Historic Document

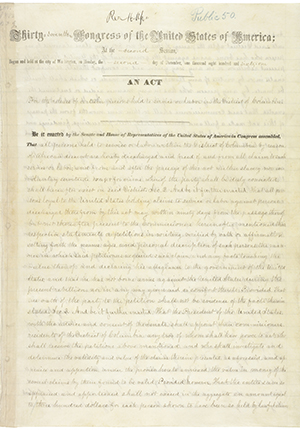

Contemporary Documents on the District Emancipation Bill (1862)

Various | 1862

National Archives

Summary

The District of Columbia emancipation bill passed the U.S. Senate on April 3rd and the House of Representatives on April 11th, and was signed into law by President Lincoln on April 16, 1862. Even before Lincoln had put his signature to the bill, it was already the center of both jubilation and controversy. As the first legal step taken by Congress toward emancipation, it was widely interpreted as a presage of further steps to come. Henry Ward Beecher, the famed abolitionist pastor of the Plymouth Church in Brooklyn, hailed the bill in his Sunday sermon on April 13th as a landmark in the progress toward abolition. The New York Times, edited by the moderate Republican Henry J. Raymond, adopted a middle way, applauding mildly the end of slavery in the District while not approving of the bill itself. The Democratic Indiana State Sentinel, published in both daily and weekly editions by John R. Elder and John Harkness, attacked the emancipation bill as a deplorable example of what Republican “revolutionists” intended to force on the country.

Selected by

Allen C. Guelzo

Director, Initiative on Politics and Statesmanship, James Madison Program in American Ideals and Institutions, Princeton University

Darrell A.H. Miller

Melvin G. Shimm Professor of Law at Duke University School of Law

Document Excerpt

Henry Ward Beecher, “The Success of American Democracy,” April 13, 1862:

I think there is a widening conviction, that slavery and its laws, and liberty and its institutions, cannot exist under one government. And I think that, if it were not for the impediment of supposed constitutional restrictions there would be an almost universal disposition to sweep, as with a deluge, this gigantic evil out of our land. The feeling of the people in this matter is unmistakable. The recommendation of the President of these United States, which has been corroborated by the resolution of Congress, is one of the most memorable events of our history. The fact that a policy of emancipation has been recommended by the Chief Magistrate, and indorsed by Congress, cannot be overestimated in importance. …Last Friday — a day not henceforth to be counted inauspicious — was passed the memorable bill giving liberty to the slave in the District of Columbia. One might almost say, if the President had signed it, “Lord, now let thy servant depart in peace, according to thy word; for mine eyes have seen thy salvation.” It is worth living for a lifetime to see the capital of our government redeemed from the stigma and shame of being a slave mart. I cannot doubt that the President of the United States will sign that bill. …It would have been better if it had been signed the moment that it was received; but we have found out by experience that though Abraham Lincoln is sure, he is slow; and that though he is slow, he is sure!

New York Times, April 17, 1862:

The act of the President, in signing a bill to put an end to Slavery in the District of Columbia, places the Government of this country in its proper position, in reference to the subject of human bondage. It is a declaration that its sympathies and its action, as far as they can be constitutionally exerted, are henceforth to be in favor of freedom, as better in a moral point of view, and more economic in a material one, than Slavery. Such is the genius of the age, as well as Christianity. This act of Government is but the record of a progress in this country in liberal ideas, common to the whole civilized world. …We cannot avoid the effect of the moral if we would, while the action of the slaveholding section has fully warranted Government in affirming a judgment irresistibly sustained by results, and at the same time by the general sense of mankind. Henceforth it will stand as the representative of freedom and progress….

In all radical changes the only way to proceed safely is to proceed slowly, in which case experience will supply guidance to our conduct as we move along. But, while objecting to the mode, we emphatically approve the principles which lay at the foundation of this new declaration of human rights, which cannot fail in the end, by eliminating, through the working of natural laws, and by peaceful modes, the only real cause of discord, to render us a perfectly harmonious and united people.

Indiana State Sentinel, April 21, 1862:

No one…can be so blind as not to see that a powerful effort is being made to change the character of the contest, or the objects to be accomplished in its prosecution. With a large portion of the Republicans the spirit of conquest animates them and the subjugation of the rebel States is not only a cherished but avowed purpose. The proposition to overthrow those States and hold and govern them as conquered provinces is boldly announced and advocated. The initiatory step for interfering with the institutions of the States has been taken. The abolition of slavery in the District of Columbia is hailed by the Revolutionists as the beginning of the end – the inauguration of the policy of forcible emancipation wherever slavery exists…and a leading Republican paper has put the prediction on record that in less than twelve months the President will issue an edict of general emancipation as a “military necessity.” …If that event should occur…can any other conclusion be formed than that slavery must terminate by the voluntary action of the States where it exists, or else by the direct, forcible interposition of the General Government?

…We are rapidly drifting toward a revolution of the Government – in fact, we may better say that we are in the midst of a revolution. …The revolutionists have the direction of the Government, and will use the power in their hands for the accomplishment of their emancipation schemes, unless the people promptly interpose and crush them, and restrict the prosecution of the war to the objects to which the country is solemnly pledged.

Sources: Patriotic Addresses in America and England from 1850 to 1885, on Slavery (New York: Fords, Howard & Hulbert, 1891), 354;

Henry Ward Beecher, The Success of American Democracy, April 13, 1862.