of the People. Then the issue of such a Constitution must needs be this, That no Load shall be laid upon any, but what is common to all, and that always by common consent; not to serve the Lusts of any, but onely to supply the Necessities of their Country. . . .

A twelfth Reason is, because this Form is most sutable to the Nature and Reason of Mankinde: . . . for, as Cicero saith, Man is a noble Creature, born with Affections to rule, rather than obey; there being in every man a natural appetite or desire of Principality. And therefore the Reason why one man is content to submit to the Government of another, is, not because he conceives himself to have less right than another to govern; but either because he findes himself less able, or else because he judgeth it will be more convenient for himself, and that community whereof he is a Member, if he submits unto another’s Government. . . . From . . . expressions of that Oracle of Humane wisdom, these three Inferences do naturally arise: First, that by the light of Nature people are taught to be their own Carvers and Contrivers, in the framing of that Government under which they mean to live. Secondly, that none are to preside in Government, or sit at the Helm, but such as shall be judged fit, and chosen by the People. Thirdly, that the People are the onely proper Judges of the convenience or inconvenience of a Government when it is erected, and of the behaviour of Governours after they are chosen: which three Deductions appear to be no more, but an Explanation of this most excellent Maxime, That the Original and Fountain of all just Power and Government is in the People. . . .

A fourteenth Reason, (and though the last, yet not the least) to prove a Free-State or Government by the People, setled in a due and orderly succession of their supreme Assemblies, is much more excellent than any other Form, is, because in this Form, all Powers are accountable for misdemeanors in Government, in regard of the nimble Returns and Periods of the Peoples Election: by which means, he that ere-while was a Governour, being reduced to the condition of a Subject, lies open to the force of the Laws, and may with ease be brought to punishment for his offence; so that after the observation of such a course, others which succeed, will become the less daring to offend, or to abuse their Trust in Authority, to an oppression of the People. Such a course as this, cuts the very throat of all Tyranny . . . .

The Inference from the fore-going particulars, is easie, That since Freedom is to be preserved no other way in a Commonwealth, but by keeping Officers and Governours in an accountable state; and since it appears no standing Powers can never be called to an account without much difficulty, or involving a Nation in Blood or Misery. And since a revolution of Government in the Peoples hands, hath ever been the onely means to make Governours accountable, and prevent the inconveniences of Tyranny, Distraction, and Misery; therefore for this, and those other reasons fore-going, we may conclude, That a Free-State, or Government by the People, setled in a due and orderly succession of their supreme Assemblies, is far more excellent every way, than any other Form whatsoever.

Source: Marchamont Nedham, Excellencie of a Free-State [1656] , The Online Library of Liberty A Project Of Liberty Fund, Inc.

http://files.libertyfund.org/files/2449/Nedham_11600_EBk_v6.0.pdf