Historic Document

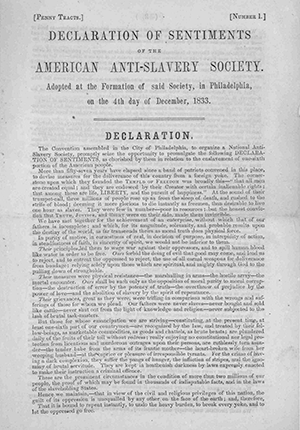

American Anti-Slavery Society Declaration of Sentiments (1833)

American Anti-Slavery Society | 1833

Library of Congress, Printed Ephemera Collection

Summary

Even before the American Revolution, anti-slavery societies began to emerge in the Northern states (Pennsylvania’s Abolition Society was established in 1775). In the early 1800s, the Protestant religious movement known as the Second Great Awakening added religious zeal to abolitionist advocacy and helped fuel the rise of numerous anti-slavery organizations. The most radical abolitionists, such as William Lloyd Garrison, denounced the U.S. Constitution as “an agreement with Hell” for allowing the existence of chattel slavery in the Southern states. Other anti-slavery societies accepted the Constitution’s federalist compromise with state-sanctioned slavery but passionately insisted that foundational texts such as the Declaration of Independence and the Fifth Amendment’s Due Process Clause were incompatible with slavery and obligated the national government to prohibit slavery wherever federal law controlled, particularly in the territories and in the District of Columbia. These societies had no interest in maintaining the status quo: they committed their members to preaching, speaking, and writing about the evils of slavery throughout the United States. The rise of abolitionist agitation soon triggered a response by Southern states who attempted to silence what they viewed as dangerous and inflammatory rhetoric.

Selected by

Laura F. Edwards

Class of 1921 Bicentennial Professor in the History of American Law and Liberty, and Professor of History at Princeton University

Kurt Lash

E. Claiborne Robins Distinguished Professor of Law at the University of Richmond

Document Excerpt

More than fifty-seven years have elapsed, since a band of patriots convened in this place, to devise measures for the deliverance of this country from a foreign yoke. The cornerstone upon which they founded the Temple of Freedom was broadly this—“that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, LIBERTY, and the pursuit of happiness.” . . .

Our fathers were never slaves—never bought and sold like cattle—never shut out from the light of knowledge and religion—never subjected to the lash of brutal taskmasters. But those, for whose emancipation we are striving— constituting at the present time at least one-sixth part of our countrymen—are recognized by law, and treated by their fellow-beings, as marketable commodities, as goods and chattels, as brute beasts; are plundered daily of the fruits of their toil without redress; really enjoy no constitutional nor legal protection from licentious and murderous outrages upon their persons; . . .

[N]o man has a right to enslave or imbrute his brother—to hold or acknowledge him, for one moment, as a piece of merchandise—to keep back his hire by fraud—or to brutalize his mind, by denying him the means of intellectual, social and moral improvement. The right to enjoy liberty is inalienable. To invade it is to usurp the prerogative of Jehovah. Every man has a right to his own body—to the products of his own labor—to the protection of law—and to the common advantages of society. It is piracy to buy or steal a native African, and subject him to servitude. Surely, the sin is as great to enslave an American as an African. . . .

We fully and unanimously recognise the sovereignty of each State, to legislate exclusively on the subject of the slavery which is tolerated within its limits; we concede that Congress, under the present national compact, has no right to interfere with any of the slave States, in relation to this momentous subject: But we maintain that Congress has a right, and is solemnly bound, to suppress the domestic slave trade between the several States, and to abolish slavery in those portions of our territory which the Constitution has placed under its exclusive jurisdiction. . . .

We shall organize Anti-Slavery Societies, if possible, in every city, town and village in our land. We shall send forth agents to lift up the voice of remonstrance, of warning, of entreaty, and of rebuke. We shall circulate, unsparingly and extensively, anti-slavery tracts and periodicals. We shall enlist the pulpit and the press in the cause of the suffering and the dumb. We shalt aim at a purification of the churches from all participation in the guilt of slavery