Historic Document

Thoughts on Government (1776)

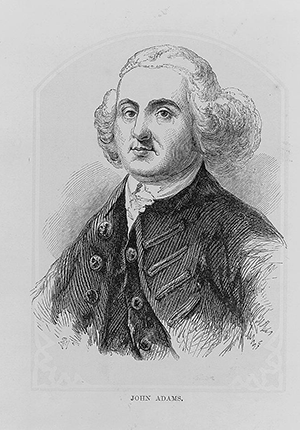

John Adams | 1776

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Summary

Early in 1776, John Adams dove into constitutional deliberations in the Massachusetts General Court. He authored the proclamation adopted in January 1776 and summoning citizens and civil officers to constitutional deliberations intended to realize the happiness of the people as the sole end of Government and founded inconsistent. Not long thereafter, he penned his Thoughts on Government as a full elaboration of the principles set forth in the proclamation of the General Court. Those principles were that “happiness is the end of government,” “consent the means,” and “sovereignty of the people” the foundation.

Selected by

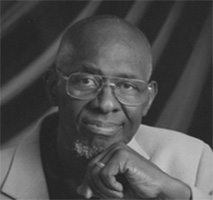

William B. Allen

Emeritus Dean of James Madison College and Emeritus Professor of Political Science at Michigan State University

Jonathan Gienapp

Associate Professor of History at Stanford University

Document Excerpt

[T]he divine science of politicks is the science of social happiness, and the blessings of society depend entirely on the constitutions of government, which are generally institutions that last for many generations, there can be no employment more agreeable to a benevolent mind, than a research after the best.

Pope flattered tyrants too much when he said

For forms of government let fools contest,

That which is best administered is best.

Nothing can be more fallacious than this: But poets read history to collect flowers not fruits — they attend to fanciful images, not the effects of social institutions. Nothing is more certain from the history of nations, and the nature of man, than that some forms of government are better fitted for being well administered than others.

We ought to consider what is the end of government, before we determine which is the best form. — Upon this point all speculative politicians will agree, that the happiness of society is the end of government, as all Divines and moral Philosophers will agree that the happiness of the individual is the end of man. From this principle it will follow, that the form of government, which communicates ease, comfort, security, or in one word happiness to the greatest number of persons, and in the greatest degree, is the best.

…

If there is a form of government then, whose principle and foundation is virtue, will not every sober man acknowledge it better calculated to promote the general happiness than any other form?

Honour is truly sacred, but holds a lower rank in the scale of moral excellence than virtue. —Indeed the former is but a part of the latter, and consequently has not equal pretensions to support a frame of government productive of human happiness.

The foundation of every government is some principle or passion in the minds of the people. — The noblest principles and most generous affections in our nature then, have the fairest chance to support the noblest and most generous models of government.

A MAN must be indifferent to the sneers of modern Englishmen, to mention in their company, the names of Sidney, Harrington, Locke, Milton, Nedham, Neville, Burnet, and Hoadley. — No small fortitude is necessary to confess that one has read them. The wretched condition of this country, however, for ten or fifteen years past, has frequently reminded me of their principles and reasonings. They will convince any candid mind, that there is no good government but what is Republican. That the only valuable part of the British Constitution is so; because the very definition of a Republic, is “an Empire of Laws, and not of Men.” That, as a Republic is the best of governments, so that particular arrangement of the powers of society, or in other words that form of government, which is best contrived to secure an impartial and exact execution of the laws, is the best of Republics.

…

As good government, is an empire of laws, how shall your laws be made? In a large society, inhabiting an extensive country, it is impossible that the whole should assemble, to make laws: The first necessary step then, is, to depute power from the many, to a few of the most wise and good. — But by what rules shall you choose your Representatives? Agree upon the number and qualification of persons, who shall have the benefit of choosing, or annex this privilege to the inhabitants of a certain extent of ground.

The principal difficulty lies, and the greatest care should be employed in constituting this Representative Assembly. It should be in miniature, an exact portrait of the people at large. It should think, feel, reason, and act like them. That it may be the interest of this Assembly to do strict justice at all times, it should be an equal representation, or in other words equal interest among the people should have equal interest in it. — Great care should be taken to effect this, and to prevent unfair, partial, and corrupt elections.

…

A REPRESENTATION of the people in one Assembly obtained, a question arises whether all the powers of government, legislative, executive, and judicial, shall be left in this body? I think a people cannot be long free, nor ever happy, whose government is one Assembly. My reasons for this opinion are as follow:

1. A SINGLE Assembly is liable to all the vices, follies and frailties of an individual. — Subject to fits of humour, starts of passion, flights of enthusiasm, partialities of prejudice, and consequently productive of hasty results and absurd judgments. …

Most of the foregoing reasons apply equally to prove that the legislative power ought to be more complex — to which we may add, that if the legislative power is wholly in one Assembly, and the executive in another, or in a single person, these two powers will oppose and enervate upon each other, until the contest shall end in war, and the whole power, legislative and executive, be usurped by the strongest.

…

To avoid these dangers let a distant Assembly be constituted, as a mediator between the two extreme branches of the legislature, that which represents the people and that which is vested with the executive power.

Let the Representative Assembly then elect by ballot, from among themselves or their constituents, or both, a distinct Assembly, which…we will call a Council. It…should have a free and independent exercise of its judgment, and consequently a negative voice in the legislature.

These two bodies thus constituted and made integral parts of the legislature, let them unite, and by joint ballot choose a Governor...

…

These and all other elections, especially of Representatives and Councillors, should be annual, there not being in the whole circle of the sciences, a maxim more infallible than this, “Where annual elections end, there slavery begins.”

…

A ROTATION of all offices, as well as of Representatives and Councillors, has many advocates, and is contested for with many plausible arguments.

…

The dignity and stability of government in all its branches, the morals of the people and every blessing of society, depends so much upon an upright and skillful administration of justice, that the judicial power ought to be distinct from the legislative and executive, and independent upon both, that so it may be a check upon both, as both should be checks upon that. The Judges therefore should always be men of learning and experience in the laws, of exemplary morals, great patience, calmness, coolness and attention….To the ends they should hold estates for life in their offices, or in other words their commissions should be during good behaviour.

…

Laws for the liberal education of youth, especially of the lower class of people, are so extremely wise and useful, that to a humane and generous mind, no expence for this purpose would be thought extravagant.

The very mention of sumptuary laws will excite a smile. Whether our countrymen have wisdom and virtue enough to submit to them I know not. But the happiness of the people might be greatly promoted by them.

…

A CONSTITUTION, founded on these principles, introduces knowledge among the People, and inspires them with a conscious dignity, becoming Freemen. A general emulation takes place, which causes good humour, sociability, good manners, and good morals to be general. That elevation of sentiment, inspired by such a government, makes the common people brave and enterprising. That ambition which is inspired by it makes him sober, industrious and frugal.

…

You and I, my dear Friend, have been sent into life at a time when the greatest lawgivers of antiquity would have wished to have lived. – How few of the human race have ever enjoyed an opportunity of making an election of government more than of air, soil, or climate, for themselves or their children. — When! Before the present epocha, had three millions of people full power and a fair opportunity to form and establish the wisest and happiest government that human wisdom can contrive?...