Historic Document

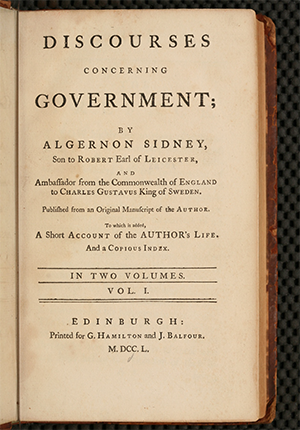

Discourses concerning Government (1698)

Algernon Sidney | 1698

John Adams Library at the Boston Public Library

Summary

Algernon Sidney (1623-83) was the author of Discourses concerning Government (1698) and the recently discovered Court Maxims (1996). Although born the son of the second earl of Leicester and, on his mother’s side, the grandson of the ninth earl of Northumberland, Sidney was a republican firebrand. He fought in the English Civil War on the side of Parliament. He served in the Long Parliament and was a member of the Rump; he denounced Oliver Cromwell as a tyrant; and, during the Restoration he conspired against Charles II, was executed, and entered the pantheon of republican martyrs. Written under the influence of Machiavelli and, like Locke’s Two Treatises of Government, in opposition to Sir Robert Filmer’s Patriarcha, Sidney’s Discourses concerning Government (which was deployed at Sidney’s trial and finally published well after his death) was a favorite of the radical Whigs and their American admirers. In particular, Sydney’s opposition to divine right of kings and articulation of popular sovereignty, consent of the governed, limited government, and the right of revolution resonated with the Founding generation.

Selected by

Paul Rahe

Professor of History and Charles O. Lee and Louise K. Lee Chair in the Western Heritage at Hillsdale College

Jeffrey Rosen

President and CEO, National Constitution Center

Colleen A. Sheehan

Professor of Politics at the Arizona State University School of Civic and Economic Thought and Leadership

Document Excerpt

Chapter 1:

Section 5—[T]here is more than ordinary extravagance in [Filmer’s] assertion, that the greatest liberty in the world is for a people to live under a monarch, when his whole book is to prove, that this monarch hath his right from God and nature, is endowed with an unlimited power of doing what he pleaseth, and can be restrained by no law. If it be liberty to live under such a government, I desire to know what is slavery. ...

Section 10—It were a folly hereupon to say, that the liberty for which we contend, is of no use to us, since we cannot endure the solitude, barbarity, weakness, want, misery and dangers that accompany it whilst we live alone, nor can enter into a society without resigning it; for the choice of that society, and the liberty of framing it according to our own wills, for our own good, is all we seek. This remains to us whilst we form governments, that we ourselves are judges how far ’tis good for us to recede from our natural liberty; which is of so great importance, that from thence only we can know whether we are freemen or slaves; and the difference between the best government and the worst, doth wholly depend upon a right or wrong exercise of that power. If men are naturally free, such as have wisdom and understanding will always frame good governments: But if they are born under the necessity of perpetual slavery, no wisdom can be of use to them; but all must forever depend on the will of their lords, how cruel, mad, proud or wicked soever they be.

Section 11—’Tis hard to comprehend how one man can come to be master of many, equal to himself in right, unless it be by consent or by force. If by consent, we are at an end of our controversies: Governments, and the magistrates that execute them, are created by man. They who give a being to them, cannot but have a right of regulating, limiting and directing them as best pleaseth themselves; and all our author’s assertions concerning the absolute power of one man, fall to the ground: If by force, we are to examine how it can be possible or justifiable. This subduing by force we call conquest; but as he that forceth must be stronger than those that are forced, to talk of one man who in strength exceeds many millions of men, is to go beyond the extravagance of fables and romances.

Chapter 2:

Section 1—The weakness in which we are born, renders us unable to attain this good of ourselves: we want help in all things, especially in the greatest. The fierce barbarity of a loose multitude, bound by no law, and regulated by no discipline, is wholly repugnant to it: Whilst every man fears his neighbour, and has no other defence than his own strength, he must live in that perpetual anxiety which is equally contrary to that happiness, and that sedate temper of mind which is required for the search of it. The first step towards the cure of this pestilent evil, is for many to join in one body, that everyone may be protected by the united force of all; and the various talents that men possess, may by good discipline be rendered useful to the whole; as the meanest piece of wood or stone being placed by a wise architect, conduces to the beauty of the most glorious building. But every man bearing in his own breast affections, passions, and vices that are repugnant to this end, and no man owing any submission to his neighbour; none will subject the correction or restriction of themselves to another, unless he also submit to the same rule. ...

Section 11—Machiavelli discoursing of these matters, finds virtue to be so essentially necessary to the establishment and preservation of liberty, that he thinks it impossible for a corrupted people to set up a good government, or for a tyranny to be introduced if they be virtuous; and makes this conclusion, That where the matter (that is, the body of the people) is not corrupted, tumults and disorders do no hurt; and where it is corrupted, good laws do no good: Which being confirmed by reason and experience, I think no wise man has ever contradicted him. ...

Section 13—All human constitutions are subject to corruption, and must perish, unless they are timely renewed, and reduced to their first principles: This was chiefly done by means of those tumults which our author ignorantly blames: The whole people by whom the magistracy had been at first created, executed their power in those things which comprehend sovereignty in the highest degree, and brought everyone to acknowledge it: There was nothing that they could not do, who first conferr’d the supreme honours upon the patricians, and then made the plebeians equal to them. Yet their modesty was not less than their power or courage to defend it: and therefore when by the law they might have made a plebeian consul, they did not chuse one in forty years; and when they did make use of their right in advancing men of their own order, they were so prudent, that they cannot be said to have been mistaken in their elections three times, whilst their votes were free: whereas, of all the emperors that came in by usurpation, pretence of blood from those who had usurped, or that were set up by the soldiers, or a few electors, hardly three can be named who deserved that honour, and most of them were such as seemed to be born for plagues to mankind.

Chapter 3:

Section 33—The creature having nothing, and being nothing but what the creator makes him, must owe all to him, and nothing to anyone from whom he has received nothing. Man therefore must be naturally free, unless he be created by another power than we have yet heard of. . . . God only who confers this right upon us, can deprive us of it: and we can no way understand that he does so, unless he had so declared by express revelation, or had set some distinguishing marks of dominion and subjection upon men; and, as an ingenious person not long since said, caused some to be born with crowns upon their heads, and all others with saddles upon their backs.