Historic Document

Political Recollections, 1840-1872 (1884)

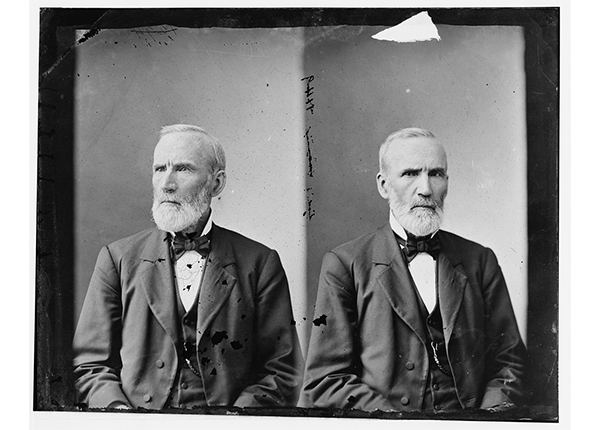

George Washington Julian | 1840-1872

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Brady-Handy photograph collection

Summary

George Julian was an abolitionist lawyer, serving first in the Indiana legislature, then in the U.S. House of Representatives as a Free Soiler (1849-51) and then a Republican (1861-71). He identified with the Radical Republican faction, and was prominent in pressing for emancipation, the recruitment of black soldiers, the confiscation of rebel property, and the Homestead Act. Although critical of Lincoln for not moving more vigorously against slavery, Julian nevertheless supported Lincoln’s reelection in 1864, and in his memoirs, left a vivid testimony to the final vote in the House of Representatives on January 30, 1865, for the Thirteenth Amendment, which abolished slavery. Lincoln described this amendment as “a king’s cure for all the evils” of slavery.

Selected by

Allen C. Guelzo

Director, Initiative on Politics and Statesmanship, James Madison Program in American Ideals and Institutions, Princeton University

Darrell A.H. Miller

Melvin G. Shimm Professor of Law at Duke University School of Law

Document Excerpt

A Union with slavery spared and reinstated would not be worth the cost of saving it. To argue that we fighting for a political abstraction called the Union, and not for the destruction of slavery, was to affront common sense, since nothing but slavery had brought the Union into peril, and nothing could make sure the fruits of the war but the removal of its cause. It was to delude ourselves with mere phrases, and conduct the war on false pretenses.

…Congress had abolished slavery in the District of Columbia, and prohibited it in all the Territories. It had repealed the Fugitive Slave law, and declared free all negro soldiers in the Union armies and their families; and the President had played his grand part in the Proclamation of Emancipation. But the question now to be decided completely overshadowed all others. The debate on the subject had been protracted and very spirited…. The time for the momentous vote had now come, and no language could describe the solemnity and impressiveness of the spectacle pending the roll-call. The success of the measure had been considered very doubtful, and depended upon certain negotiations, the result of which was not fully assured, and the particulars of which never reached the public. The anxiety and suspense during the balloting produced a deathly stillness, but when it became certainly known that the measure had prevailed the cheering in the densely-packed hall and galleries surpassed all precedent and beggared all description. Members joined in the general shouting, which was kept up for several minutes, many embracing each other, and others completely surrendering themselves to their tears of joy.

It seemed to me I had been born into a new life, and that the world was overflowing with beauty and joy, while I was inexpressibly thankful for the privilege of recording my name on so glorious a page of the nation’s history, and in testimony of an event so long only dreamed of as possible in the distant future. The champions of negro emancipation had merely hoped to speed their grand cause a little by their faithful labors, and hand over to coming generations the glory of crowning it with success; but they now saw it triumphant, and they had abundant and unbounded cause to rejoice.

…A few days after the ratification of this Amendment, on the motion of Mr. [Charles] Sumner, Dr. [John S.] Rock, a colored lawyer of Boston, was admitted to practice in the Supreme Court of the United States, which had pronounced the Dred Scott decision only a few years before; and this was followed a few days later by a sermon in the hall of the House by Rev. Mr. [Henry Highland] Garnett, being the first ever preached in the Capitol by a colored man. Evidently, the negro was coming to the front.