Historic Document

Report on the Condition of the South (1865)

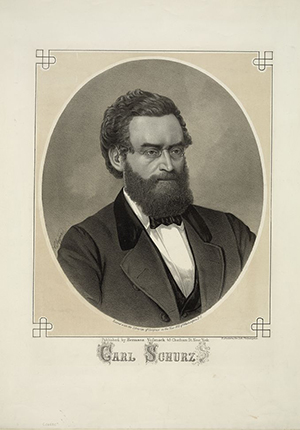

Carl Schurz | December 18,1865

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Summary

Carl Schurz was a German immigrant, Union general, journalist, and eventually, United States Senator from Missouri. Shortly after Schurz resigned his military commission, President Andrew Johnson assigned him to investigate the conditions of the South and to draft a report. Schurz’s report warned of widespread abuse of Freedmen after emancipation and predicted dire consequences to African Americans, Unionists, and their allies if Southerners were able to reconstitute local militias and other domestic security institutions. Although his report was ignored by Johnson, Schurz’s observations proved to be prescient, leading to more protective enactments by Congress under its power to enforce the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments.

Selected by

Allen C. Guelzo

Director, Initiative on Politics and Statesmanship, James Madison Program in American Ideals and Institutions, Princeton University

Darrell A.H. Miller

Melvin G. Shimm Professor of Law at Duke University School of Law

Document Excerpt

Washington, D.C., December 18, 1865.

Report of Carl Schurz on the States of South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana.

A belief, conviction, or prejudice, or whatever you may call it, so widely spread and apparently so deeply rooted as this, that the negro will not work without physical compulsion, is certainly calculated to have a very serious influence upon the conduct of the people entertaining it. It naturally produced a desire to preserve slavery in its original form as much and as long as possible…. Efforts were, indeed, made to hold the negro in his old state of subjection, especially in such localities where our military forces had not yet penetrated, or where the country was not garrisoned in detail. Here and there planters succeeded for a limited period to keep their former slaves in ignorance, or at least doubt, about their new rights; but the main agency employed for that purpose was force and intimidation. In many instances negroes who walked away from the plantations, or were found upon the roads, were shot or otherwise severely punished, which was calculated to produce the impression among those remaining with their masters that an attempt to escape from slavery would result in certain destruction.

…Here I will insert some remarks on the general treatment of the blacks as a class, from the whites as a class. It is not on the plantations and at the hands of the planters themselves that the negroes have to suffer the greatest hardships. Not only the former slaveholders, but the non-slaveholding whites, who, even previous to the war, seemed to be more ardent in their pro-slavery feelings than the planters themselves, are possessed by a singularly bitter and vindictive feeling against the colored race since the negro has ceased to be property. The pecuniary value which the individual negro formerly represented having disappeared, the maiming and killing of colored men seems to be looked upon by many as one of those venial offences which must be forgiven to the outraged feelings of a wronged and robbed people.

…These statements are naturally not intended to apply to all the individuals composing the southern people…. There are certainly many people there who entertain the best wishes for the welfare of the negro race, and who not only never participated in any acts of violence, but who heartily disapprove them…. But however large or small a number of people may be guilty of complicity in such acts of persecution, those who are opposed to them have certainly not shown themselves strong enough to restrain those who perpetrate or favor them. …It must not be forgotten that in a community a majority of whose members is peaceably disposed, but not willing or not able to enforce peace and order, a comparatively small number of bold and lawless men can determine the character of the whole. The rebellion itself, in some of the southern States, furnished a striking illustration of this truth.

…Clearer and more significant was the ord[i]nance passed by the police board of the town of Opelousas, Louisiana…. The negro is not only not permitted to be idle, but he is positively prohibited from working or carrying on a business for himself; he is compelled to be in the “regular service” of a white man, and if he has no employer he is compelled to find one. It requires only a simple understanding among the employers, and the negro is just as much bound to his employer “for better and for worse” as he was when slavery existed in the old form. If he should attempt to leave his employer on account of non-payment of wages or bad treatment he is compelled to find another one; and if no other will take him he will be compelled to return to him from whom he wanted to escape. The employers, under such circumstances, are naturally at liberty to arrange the matter of compensation according to their tastes, for the negro will be compelled to be in the regular service of an employer, whether he receives wages or not…. The sections providing for the “summary” enforcement of the penalties and placing their infliction into the hands of the “chief of patrol”—which, by the way, throws some light upon the objects for which the militia is to be reorganized—place the freedmen under a sort of permanent martial law, while the provision investing every white man with the power and authority of a police officer as against every black man subjects them to the control even of those individuals who in other communities are thought hardly fit to control themselves. On the whole, this piece of legislation is a striking embodiment of the idea that although the former owner has lost his individual right of property in the former slave, “the blacks at large belong to the whites at large.”