Historic Document

Cooper Institute Address (1860)

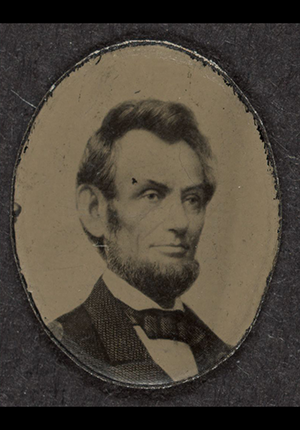

Abraham Lincoln | 1860

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Summary

Arguably the most important speech in American political and constitutional history, Abraham Lincoln delivered this address on February 27, 1860, at the Cooper Institute in New York City. Lincoln’s speech, with its criticism of the Supreme Court’s proslavery decision in Dred Scott, reinvigorated Lincoln’s political prospects and likely secured his nomination as the Republican presidential candidate. This placed Lincoln in the presidency at one of the most critical moments in American history. Unlike his predecessor, James Buchanan, Lincoln refused to accept secession. Instead, he fought a war to save the Union, eventually turning the Union cause towards abolition. His Emancipation Proclamation freed the enslaved behind enemy lines and welcomed black soldiers into the Union army (thereby securing their claim to all the rights of citizenship). Finally, in the weeks before his assassination, Lincoln convinced the House of Representatives to hold a second (and, this time, successful) vote on the proposed Thirteenth Amendment. These ends are glimpsed in this beginning. In his Cooper Union speech, Lincoln embraced Webster’s nationalist theory of the Union, insisted that slavery was wrong, and declared that Congress had both the moral duty and constitutional power to exclude slavery from the territories. By declaring otherwise in Dred Scott, Lincoln insisted, the Supreme Court had made an “obvious mistake.”

Selected by

Laura F. Edwards

Class of 1921 Bicentennial Professor in the History of American Law and Liberty, and Professor of History at Princeton University

Kurt Lash

E. Claiborne Robins Distinguished Professor of Law at the University of Richmond

Document Excerpt

The Court have substantially said, it is your Constitutional right to take slaves into the federal territories, and to hold them there as property. When I say the decision was made in a sort of way, I mean it was made in a divided Court, by a bare majority of the Judges, and they not quite agreeing with one another in the reasons for making it; that it is so made as that its avowed supporters disagree with one another about its meaning, and that it was mainly based upon a mistaken statement of fact—the statement in the opinion that “the right of property in a slave is distinctly and expressly affirmed in the Constitution.”

An inspection of the Constitution will show that the right of property in a slave is not “distinctly and expressly affirmed” in it. Bear in mind, the Judges do not pledge their judicial opinion that such right is impliedly affirmed in the Constitution; but they pledge their veracity that it is “distinctly and expressly” affirmed there—“distinctly,” that is, not mingled with anything else—“expressly,” that is, in words meaning just that, without the aid of any inference, and susceptible of no other meaning.

If they had only pledged their judicial opinion that such right is affirmed in the instrument by implication, it would be open to others to show that neither the word “slave” nor “slavery” is to be found in the Constitution, nor the word “property” even, in any connection with language alluding to the things slave, or slavery; and that wherever in that instrument the slave is alluded to, he is called a “person;”—and wherever his master’s legal right in relation to him is alluded to, it is spoken of as “service or labor which may be due,”—as a debt payable in service or labor. Also, it would be open to show, by contemporaneous history, that this mode of alluding to slaves and slavery, instead of speaking of them, was employed on purpose to exclude from the Constitution the idea that there could be property in man.

To show all this, is easy and certain. When this obvious mistake of the Judges shall be brought to their notice, is it not reasonable to expect that they will withdraw the mistaken statement, and reconsider the conclusion based upon it?