Summary

William Samuel Johnson supported the spirit of compromise at the Constitutional Convention and the Constitution’s ratification at Connecticut’s state convention.

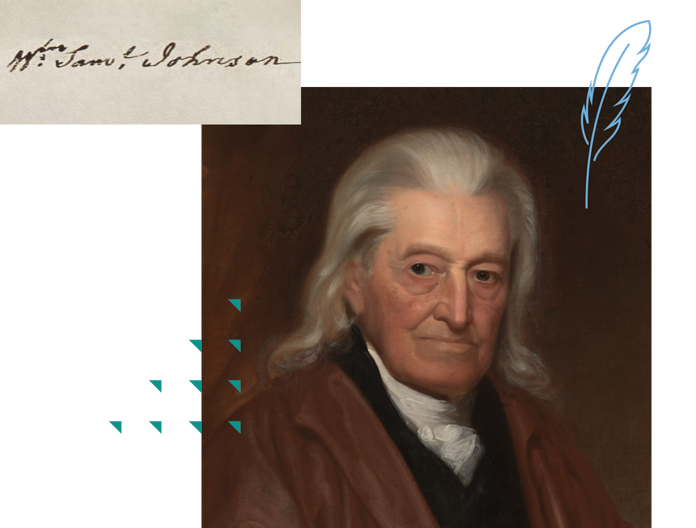

William Samuel Johnson | Signer of the Constitution

3:35

Biography

William Samuel Johnson was born in 1727. His father was a distinguished Anglican minister who was the first president of King’s College [later Columbia University]. William’s father educated him and prepared him to enter Yale College, from which he graduated in 1744 at the age of 17. Within three years, Johnson also received a master’s degree from Yale.

Although his father implored him to follow in his footsteps and become a minister, Johnson preferred to pursue a career as a lawyer. He took charge of his own legal education and passed the Connecticut bar. His practice grew easily, with clients from Connecticut and neighboring New York. His marriage in 1749 to the daughter of a successful businessman solidified Johnson’s place within New England’s elite society.

By the 1750s, Johnson had become a militia officer. Soon afterward, in the early 1760s, he entered politics, serving in the colonial assembly. By 1766, he joined the elite political leaders in the upper house of the legislature. As the tensions between the colonies and Great Britain grew, Johnson’s own divided loyalties surfaced. He participated in the Stamp Act Congress in 1765, but was more an observer than participant in the protest against the Townshend Acts two years later. Although Johnson thought Britain’s new approach to governing the colonies was misguided, he still hesitated to commit to either side for he had friends in England and had received two honorary degrees from Oxford University. Perhaps most importantly, as the son of an Anglican minister, his ties to the Church of England were strong.

Johnson decided to oppose the growing radicalism emerging in New England, pursuing a policy of reconciliation between Mother Country and colonies. He refused a seat in the First Continental Congress. Even after hostilities began, he worked—unsuccessfully—as a peacemaker. When the Connecticut legislature became a stronghold of the pro-independence movement, Johnson was cut off from political officeholding. He was actually arrested as a Loyalist, charged with communicating with the enemy, but was released.

Despite his ambivalence about the Revolution, Johnson returned to politics when the war ended. He served in the newly established Confederation Congress. And, in 1787, he was one of three Connecticut delegates to the Constitutional Convention. William Pierce was clearly impressed with Johnson who he said was “celebrated for his legal knowledge” and his “strong and enlightened understanding.” But Pierce found Johnson’s oratorical skills wanting because, “there is something in the tone of his voice not pleasing to the Ear.” Still, he conceded that Johnson was a well-mannered gentleman who, “engages the Hearts of Men by the sweetness of his temper.”

Johnson arrived in Philadelphia on June 2 and did not miss any sessions that followed. Writing to his son on June 27, he offered his impression of the Convention delegates: “I can only tell you that much information and eloquence has been displayed in the introductory speeches, and that we have hitherto preserved great temperance, candor, and moderation in debate, and evinced much solicitude for the public weal. Yet, as was to be expected, there is great diversity of sentiment, which renders it impossible to determine what will be the result of our deliberations.”

As the Convention progressed, Johnson was clearly pleased with the spirit of compromise that overcame the diversity of sentiments. In particular, he supported the Connecticut Compromise drafted by fellow Connecticut delegate Roger Sherman, and, though he chaired the Committee of Style, he accepted the dominance of that committee by Gouverneur Morris.

When the ratification convention was called in Connecticut, Johnson spoke eloquently in favor of the Constitution, arguing that it would not enforce regulations and command respect by armed force but by “the energy of law; and this force is to operate only upon individuals who fail in their duty to their country. This is the peculiar glory of the Constitution, that it depends upon the mild and equal energy of the magistracy for the execution of the laws.”

After the Constitution was ratified, Johnson served in the first federal Senate. He resigned from the Senate in 1791 when the government moved from New York to Philadelphia, because he preferred to focus his energies on his presidency of New York’s Columbia College. In 1800, he retired from the College. He died in 1819, at the age of 92, in the city of his birth, Stratford, Connecticut.