Historic Document

Debate in Union Hall, Cambridge University (1965)

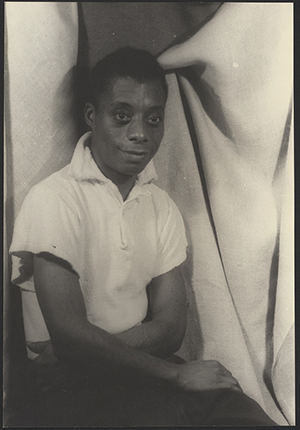

James Baldwin and William F. Buckley | 1965

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Carl Van Vechten Collection

Summary

The 1965 debate between noted author and civil rights activist James Baldwin and William F. Buckley, Jr., writer and “Father of the Modern Conservative Movement,” took place at a most challenging juncture in American social history. The 1965 Voting Rights Act, which became law in August of 1965, about six months after this debate, received massive public attention. Those in favor maintained that it was long overdue for the 15th Amendment (1870) to be fully and consistently enforced, and this was the position taken by Baldwin. Buckley held that it was a state matter.

Selected by

Christopher Brooks

Professor of History, East Stroudsburg University

Kenneth Mack

Lawrence D. Biele Professor of Law, Harvard Law School

Document Excerpt

James Baldwin:

It is only since the Second World War that there’s been a counter-image in the world. And that image did not come about through any legislation or part of any American government, but through the fact that Africa was suddenly on the stage of the world, and Africans had to be dealt with in a way they’d never been dealt with before. This gave an American Negro for the first time a sense of himself beyond the savage or a clown. It has created and will create a great many conundrums. One of the great things that the white world does not know, but I think I do know, is that Black people are just like everybody else. One has used the myth of Negro and the myth of color to pretend and to assume that you were dealing with, essentially, with something exotic, bizarre, and practically, according to human laws, unknown. Alas, it is not true. We’re also mercenaries, dictators, murderers, liars. We are human too.

What is crucial here is that unless we can manage to accept, establish some kind of dialog between those people whom I pretend have paid for the American dream and those other people who have not achieved it, we will be in terrible trouble. I want to say, at the end, the last, is that is what concerns me most. We are sitting in this room, and we are all, at least I’d like to think we are, relatively civilized, and we can talk to each other at least on certain levels so that we could walk out of here assuming that the measure of our enlightenment, or at least, our politeness, has some effect on the world. It may not.

. . .

William F. Buckley, Jr.:

[Interjection from an American undergraduate: “Mr. Buckley, one thing you can do is to let them [African Americans] vote in Mississippi!”]

[Buckley responds]

I agree. Except, lest I appear too ingratiating, I think actually what is wrong in Mississippi is not that not enough Negros have the vote but that too many white people are voting.

What we need is a considerable amount of frankness that acknowledges there are two sets of difficulties. We must recognize the difficulty that brown people, white people, black people, have all over the world to protect their own vested interests. They suffer from a kind of racial narcissism which tends always to convert every contingency in such a way as to maximize their own power. We must acknowledge that problem, but we must also reach through to the Negro people and tell them that their best chances are in mobile society and the most mobile society in the world is the United States.