Summary

William Williams was an early critic of British policies who arrived in Philadelphia after independence had been declared. He signed the Declaration on August 2, 1776.

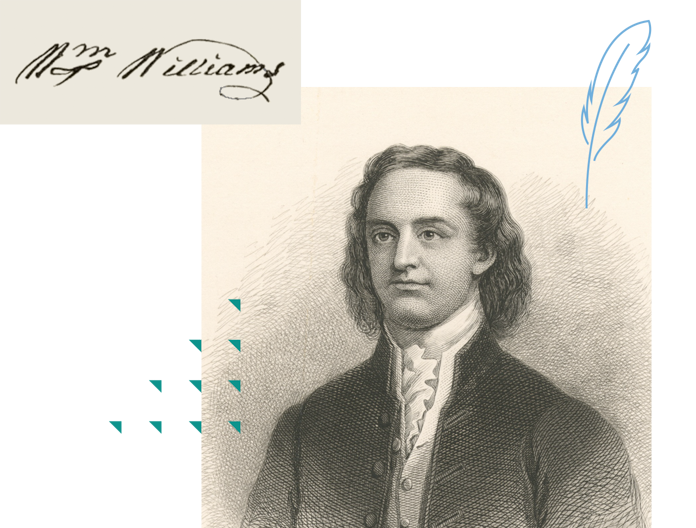

William Williams | Signer of the Declaration of Independence

2:21

Biography

Born in Lebanon, Connecticut, William was the son of the pastor of the First Congregational Church of Lebanon, Solomon Williams, and his wife, Mary Porter Williams. Like his father before him, Williams attended Harvard College where he studied theology and law, intending to follow his father into the ministry. But in 1754 when war between France and England spread to America, he decided to join the militia and fight for Britain. After the British victory in that war, he chose a new path: He opened a store in his hometown. By 1757, he had entered colony-wide politics, serving in the Connecticut House of Representatives from 1757 until 1776, and then again from 1780 to 1784.

Williams was an early critic of British policies and an activist. He joined the Sons of Liberty, supported the non-importation agreements of 1769 and was sorely disappointed when some of Connecticut’s leading merchants began to ignore their commitment to non-importation once most of the Townshend Acts were repealed. His marriage, in 1771, to the daughter of Connecticut’s Governor Jonathan Trumbull, the only royal governor to support independence, reinforced his own growing belief that independence was essential.

On July 1, 1774, only a month after the Coercive Acts were passed, Williams composed a bold and angry letter from “America” to King George III. He published it, using a pseudonym, in the Connecticut Gazette. The piece praised George II who, Williams wrote, had governed the colonies well. Sadly, Williams declared, George III did not. “We only ask that you would govern us upon the same constitutional plan, and with the same justice and moderation that [your father] did, and we will serve you forever. And what is the language of your answer...? Ye Rebels and Traitors...if ye don't yield implicit obedience to all my commands, just and unjust, ye shall be drag'd in chains across the wide ocean, to answer your insolence, and if a mob arises among you to impede my officers in the execution of my orders, I will punish and involve in common ruin whole cities and colonies, with their ten thousand innocents, and ye shan't be heard in your own defense, but shall be murdered and butchered by mydragoonsinto silence and submission. Ye reptiles! ye are scarce intitled [sic] to existence any longer....Your lives, liberties and property are all at the absolute disposal of my parliament."

Williams' strong support of the American cause led to his appointment as a delegate to the Second Continental Congress. Because this appointment came on July 11, 1776, nine days after Connecticut learned that independence had been declared, Williams did not participate in the debate over a break from Britain. He did not arrive in Philadelphia until July 28, but he did sign the Declaration of Independence on August 2 as a representative of his state.

On August 10, 1776, British troops readied to land on Long Island. As a veteran of an earlier war, Williams could only hope, as he told Joseph Trumbull, that the American soldiers “will acquit themselves like Men & be strong in the Day of approaching Conflict.” After the Americans were crushingly defeated at the Battle of Brooklyn, he wrote once again to his in-law: “Our Affairs are truly in a critical Situation, but far I hope from desperate. My trust & hope is in a merciful & just God, who with one Volition of his Will can change their appearance. No means for our defense & Safety must be omitted [sic] &; may God grant Our Officers & soldiers, great Wisdom, Understanding, Courage & Resolution.” But as the American army abandoned New York, he argued that this turn of events signaled “the Displeasure & Anger of almighty God against a sinful People.” His sorrow was palpable, yet it did not remain. He was soon expressing a will to win and a wish that God would “be on our Side & vindicate our righteous Cause agt our most unjust & more than Savage Foes.”

Williams did not remain long at the Congress. By the 13th of November, 1776, he had returned to Connecticut. He was content to leave the national political stage and devote his energies to his home state. Beginning in 1780, he was a member of the Governor’s council. Despite never having passed the bar, he became a judge of the Windham County Court in 1781 and served on that bench until 1804. In 1784, he was made a judge of the Connecticut Supreme Court of Errors.

Although generally well thought of, Williams apparently did receive criticism for resigning his colonelcy in the Connecticut militia when the revolution began. His reputation was restored when, in 1781, following Benedict Arnold’s raid on New London, Williams rode 23 miles in three hours to volunteer to protect the town. He arrived too late; New London was in flames. And that winter, when a French regiment was stationed in Lebanon, he turned over his home to French officers.