Summary

William Livingston attended the Constitutional Convention while was also New Jersey’s governor. He supported equal representation of states in the Senate.

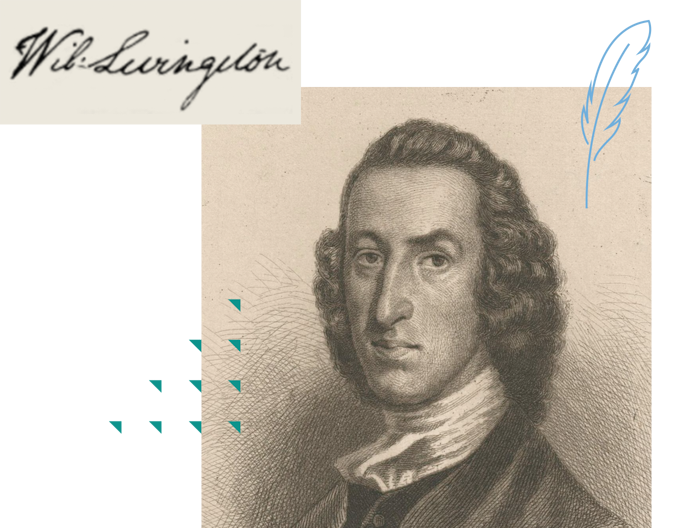

William Livingston | Signer of the Constitution

3:22

Biography

William Livingston was born in 1723 in Albany, New York, the fourth and youngest son of the Lord of Livingston Manor, Philip Livingston and Catherine Van Brugh, the daughter of Albany’s mayor. Livingston, like many sons of the elite, was educated by tutors and then sent to prepare for college with an Anglican minister and a college graduate who lived among the Iroquois Indians. Livingston next attended Yale and graduated in 1741.

His family had hoped that William would engage in commercial pursuits in New York City or enter the fur trade, but he chose the study of law instead. In 1748, now married to the daughter of a prosperous New Jersey landowner, Livingston was admitted to the bar. Politically, he quickly became associated with New York upstate Presbyterian landowners whose “country party” opposed the New York City based “popular party” of Anglicans led by the De Lancey family. With William Smith Jr and John Morin Scott he founded a weekly journal, the Independent Reflector, which served as a platform for their opposition to Anglican control over King’s College [later Columbia University].They saw the founding of the college as a step in the conspiracy by Anglicans to install a bishop in the colonies. By the time his faction took control of the colonial assembly in 1759, Livingston was one of its leaders. His party not only challenged Anglican control of King’s College , but they attacked Parliament’s interference in colonial affairs.

In 1769, Livingston’s party was splintered by the question of how to respond to British taxation and it lost control of the assembly. Soon afterward, in 1772, Livingston abandoned his legal practice and moved to Elizabethtown, New Jersey. There he built a large country home he called Liberty Hall and made plans to live out his days as a gentleman farmer. But the deepening hostility to Britain – what he had always shared – drew him back to the political arena. In 1774, he was chosen to serve in the First Continental Congress and in 1775-76 he served in the Second Continental Congress. He left before the Declaration of Independence was written in order to take command of a New Jersey militia. Before the year was over, he was elected the first governor of the state.

His position as governor put a price on his head, and British sympathizers hoping to collect the reward for his capture as well as British troops could frequently be seen around Liberty Hall. To ensure his family’s safety, he moved them to Parsippany. But his home there was raided in 1779 and his family briefly held captive. Eventually, the family returned to Liberty Hall.

In 1787, Livingston filled a vacancy in the New Jersey delegation to the Constitutional Convention, although his role as governor caused him to miss a number of sessions. William Pierce could not hide his dislike of Livingston, writing that he was “a Man of the first rate talents, but he appears to me rather to indulge a sportiveness of wit, than a strength of thinking…. His writings teem with satyr [sic].” Pierce noted, adding that, for all his education and genius, he was a poor orator. Livingston did, however, serve on a number of important committees, chairing the committee that reached a compromise on African American representation in determining a state’s number of representatives in the House. As the governor of a small state, he supported equal representation in the Senate.

As the convention neared its end, Livingston wrote to New Yorker John Jay on September 4th, joking about the many months it had taken the delegates to shape the new government. Seven days later, a letter to Jay revealed his impatience with the delegates prone to love the sound of their own voices: “My hopes of returning by the time expected,” he declared, “are a little clouded by reason of there being certain creatures in this world that are more pleased with their own speeches than they can prevail upon any body else to be.”

Livingston died in 1790 at the age of 67.